Even if you can name only one ancient Greek, you can name Plato. You can also probably say at least a little about him, if only some of the things humanity has known since antiquity. Until recently, of course, that qualification would have been redundant. But now, thanks to an ongoing high-tech push to read heretofore inaccessible ancient documents, we’re witnessing the emergence of new knowledge about that most famous of all Greek philosophers — or at least one of the most famous Greek philosophers, matched in renown only by his teacher Socrates and his student Aristotle.

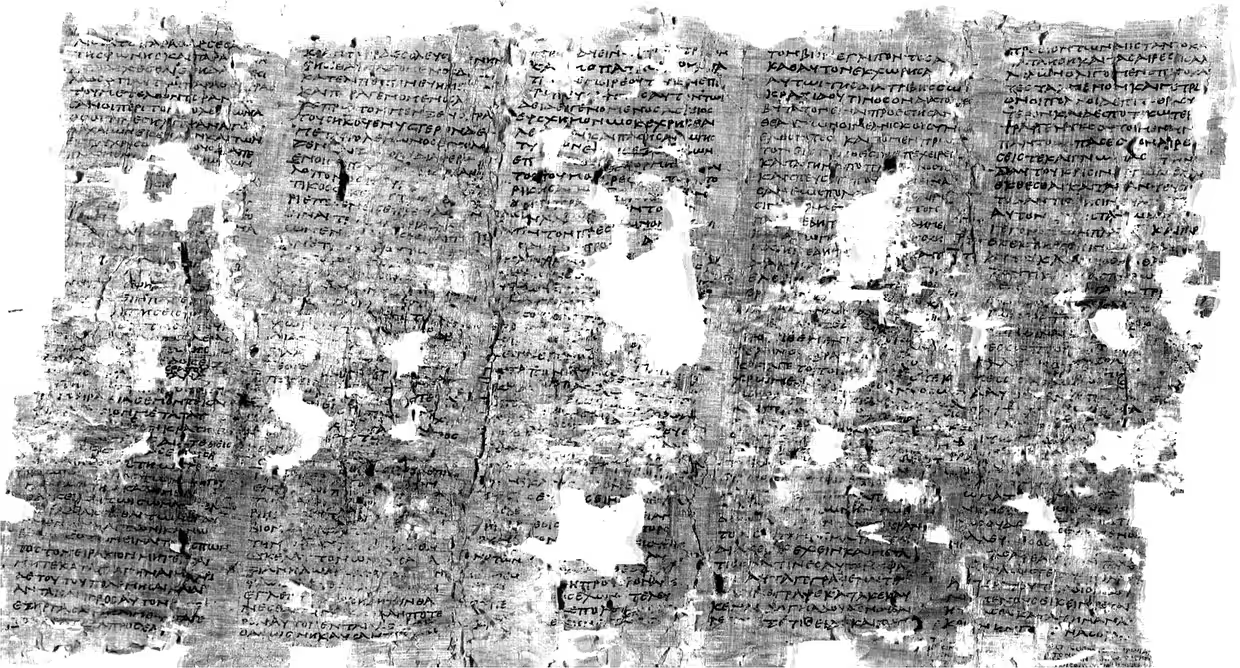

Up until now, we’ve only had a general idea of where Plato was interred after his death in 348 BC. But “thanks to an ancient text and specialized scanning technology,” writes Smithsonian.com’s Sonja Anderson, “researchers say they have solved the mystery of Plato’s burial place: The Greek philosopher was interred in the garden of his Athens academy, where he once tutored a young Aristotle.” This location was recorded about two millennia ago “on a papyrus scroll housed in the Roman city of Herculaneum,” which was entombed along with Pompeii by the explosion of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Like much else in those cities, this scroll was preserved for centuries under layers of ash. It was just one of many scrolls discovered in a villa, which may have belonged to Julius Caesar’s father-in-law, back in 1750. But for long thereafter, those scrolls were more or less unreadable, having been so thoroughly charred by the explosion of Mount Vesuvius that they crumbled to dust at any attempt to unroll them. But “recent breakthroughs have allowed researchers to read the fragile texts without touching them”: witness the projects involving particle accelerators and artificial intelligence previously featured here on Open Culture.

The research project that has deciphered part of this scroll, a text by the philosopher Philodemus called the History of the Academy — that is, Plato’s academy in Athens — is led by University of Pisa professor of papyrology Graziano Ranocchia. Using a “bionic eye” technique involving infrared and X‑ray scanners, he and his team have also discovered evidence that Plato didn’t much like the music played at his deathbed by a Thracian slave girl. “Despite battling a fever and being on the brink of death,” writes the Guardian’s Lorenzo Tondo, he “retained enough lucidity to critique the musician for her lack of rhythm.” Even if you know little about Plato, you’re probably not surprised to hear that he was pointing out the difference between the real and the ideal up until the very end.

Related content:

Researchers Use AI to Decode the First Word on an Ancient Scroll Burned by Vesuvius

Orson Welles Narrates an Animation of Plato’s Cave Allegory

Plato’s Dialogue Gorgias Gets Adapted into a Short Avant-Garde Film

How 99% of Ancient Literature Was Lost

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.