The connections we make between various philosophers and philosophical schools are often connections that have already been made for us by teachers and scholars on our paths through higher education. Many of us who have taken a philosophy class or two leave it at that, content we’ve got the gist of things and that specialists can parse the details perfectly well without us. But there are those curious people who continue to read abstruse and difficult philosophy after their intro classes are over, for the sheer, perverse joy of it, or from a burning desire to understand truth, beauty, justice, or whatever.

And then there are those who embark on a thorough self-guided tour of Western philosophical history, attempting, without the aid of university departments and faddish interpretive schemes, to weave the disparate strains of thought together. One such autodidact and academic outsider, designer Deniz Cem Önduygu of Istanbul, has combined an encyclopedic mind with a talent for rigorous outline organization to produce an interactive timeline of the history of philosophical ideas. It is “a purely personal project,” he writes, “that I’m doing in my own time, with my limited knowledge, for myself.”

Önduygu shares the project not to show off his learning but, more humbly, to “get feedback and to make it accessible to those who are interested.” It may be precious few people who have both the time and inclination to teach themselves the history of philosophy, but if you are one of them, this incredibly dense infographic is as good a place to start as any, and while it may appear intimidating at first glance, its menu in the upper right corner allows users to zero in on specific thinkers and schools, and to confine themselves to smaller, more manageable areas of the whole.

