During the Great Depression, The Farm Security Administration—Office of War Information (FSA-OWI) hired photographers to travel across America to document the poverty that gripped the nation, hoping to build support for New Deal programs being championed by F.D.R.‘s administration.

Legendary photographers like Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Arthur Rothstein took part in what amounted to the largest photography project ever sponsored by the federal government. All told, 170,000 photographs were taken, then catalogued back in Washington DC. The Library of Congress became their eventual resting place.

We first mentioned this historic project back in 2012, when the New York Public Library put a relatively small sampling of these images online. But now we have bigger news.

Yale University has launched Photogrammar, a sophisticated web-based platform for organizing, searching, and visualizing these 170,000 historic photographs.

The Photogrammar platform gives you the ability to search through the images by photographer. Do a search for Dorothea Lange’s photographs, and you get over 3200 images, including the now iconic photograph at the bottom of this post.

Photogrammar also offers a handy interactive map that lets you gather geographical information about 90,000 photographs in the collection.

And then there’s a section called Photogrammar Labs where innovative visualization techniques and data experiments will gradually shed new light on the image archive.

According to Yale, the Photogrammar project was funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). Directed by Laura Wexler, the project was undertaken by Yale’’s Public Humanities Program and its Photographic Memory Workshop.

Top image: A migrant agricultural worker in Marysville migrant camp, trying to figure out his year’s earnings. Taken in California in 1935 by Dorothea Lange.

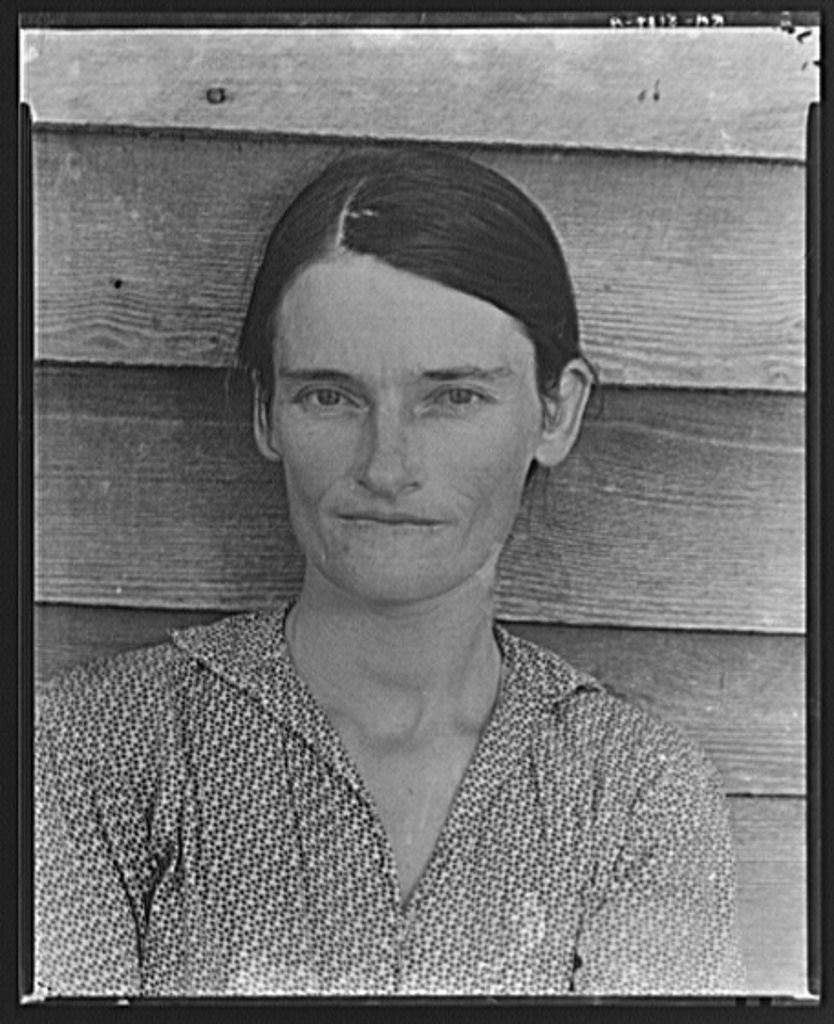

Second image: Allie Mae Burroughs, wife of cotton sharecropper. Photo taken in Hale County, Alabama in 1935 by Walker Evans.

