Experience long ago conferred the mantle of authority on broadcaster, biologist, natural historian and author David Attenborough, age 97.

In his late 20s, he landed at the BBC, producing live studio broadcasts that ran the gamut from children’s shows, ballet performances and archeological quizzes to programs focused on cooking, religion and politics.

When an educational show starring animals from the London Zoo became a hit with viewers, the powers that be built on its popularity with a fresh take — a show that sent the intrepid young Attenborough around the world, seeking animals in their native habitats. He was accompanied by cameraman Charles Lagus and two zoologists, whom he quickly supplanted as host.

It made for thrilling viewing in an era when wildlife tourism was available to a very few.

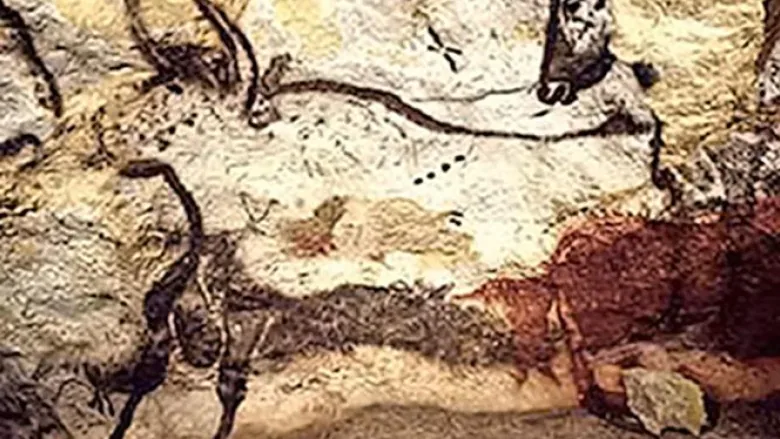

The New York Times notes that many of the creatures who cropped up onscreen in these early Zoo Quest episodes were shipped back to London Zoo:

It is not the kind of mission we approve of nowadays, but without it the West might never have gotten interested in wildlife to begin with. We started by shooting exotic species for their skins and bones and trapping them for our zoos, and only recently moved to worrying about their survival in the wild and the health of the planet in general. This history is symbolized by the transformation of Attenborough himself from a talking and writing crocodile hunter to the greatest living advocate of the global ecosystem.

In Borneo in 1956, in search for Komodo dragons, he paused for an encounter with an orangutan, above, and also a big whiff of durian, the spiky, odiferous fruit whose aroma famously got it banned from Singapore’s elegant Raffles Hotel, with taxis, planes, subways, and ferries following suit.

Soon thereafter, the six-episode hunt for the Komodo dragon finds Attenborough in Java, masking his nerves as he uses a cutlass, a willingness to climb trees, and a cloth sack to get the better of a fully grown python.

(Once the serpent was settled at the London Zoo, he made the trek to the BBC for an in-studio appearance.)

You’ll note that this episode is in color.

Although Zoo Quest filmed in color, it aired ten years before color broadcasts were available to UK viewers, so most of the folks watching at home assumed it had been shot in black and white.

In 1960, Attenborough used the latest — now severely outmoded-looking– technology to capture the first audio recording of the indri, Madagascar’s largest lemur for Attenborough’s Wonder of Song.

This audio victory led him to wonder if he could be the first to film an indri.

Frustrated by the thick canopy overhead, Attenborough resorted to playback, successfully tempting the animals to not only come closer, but do so while vocalizing.

Mating calls?

No. Attenborough deduced that they were the indris’ “battle songs”, issued as a warning to the perceived threat of unfamiliar indris.

In 2011, Attenborough returned to Madagascar, listening respectfully to Joseph, a local hunter turned conservationist, who explains how the local populace no longer think of indri as a food source, but rather a symbol of their commitment to preserving the natural world around them. Joseph’s relationship with the indri affords Sir David a rare opportunity, as the indri feed from his hand:

Fifty years ago, I spent days and days and days searching through the forest, with these firing their noise overhead but now this group is so accustomed to seeing people around that I have been right close up to them, something I never believed could have be possible.

Read more about David Attenborough’s Zoo Quest experiences in his memoir, Adventures of a Young Naturalist, and watch a playlist of documentaries for the BBC here.

Related Content

David Attenborough Reads “What a Wonderful World” in a Moving Video

Björk and Sir David Attenborough Team Up in a New Documentary About Music and Technology

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.