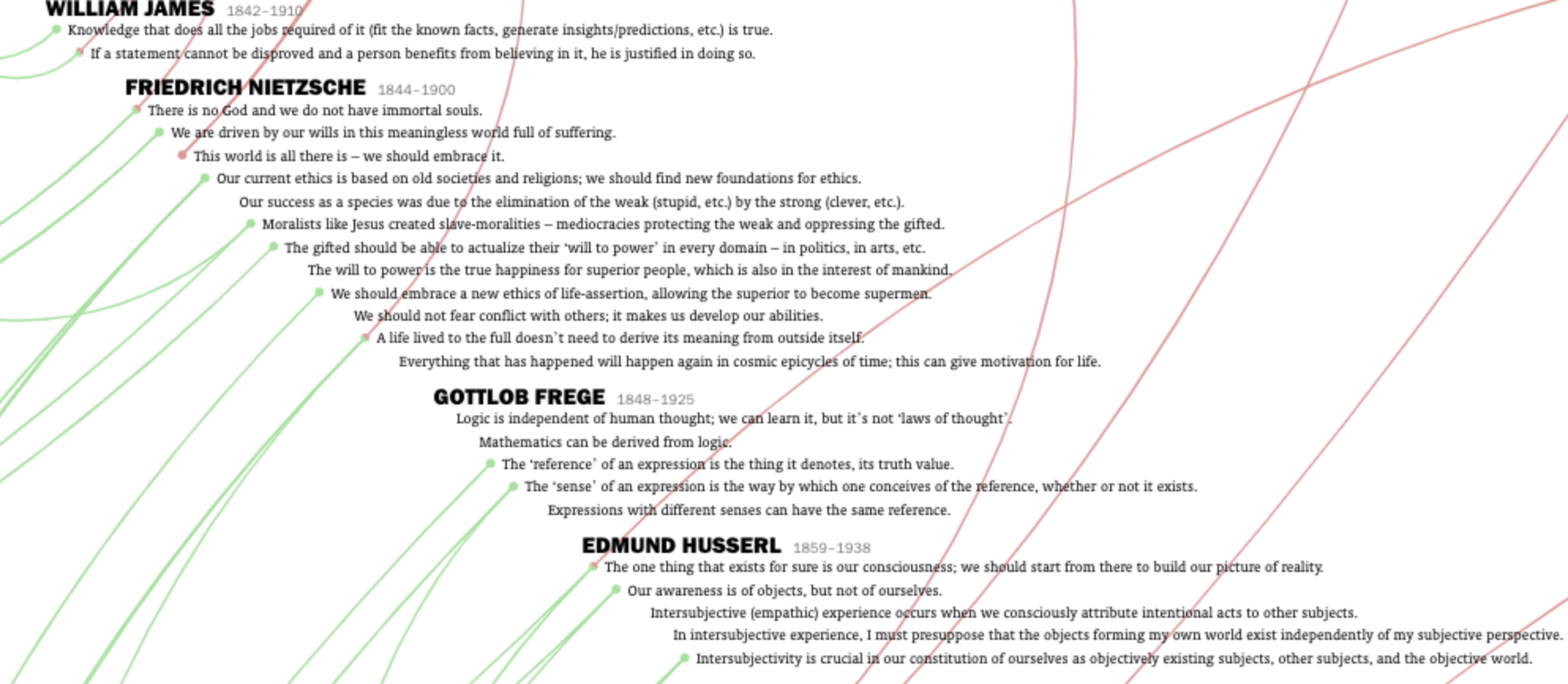

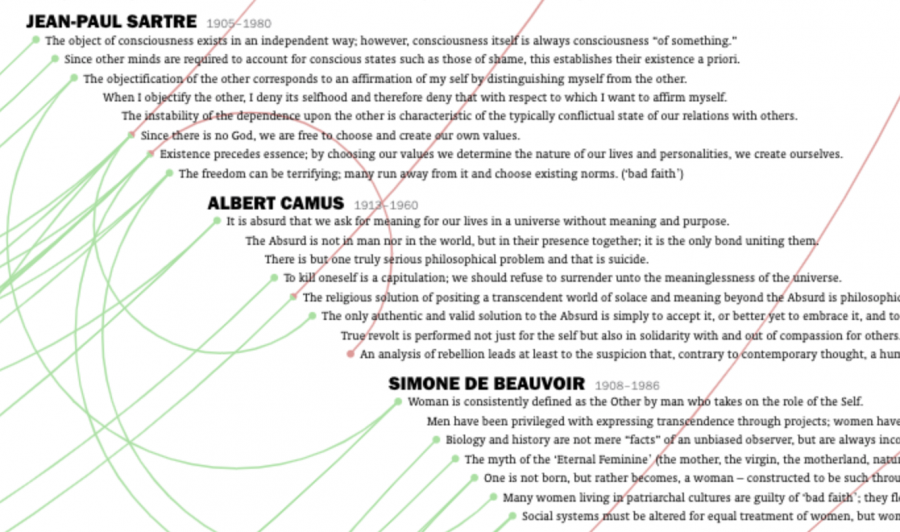

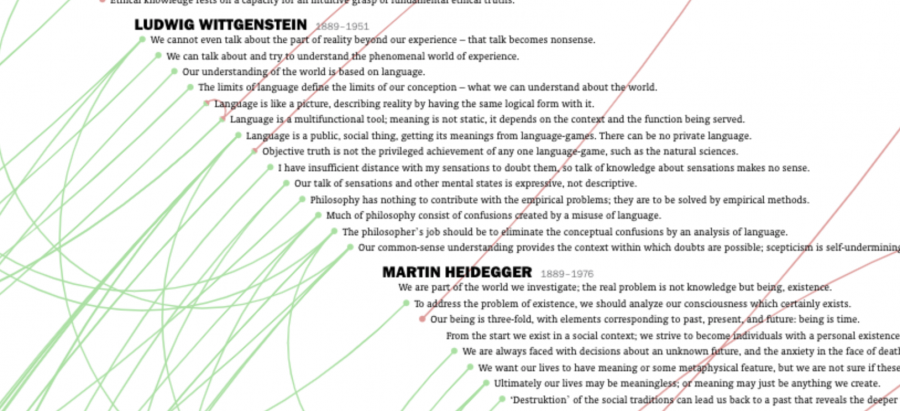

As for the timeline itself, “viewers can zoom in and out,” notes Daily Nous, “and see philosophers listed in chronological order, with ideas they’re associated with listed beneath them. These ideas, in turn, are connected by green lines to similar or supporting ideas elsewhere on the timeline, and connected by red lines to opposing or refuting ideas elsewhere on the timeline. If you hover your mouse cursor over a single idea, all but it and its connected ideas fade. You can then click on the idea to bring those connected ideas closer for ease of viewing.”

The designer admits this is a “never-ending work in progress” and mainly a source for reminding himself of the main arguments of the philosophers he’s surveyed. The major sources for his timeline are “Bryan Magee’s The Story of Philosophy and Thomas Baldwin’s Contemporary Philosophy, along with other works for specific philosophers and ideas.” But many of the connections Önduygu draws in this extensive web of green and red are his own.

He explains his rationale here, noting, “The lines here do not always depict a direct transfer between two people; I think of them as tracing the development of an idea throughout time within our collective conception.” Spend some more time with this impressive project at the History of Philosophy Summarized & Visualized (the site works best in Chrome), and feel free to get in touch with its creator with constructive criticism. He welcomes feedback and is open to opposing ideas, as every lifelong learner should be.

via Daily Nous

Related Content:

150+ Free Online Philosophy Courses

The History of Philosophy Visualized

A History of Philosophy in 81 Video Lectures: From Ancient Greece to Modern Times

The History of Philosophy … Without Any Gaps

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness