From the time my daughter was born, my wife and I took her out to restaurants—not to annoy the other diners, mind you, she was usually very well behaved—but to expose her palate to as much variety as possible and socialize her early to new and unfamiliar environments. At one establishment, during her second year, another toddler her age approached us, her mother trailing behind. “Can we say hi?” the mother asked. We said, “of course.” “What languages does your child speak?” the woman politely inquired.

We looked at each other, a little chagrined. Parents of young children often play subtle games of one-upsmanship, whether they mean to or not, and most parents fret over whether they’re offering their kids the richest learning experiences they can.

At that moment we felt slightly inadequate. “She just knows the one language,” we mumbled, turning back to our menus after a few more pleasantries. I may have studied Latin for several years, learned to read a little French and Italian and speak enough Spanish for some halting small talk, but for all intents and purposes, we’re a monolingual household.

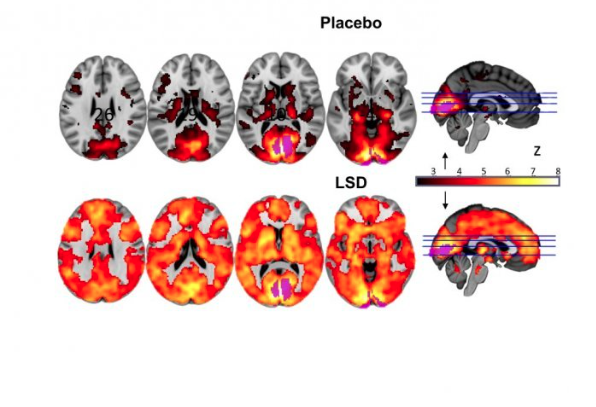

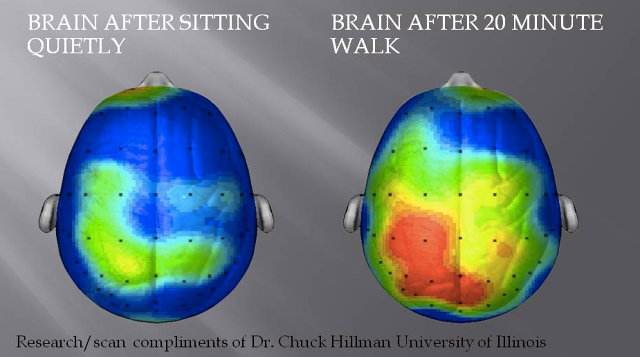

And according to current research on infant brain development, this may put our poor preschooler at a disadvantage to children who can greet her in two or more tongues. That’s not only because those children will grow up able to easily conduct business across countries and continents, but also because, Big Think reports, “a new study shows that babies raised in bilingual environments develop more cognitive skills like decision-making and problem-solving—before they can even speak.” The brains of bilingual (and trilingual, etc.) people “look and act differently,” the TED-Ed video at the top of the post claims, than those of the monolingual. (The New York Times puts things more bluntly: “Being bilingual, it turns out, makes you smarter.”)

Is this really so? Princeton University neuroscientist Sam Wang explains why it may be in the short Big Think video further up. Wang and other researchers have acquired their findings by conducting research on some of the most adorable scientific subjects ever. One study, conducted at the University of Washington, tested 16 babies—half from only English-speaking families and half from English- and Spanish-speaking households. As you can see in the video clip above, the tots were monitored via a magnetoencephalographic helmet designed specially for babies, as they listened to sounds specific to one or both languages.

Lead author of the study Naja Ferjan Ramirez writes, “results suggest that before they even start talking, babies raised in bilingual households are getting practice at tasks related to executive function.” Her co-author Patricia Kuhl elaborates:

Babies raised listening to two languages seem to stay ‘open’ to the sounds of novel languages longer than their monolingual peers, which is a good and highly adaptive thing for their brains to do.

The University of Washington researchers are but one team among several dozen who have drawn these kinds of conclusions about the benefits of growing up bilingual. Both The New York Times and The New Yorker survey and link to much of this research. The New Yorker also profiles a skeptical study by psychologist Angela de Bruin that undercuts some of the enthusiasm and possible overstatement of the benefits of bilingualism; and yet her research doesn’t deny that they exist. Whatever their degree, the question might arise for anxious parents like myself: Is there anything we can do to help our monolingual children catch up?

Never fear, they can still profit from exposure to other languages, though you may not speak them fluently at home. Big Think offers a couple pointers for raising a bilingual child, even if you’re not bilingual yourself.

Lots of foreign words make their way into English. You can point out foreign foods every time you have them, or watch a bilingual show with your child. As long as you expose them to the foreign words in a consistent way with the same context, they’ll reap the benefits.

Try using a Language Exchange community, where you and your child can speak another language with native speakers together. You’ll both reap the benefits with constant practice.

Every little bit of exposure helps, and no amount of language training will ever do any harm. “Basically,” writes Big Think, “there is no downside to being bilingual.” The earlier we start, the better, but there’s no reason not to engage with other languages at any age. We can help you do that here with our expansive collection of lessons in 48 languages. And to learn even more about bilingualism and its prevalence amidst rapidly changing demographics in the U.S. and around the world, see the University of Illinois Spanish linguistics professor Kim Potowski’s TEDx talk below, “No Child Left Monolingual.”

via Big Think

Related Content:

Learn 48 Languages Online for Free: Spanish, Chinese, English & More

Learn Latin, Old English, Sanskrit, Classical Greek & Other Ancient Languages in 10 Lessons

200 Free Kids Educational Resources: Video Lessons, Apps, Books, Websites & More

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness