Oh, to be in the studio audience of CBS’ Television City in Hollywood on September 9th, 1956, to see Elvis Presley’s gyrating pelvis rocket him to superstardom on The Ed Sullivan Show.

His appearance made television history, but 60 million home viewers were left to fill in some major blanks, as the rising heartthrob was filmed from the waist up whenever he was in motion.

Sullivan had been hesitant to book Elvis, not wanting to court the outrage the magnetic young singer had sparked in two “suggestive” appearances on The Milton Berle Show earlier that year. Elvis, he told the press, was “not my cup of tea” and “wasn’t fit for family entertainment.”

Television host Steve Allen, presumably alert to similar red flags, attempted to skirt the issue by shoehorning Elvis into tie and tails to perform “Hound Dog” to an inattentive, top-hatted basset hound.

Elvis was displeased by this jokey spin, but submitted, and newcomer Allen’s ratings clobbered Sullivan’s that week.

Sullivan sent Steve Allen a telegram:

Steven Presley Allen, NBC TV, New York City. Stinker. Love and kisses. Ed Sullivan.

Whether Sullivan was throwing down a gauntlet, or delivering congratulations with a side of poor sportsmanship is somewhat unclear, but Sullivan was now ready to claim his stake, at ten times the price.

The $5,000 appearance fee that had been floated prior to Elvis’ appearance on The Milton Berle Show, had ballooned to the jaw dropping sum of $50,000 for 3 episodes.

Sullivan and Presley’s names are forever linked for that historic first appearance, but injuries from a car crash knocked the host out of commission. Actor Charles Laughton subbed in as host from Sullivan’s New York studio, and was charged with ushering in Elvis’s remote appearance in a very particular way.

As cultural critic Greil Marcus writes:

Presley was the headliner, and a Sullivan headliner normally opened the show, but Sullivan was burying him. Laughton had to make the moment invisible: to act as if nobody was actually waiting for anything. He did it instantly, with complete command, with the sort of television presence that some have and some — Steve Allen, or Ed Sullivan himself — don’t. It’s a sense of ease, a querulous interrogation of the medium itself, affirming one’s own odd, irreducible subjectivity against the objectivity enforced by any system of representations: that is, getting it across that at any moment that you might forget where you are and say whatever comes into your head, which was exactly what half the country hoped and half the country feared might be the case with Elvis Presley.

Laughton, who elsewhere in the show used a reading of James Thurber’s Red Riding Hood parody, “The Little Girl and the Wolf” to insinuate that “it’s not so easy to fool little girls nowadays as it used to be,” settled on a non-committal “and now, away to Hollywood to meet Elvis Presley!”

Elvis, clad in a non-threatening plaid jacket on a set trimmed with guitar-shaped cut outs, thanked Laughton, and wiped his brow:

Wow. This is probably the greatest honor I’ve ever had in my life. Ah. There’s not much I can say except, it really makes you feel good. We want to thank you from the bottom of our heart.

His first number, “Don’t Be Cruel,” had an immediate effect on the teenage girls in attendance, who knew what they were seeing.

“Thank you, ladies,” he said, coyly acknowledging what all knew to be true, before going on to debut the title song of the motion picture he was in town to film, Love Me Tender, his first of 31 such vehicles.

Disc jockeys tuned in to tape the unreleased song for play on their radio shows, shooting pre-sales up to nearly a million.

Later in the show Elvis returned to cover Little Richard’s hit, “Ready Teddy,” and wish the show’s regular host a swift recovery. And then:

As a great philosopher once said…’You ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog!’

Cue screams.

A week later, The New York Times’ Jack Gould alleged that in booking Elvis, Sullivan had failed to “exercise good sense and display responsibility,” moralizing that “in some ways it was perhaps the most unpleasant of (the singer’s) recent three performances:

Mr. Presley initially disturbed adult viewers — and instantly became a martyr in the eyes of his teen- age following — for his striptease behavior on last spring’s Milton Berle program. Then with Steve Allen he was much more sedate. On the Sullivan program he injected movements of the tongue and indulged in wordless singing that were singularly distasteful.

At least some parents are puzzled or confused by Presley’s almost hypnotic power; others are concerned; perhaps most are a shade disgusted and content to permit the Presley fad to play itself out.

Neither criticism of Presley nor of the teen-agers who admire him is particularly to the point. Presley has fallen into a fortune with a routine that in one form or another has always existed on the fringe of show business; in his gyrating figure and suggestive gestures the teen-agers have found something that for the moment seems exciting or important.

Cue more screams.

A month and a half after his first Sullivan Show booking, Elvis and Sullivan met in the New York studio for a follow up, along with a chaste youth choir, the Little Gaelic Singers, and ventriloquist Señor Wences. (S’alright? S’alright.)

“Don’t Be Cruel,” “Love Me Tender,” and “Hound Dog” were on the menu again, along with a brand new release — “Love Me,” above.

Señor Wences was not the tough act to follow here.