Third image: Wife and children of sharecropper in Washington County, Arkansas. By Arthur Rothstein. 1935.

Fourth image: Wife of Negro sharecropper, Lee County, Mississippi. Again taken by Arthur Rothstein in 1935.

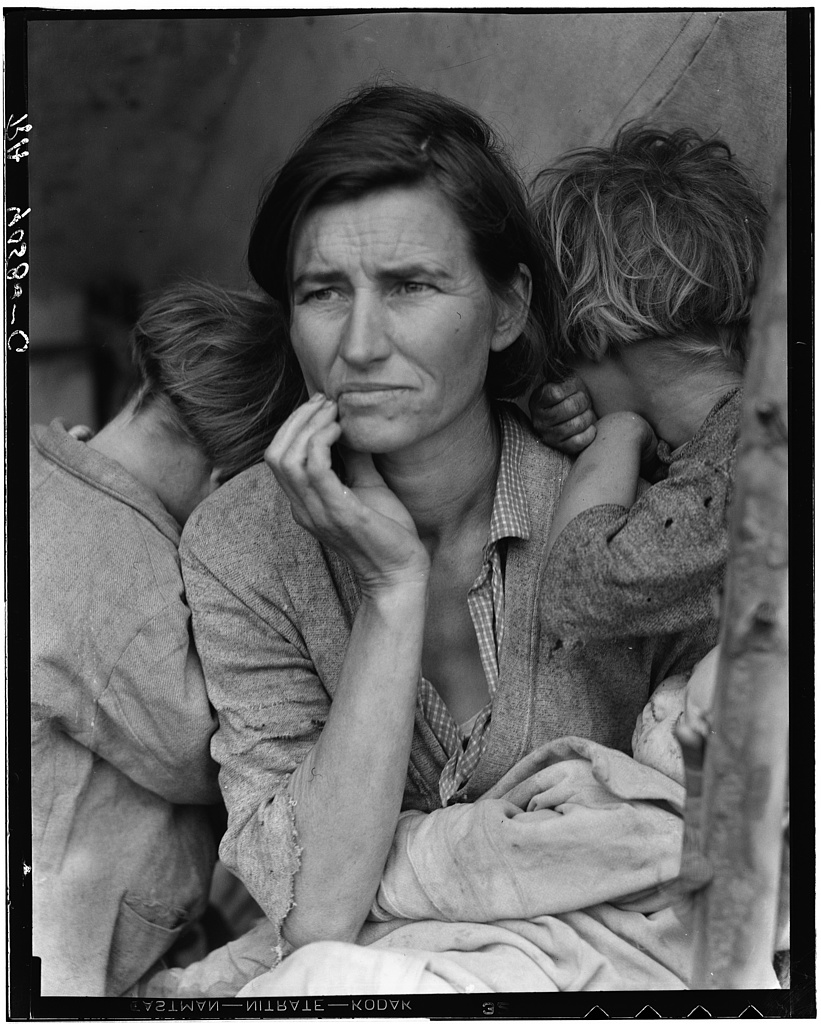

Bottom image: Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Taken by Dorothea Lange in Nipomo, California, 1936.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2014.

Related Content:

Harvard Puts Online a Huge Collection of Bauhaus Art Objects

Download for Free 2.6 Million Images from Books Published Over Last 500 Years on Flickr

130,000 Photographs by Andy Warhol Are Now Available Online, Courtesy of Stanford University

The Medieval Masterpiece, the Book of Kells, Is Now Digitized & Put Online