Let’s provide the context, just like host Adam Neely and guest Brian Krock do in this video: in 1960 Steve Lacy, a young, white soprano sax player, briefly joined Thelonious Monk’s band. Two years previous, Lacy had been the first jazz musician to release an album of Monk’s compositions other than the man himself. Even so, Lacy was young, excited, and starstruck at playing alongside not just Monk but John Coltrane (who shared the bill on the 16 week tour), just absorbing everything.

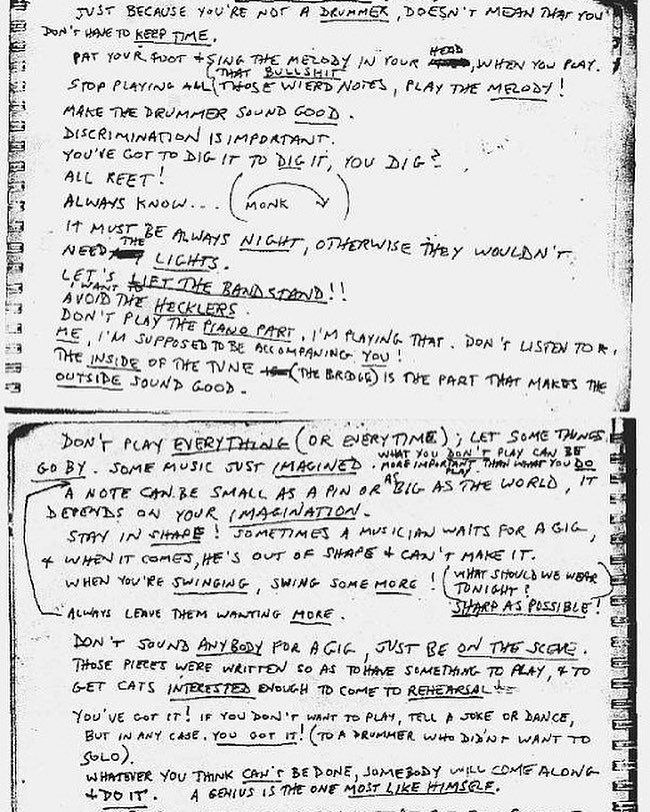

At some point, Monk took Lacy aside and gave his some advice which Lacy wrote down, 25 pieces of advice to be exact.

In the video below, from Neely’s always interesting channel (we’ve previously written about him here), he and Krock go through the 25 points and comment on each one. For those who love to hear musicians (or any artist) talk shop, this is wonderful stuff.

Some of the advice is such as befits a live musician—“Pat your foot & sing the melody in your head, when you play”, “Don’t play the piano part, I’m playing that”, “When you’re swinging, swing some more!,” and “A note can be small as a pin or as big as the world, it depends on your imagination.”

Others are more crucial to the business, especially “Don’t sound anybody for a gig, just be on the scene.” That is: if you around the scene enough, and show your worth, you will get asked to play. But just cold asking won’t get you anywhere. Also, when asked what to wear to a gig, Monk advises: “Sharp as possible!” which you could indeed say of Monk.

Other advice is more mystical: “You’ve got to dig it to dig it, you dig?” “What you don’t play can be more important than what you do.”

And the one that gets quoted the most, “A genius is the one most like himself.” That’s true when it comes to Monk or any of the giants of jazz. To hear Monk, or Coltrane, or Miles Davis play is to hear the artist, the genius, and the person, not just the melody or the instrument. It reminds me of the great Harry Partch quote: “The creative person shows himself naked. And the more vigorous his creative act, the more naked he appears — sometimes totally vulnerable, yet always invulnerable in the sense of his own integrity.”

And maybe that’s why we keep coming back to them, long after their physical bodies have left this plane of existence.

The full list is as follows:

- Just because you’re not a drummer, doesn’t mean you don’t have to keep time.

- Pat your foot & sing the melody in your head, when you play.

- Stop playing all that bullshit, those weird notes, play the melody!

- Make the drummer sound good.

- Discrimination is important.

- You’ve got to dig it to dig it, you dig?

- All reet!

- Always know… (monk )

- It must be always night, otherwise they wouldn’t need the lights.

- Let’s lift the band stand!!

- I want to avoid the hecklers.

- Don’t play the piano part, I’m playing that.

- Don’t listen to me. I’m supposed to be accompanying you!

- The inside of the tune (the bridge) is the part that makes the outside sound good.

- Don’t play everything (or every time); let some things go by. Some music just imagined. What you don’t play can be more important than what you do.

- Always leave them wanting more.

- A note can be small as a pin or as big as the world, it depends on your imagination.

- Stay in shape! Sometimes a musician waits for a gig, & when it comes, he’s out of shape & can’t make it.

- When you’re swinging, swing some more!

- (What should we wear tonight?) Sharp as possible!

- Don’t sound anybody for a gig, just be on the scene.

- These pieces were written so as to have something to play, & to get cats interested enough to come to rehearsal.

- You’ve got it! If you don’t want to play, tell a joke or dance, but in any case, you got it! (to a drummer who didn’t want to solo).

- Whatever you think can’t be done, somebody will come along & do it. A genius is the one most like himself.

- They tried to get me to hate white people, but someone would always come along & spoil it.

Related Content:

Thelonious Monk Bombs in Paris in 1954, Then Makes a Triumphant Return in 1969

Andy Warhol Creates Album Covers for Jazz Legends Thelonious Monk, Count Basie & Kenny Burrell

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here.