The appearance resulted in more wildly high ratings for Sullivan, and a growing awareness of the perils of rock n’ roll, as embodied by Elvis’ well lubricated nether regions, which the camera, fooling no one, again shied from at crucial moments.

Cue another million teenage fan club enrollments, as well as parents, clergy and other concerned citizens who came together to burn the singer in effigy in Nashville and St. Louis.

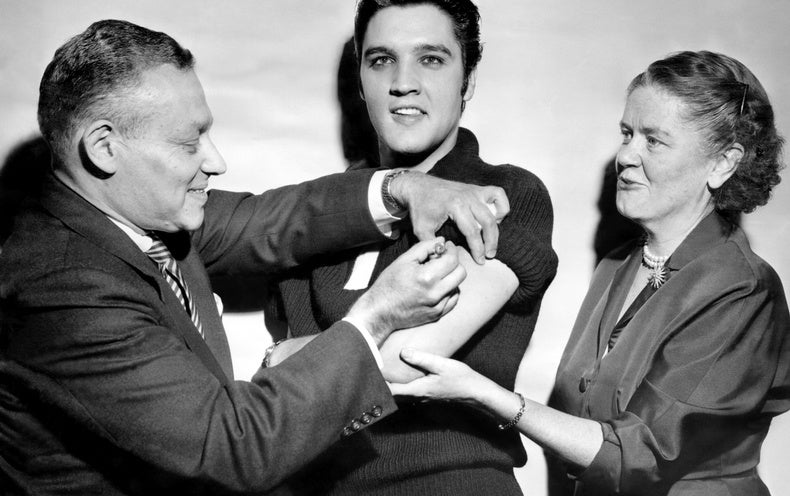

Nearly as notable, from the perspective of 2021, was the public service Elvis performed backstage, allowing himself to be photographed receiving the polio vaccine, in hopes his legions of admirers would follow suit.

Elvis’ third visit to Sullivan’s show, January 6th, 1957, would prove to be his last, owing to the astronomical fee his manager Colonel Tom Parker set for future television appearances: $300,000 with the promise of two guest spots and an hour-long special. An attempt to book Elvis for Sullivan’s 10th anniversary celebration, was thwarted by the fact that Elvis was abroad, serving in the Army.

Another massive audience tuned in for another helping of hits — “Hound Dog,” “Love Me Tender,” “Heartbreak Hotel,” and “Don’t Be Cruel,” as well as newer material — “Too Much” and “When My Blue Moon Turns To Gold Again.”

Between songs, Sullivan advised the swooning teenagers to rest their larynxes and introduced Elvis’ performance of the gospel standard, “Peace in the Valley,” by urging viewers to contribute to a Hungarian refugee relief fund Elvis supported.

While many fans persist in the belief that the gospel number was included as an affectionate nod to the singer’s beloved mother, Gladys, a letter from Colonel Parker’s assistant to Elvis suggests that the choice had more to do with his host:

Mr. Sullivan thought it might be very appropriate for you to sing a hymn or a semi-religious song on the show. You certainly can sing a hymn very effectively and I think it would make a very strong impression on all the viewers. It has been suggested that a song like ‘Peace in the Valley’ might be held in readiness. We have obtained the music on this song and are forwarding it to you.”

This time, home viewers really were left to guess what was going on below the star’s sequined vest and open collared blouse, described by Marcus as “the outlandish costume of a pasha, if not a harem girl:”

From the make-up over his eyes, the hair falling in his face, the overwhelmingly sexual cast of his mouth, he was playing Rudolph Valentino in The Sheik, with all stops out. That he did so in front of the Jordanaires, who this night appeared as the four squarest-looking men on the planet, made the performance even more potent.

Sullivan’s first co-producer, Marlo Lewis, intimated that the decision to formalize a waist-up policy for Elvis’ third visit was sparked by a rumor that had dogged his prior appearances. To wit:

Elvis has been hanging a small soft-drink bottle from his groin underneath his pants, and when he wiggles his leg it looks as though his pecker reaches down to his knee!

Meanwhile, it appeared Sullivan was no longer willing to be lumped in with Elvis’ detractors, closing the show by saying:

I wanted to say to Elvis Presley and the country that this is a real decent, fine boy, and wherever you go, Elvis, we want to say we’ve never had a pleasanter experience on our show with a big name than we’ve had with you. So now let’s have a tremendous hand for a very nice person!

Had Elvis won him over, or was it, as cultural critic Tim Parrish asserts, that Colonel Parker, “had threatened to remove Elvis from the show if Sullivan did not apologize for telling the press that Elvis’s ‘gyrations’ were immoral.”

Watch all of Elvis Presley’s performances on The Ed Sullivan Show in HD here.

For a glimpse of the 1956 Gibson J‑200 Elvis played in that final appearance, and speculation as to whether he crossed paths with fellow guests Carol Burnett and Lena Horne, watch Graceland archivist Angie Marchese’s show and tell of ephemera related to his stints on the Ed Sullivan Show.

Related Content:

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.