Before it set itself on fire, HBO’s Game of Thrones resonated deeply with contemporary morality, becoming the most meme-worthy of shows, for good or ill, online. Few scenes in the show’s run — perhaps not even the Red Wedding or the nauseating finale — elicited as much gut-level reaction as Cersei Lannister’s naked walk of shame in the Season 5 finale, a scene all the more resonant as it happened to be based on real events.

In 1483, one of King Edward IV’s many mistresses, Jane Shore, was marched through London’s streets by his brother Richard III, “while crowds of people watched, yelling and shaming her. She wasn’t totally naked,” notes Mental Floss, “but by the standards of the day, she might as well have been,” wearing nothing but a kirtle, a “thin shift of linen meant to be worn only as an undergarment.”

What are the standards of our day? And what is the punishment for violating them? Sarah Brand seemed to be asking these questions when she posted “Red Dress,” a music video showcasing her less than stellar singing talents inside Oxford’s North Gate Church. In less than a month, the video has garnered well over half a million views, “impressive for a musician with hardly any social media footprint or fan base,” Kate Fowler writes at Newsweek.

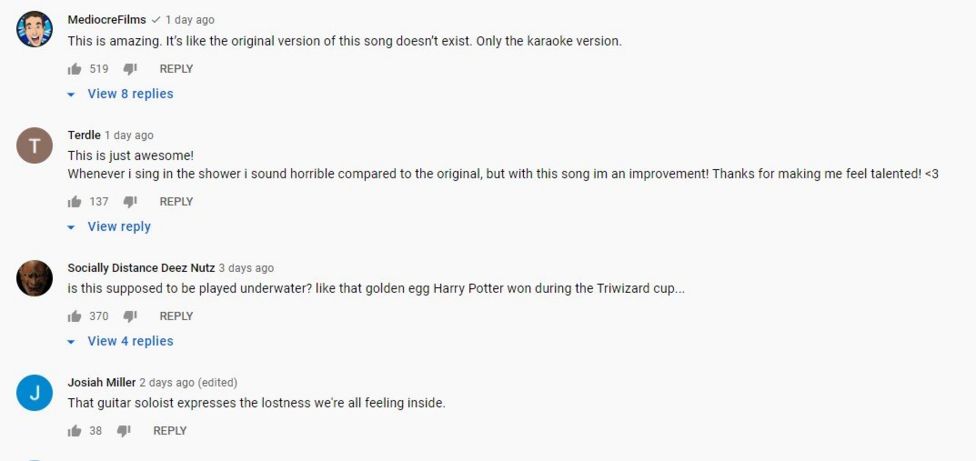

“It takes only a few seconds,” Fowler generously remarks, “to realize that Brand may not have the voice of an angel.” Or, as one clever commenter put it, “She is actually hitting all the notes… only of other songs. And at random.” Is she ludicrously un-self-aware, an heiress with delusions of grandeur, a sad casualty of celebrity culture, forcing herself into a role that doesn’t fit? Or does she know exactly what she’s doing…

The judgments of medieval mobs have nothing on the internet, Brand suggests. “Red Dress” presents what she calls “a cinematic, holistic portrayal of judgment,” one that includes internet shaming in its calculations. Given the amount of online rancor and ridicule her video provoked, it “did what it set out to do,” she tells the BBC. And given that Brand is currently completing a master’s degree in sociology at Oxford University, many wonder if the project is a sociological experiment for credit. She isn’t saying.

Jane Shore’s walk ended with years locked in prison. Brand offered herself up for the scorn and hatred of the mobs. No one is pointing a pike at her back. She paid for the privilege of having people laugh at her, and she’s especially enjoying “some very, very witty comments” (like those above). She’s also very much aware that she is “no professional singer.”

The style in which I sing the song was important because it reflected the story. The vocals don’t seem to quite fit, they seem out of place and they make people uncomfortable… and the video is this outsider doing things differently and causing discomfort and eliciting all this judgement.

All of this is voluntary performance art, in a sense, though Brand has shown previous aspirations on social media to become a singer, and perhaps faced similar ridicule involuntarily. “Part of what this project deals with,” she says, is judgment “overall as a central theme.” She credits herself as the director, producer, choreographer, and editor and made every creative decision, to the bemusement of the actors, crew, and studio musicians. Yet choosing to endure the gauntlet does not make the gauntlet less real, she suggests.

The shame rained down on Shore was part misogyny, part pent-up rage over injustice directed at a hated better. When anyone can pretend (or pretend to pretend) to be a celebrity with a few hundred bucks for cinematography and audio production, the boundaries between our “betters” and ourselves get fuzzy. When young women are expected to become brands, to live up to celebrity levels of online polish for social recognition, self-expression, or employment, the lines between choice and compulsion blur. With whom do we identify in scenes of public shaming?

Brand is coy in her summation. “Judgmental behavior does hurt the world,” she says, “and that is what I’m trying to bring to light with this project.” Judge for yourself in the video above and the … interesting… lyrics to “Red Dress” below.

Came to church to praise all love

Sitting, coming for someone else

It didn’t stew well for me

But I said it was a lover’s deedDidn’t trust my own feels

Let someone else behind my wheel

Said it was love driving me

But the only one who should steer is meCuz what they saw

They see me in a red dress

Hopping on the devil fest

Thinking of lust

As they judge in disgust

What are you doing here?They see me in a red dress

Hopping on the devil fest

Thinking of lust

As I judge in disgust

What am I doing here?Lettin’ someone else steer

I saw a love, precious and fine

Thought I should do anything for time

Time to change the hearts and minds

Of people not like me in break or strideShouldn’t be me, trying to change

Thought I’d be something if I remained

It just ain’t me singing of sins

Watching exclusion getting its winsCuz what they saw

They see me in a red dress

Hopping on the devil fest

Thinking of lust

As they judge in disgust

What are you doing here?They see me in a red dress

Hopping on the devil fest

Thinking of lust

As I judge in disgust

What am I doing here?Lettin’ someone else steer

Came to church

To praise love

Coming for

Someone elseBut all the eyes

Judging in disguise

They don’t see me

Just the liesThey see me in a red dress

No different from the rest

Starting to trust

As they join in a rush

What are we doing here?They see me in a red dress

No different from the rest

Starting to trust

As I lose my disgust

What am I doing here?Striking the fear

They see me in a red dress

Related Content:

Hear the Experimental Music of the Dada Movement: Avant-Garde Sounds from a Century Ago

Brian Eno Explains the Loss of Humanity in Modern Music

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness