We didn’t realize it at the time, but Michel Gondry was one of the last great music video directors, creating mini-epics just before the music industry collapsed, budgets disappeared, and now your cousin with a Canon 7D is following his friend’s band around in a field and putting *that* up on Vimeo. Maybe Gondry too saw the writing on the wall, because, by the beginning of the ‘aughts, he was inching his way into Hollywood, first with Human Nature and then striking paydirt with the Charlie Kaufman-scripted Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, one of the best French films ever made that wasn’t French (apart from the director).

But in the twilight of music videos, Gondry’s best work combined new technology with the homemade, DIY aesthetic. His interest in fractals, mathematics, and logical paradoxes and loops went into the mix. As did his interest in the machinery and artifice of movie making. And as did his romantic, autobiographical side. What follows is a small selection of some of his best, most complex music videos.

Gondry directed several videos for Björk, starting with “Human Behavior,” her first solo single, but 1997’s “Bachelorette” (top) goes beyond playful into heartbreaking. A riff on an infinitely recursive poem, a story that is about the telling of itself, the video finds Björk discovering a book in the woods that begins to write itself. As she finds a publisher, gains success, and sees the book turned into a musical, the story is told again, and then again, a play within a play within a play. But each version is analog, not digital, and loses something in the process, and the forest creeps back in to claim its work.

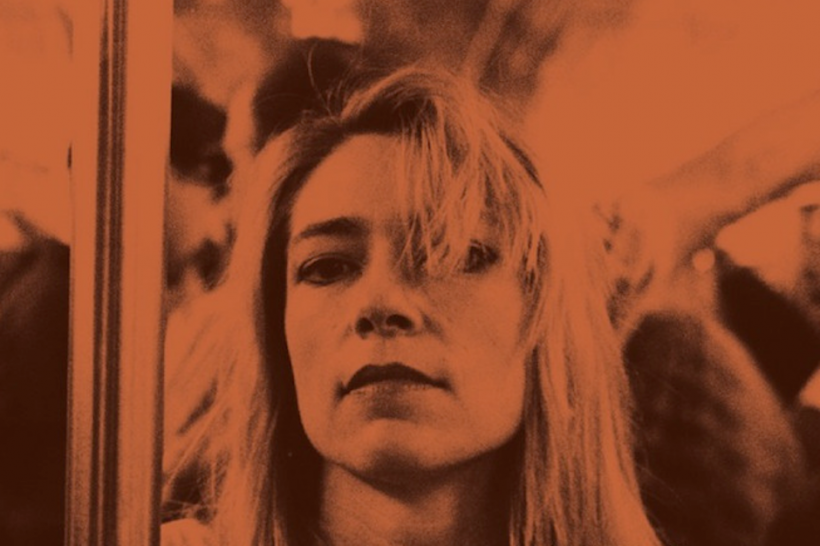

Similarly, in this video for The Chemical Brothers’ song “Let Forever Be” (1999) Gondry sets up two worlds, one on digital video, where our heroine attempts to wake up and go to work at a department store; and another shot on film, where the girl’s numerous doppelgängers parody her struggle and her grip on sanity through choreographed dance numbers. This illustrates a familiar Gondry equation: If A and B, then A+B equals freakout madness time. The colorbars of video production loom nearby to further the idea of irreality, and a cheesy VideoToaster-style effect rescues us at the end.

As far as we know, Radiohead’s “Knives Out” (2001) has nothing to do with hospitals, but Gondry took this cannibalistic song and made one of his most personal videos. Here Thom Yorke stands in for the director, as Gondry offers a mea culpa about a relationship that went past its expiration date, when his girlfriend developed an illness and he couldn’t bear to break up with her. All of that is laid out, in sad, fever-dream detail, in this single-take video that features a lot of his obsessions: toys, television, loops, and a shuffling of symbols and motifs. Look for Gondry’s son briefly playing on the floor.

And finally:

Not to go out with a sour note, here’s Gondry’s adventurous 1994 video for the swallowed-by-history Lucas. “Lucas with the Lid Off” is one of Gondry’s first one-take masterpieces that shows how the magic is made while still being magical. (The current kings of single-take music videos, OK Go, owe their success to Gondry.) It’s also a video that tries to give each sampled loop its own element within the video, looking forward to his work for Daft Punk (“Around the World”) and The Chemical Brothers (“Star Guitar”).

Gondry continues to make videos–he made one last year for Metronomy’s “Love Letters,” but his attention is really elsewhere. Enjoy these gems from his classic era.

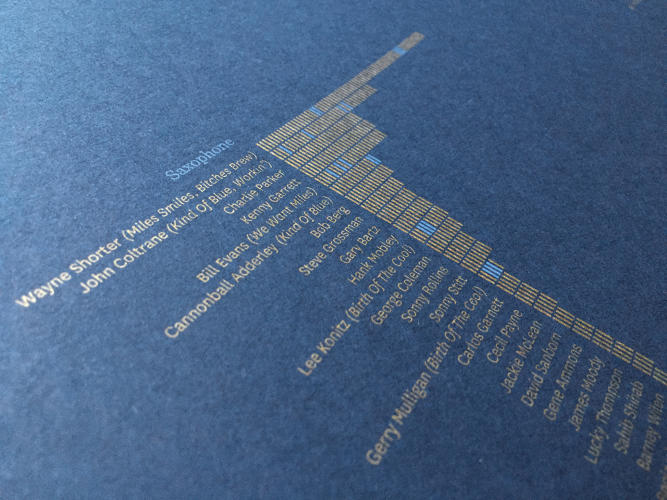

Note: Gondry’s 1988 short animated film, Jazzmosphere, an exploration of jazz and images, has been added to our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the FunkZone Podcast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills and/or watch his films here.