Coming after the maturation of the market for high-fidelity stereo systems but before the advent of home video, the nineteen-seventies provided just the right cultural and economic conditions for a heroic age of the record album. What’s Going On, Blue, Blood on the Tracks, Exile on Main Street, Born to Run, Rumours, Aja: that these and other seventies releases always rank high on best-of-all-time lists can be no accident. But no other mega-selling album of that decade achieved quite the combination of commercial and critical success as Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon, which was originally released fifty years ago yesterday — and which remains on the Billboard charts today.

“In 1973, Pink Floyd was a somewhat known progressive rock band,” writes neuroscientist and music producer Daniel Levitin, but The Dark Side of the Moon “catapulted them into world class rock-star status.”

Its masterful engineering “propelled the music off of any sound system to become an all-encompassing, immersive experience” comprising songs that “flow into one another symphonically, with seamless musical coherence, as though written as part of a single melodic and harmonic gesture. Lyric themes of madness and alienation connect throughout,” enlivened by an “array of new electronic sounds, spatialization, pitch and time bending” as well as “clocks, alarms, chimes, cash registers, footsteps” and other elements not normally heard in rock music.

This description comes from an essay Levitin wrote for the Library of Congress in 2012, when The Dark Side of the Moon was inducted into the US National Recording Registry. For the album’s fiftieth anniversary, National Public Radio’s Morning Edition invited him to psychoanalyze it on-air. “Themes of madness and alienation permeate the record,” he says, making reference to the story of departed Pink Floyd member Syd Barrett. But “we can’t know for sure which specific lyrics were about Barrett, as opposed, more generally, to mental anguish,” a condition bound to afflict anyone too deep into the rock-star lifestyle.

In The Dark Side of the Moon’s lyrics Levitin hears Pink Floyd co-founder Roger Waters’ metaphorical treatment of the difficult decision to fire Barrett, as well as his realization that “life wasn’t going to start later. It had started. And the idea of ‘Time’ was to grasp the reins and start guiding your own destiny.” As on the album as a whole, the theme comes through in not just the words but the soundscape: “Right off the bat, they’re playing with time. You hear that clop-clop sound, like a heartbeat or a clock ticking. And you think that the higher-pitched one is the downbeat. But as soon as the instruments come in, you realize you’re off the beat, and everything’s upside down. And your sense of time is distorted.”

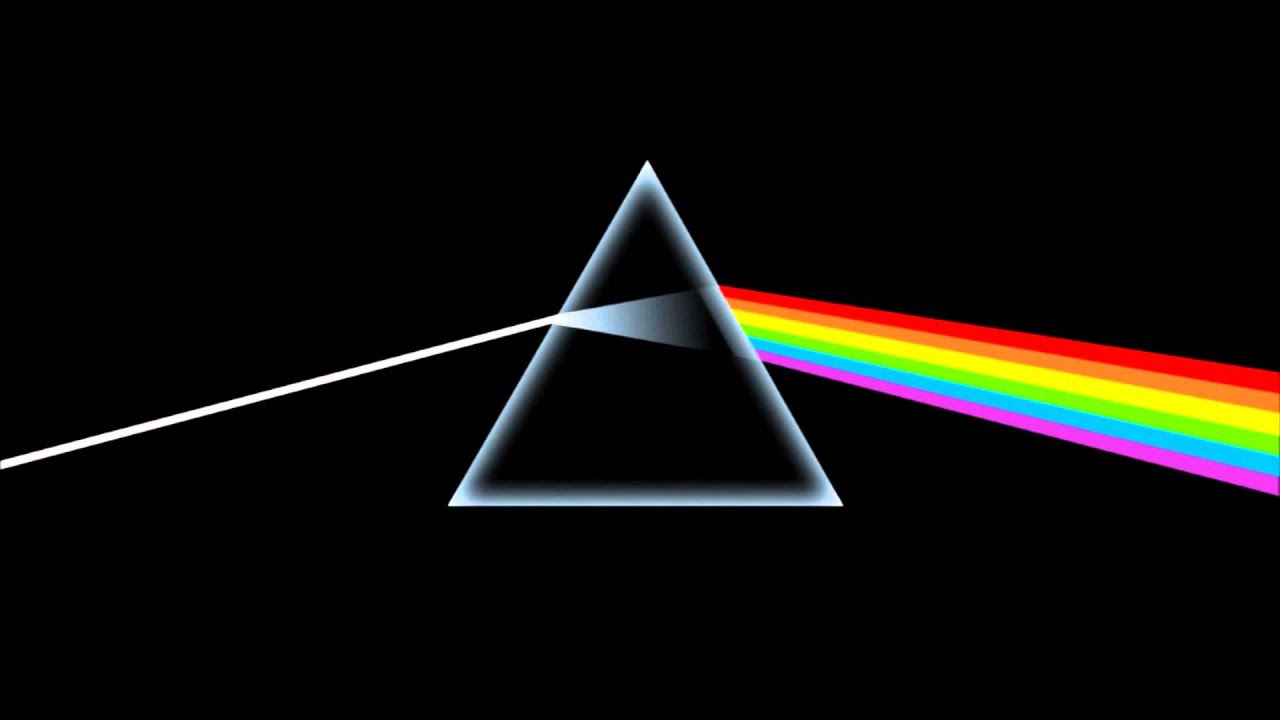

Musical artistry accounts in part for the album’s massive success in part, but only in part. Storm Thorgerson’s iconic cover art, still seen on the walls of college dorm rooms today, also had something to do with its success as both cultural phenomenon and consumer product. But it could hardly have sold more than 45 million copies to date without chancing to hit the zeitgeist at a favorable angle: as Pink Floyd drummer Nick Mason said, it was “not only about being a good album but also about being in the right place at the right time.” And with the heroic age of the album long over, The Dark Side of the Moon — a newly re-recorded version of which Waters announced just this year — isn’t about to be eclipsed.

Related content:

Pink Floyd’s Entire Studio Discography is Now on YouTube: Stream the Studio & Live Albums

The Dark Side of the Moon Project: Watch an 8‑Part Video Essay on Pink Floyd’s Classic Album

Watch Documentaries on the Making of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon and Wish You Were Here

Download Pink Floyd’s 1975 Comic Book Program for The Dark Side of the Moon Tour

A Live Studio Cover of Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon, Played from Start to Finish

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.