Hang around this site long enough and you’ll learn a thing or two about electronic music, whether it’s a very brief history of the Moog synthesizer, or the Theremin, or an enormous, obscure ancient ancestor, the Telharmonium. These mini-lessons are dwarfed, however, by the amount of information you’ll find on the site 120 Years of Electronic Music, wherein you can read about such strange creatures as the Choralcelo, the Staccatone, the Pianorad, Celluphone, Electronde, and Vibroexponator. Such oddities abound in the very long history of electronic musical instruments, which the site defines as “instruments that generate sounds from a purely electronic source rather than electro-mechanically or electro-acoustically.”

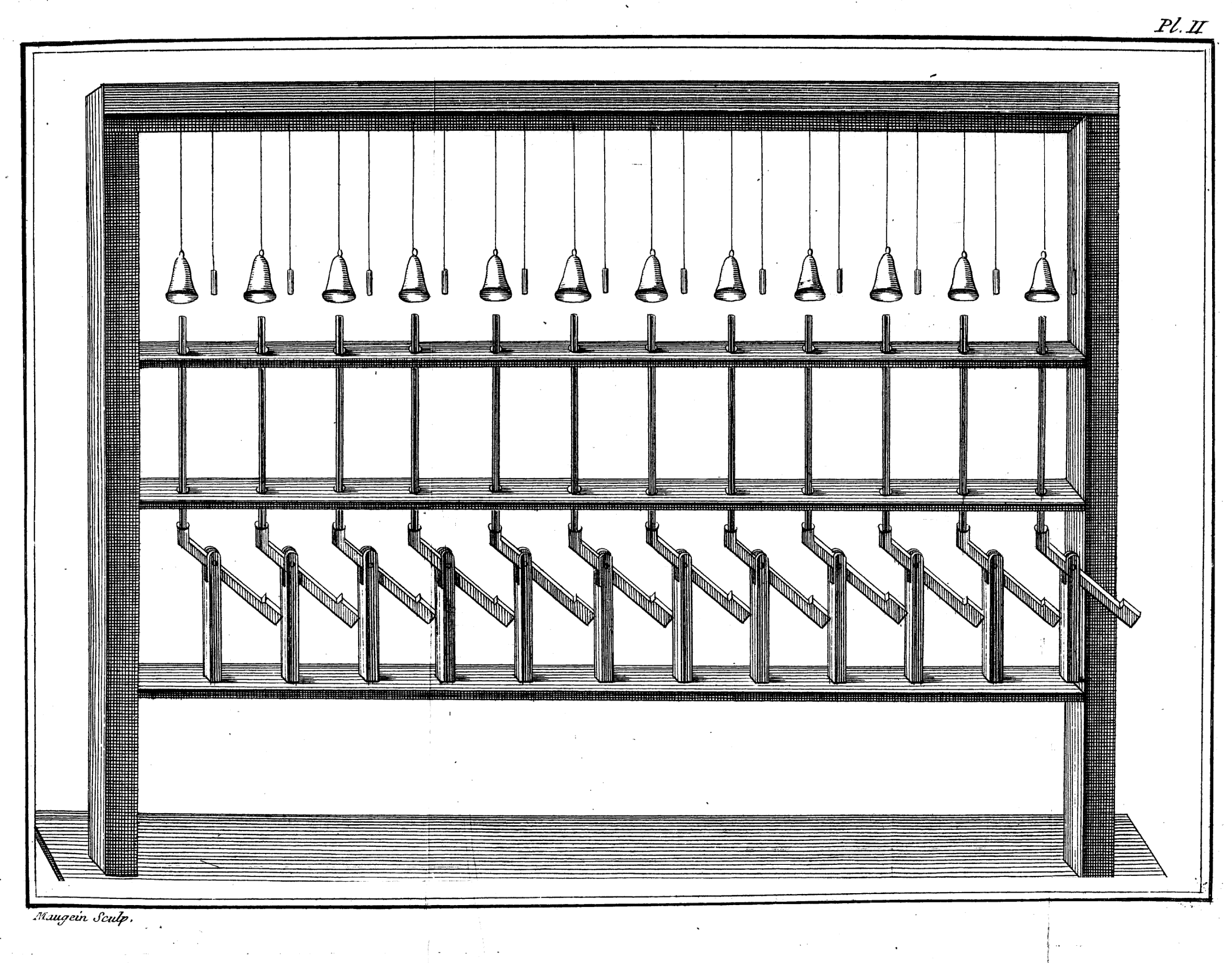

Despite these rather strict technical parameters, the site’s author Simon Crab admits that the boundaries “do become blurred with, say, Tone Wheel Generators and tape manipulation of the Musique Concrete era.” Then there are precursor instruments that predate the discovery and harnessing of electricity, such as the Clavecin Magnetique, above, invented by Abbé Bertholon de Saint-Lazare in 1789, a “simple instrument which produced sounds by attracting metal clappers to strike tuned bells by raising and lowering magnets operated by a keyboard.”

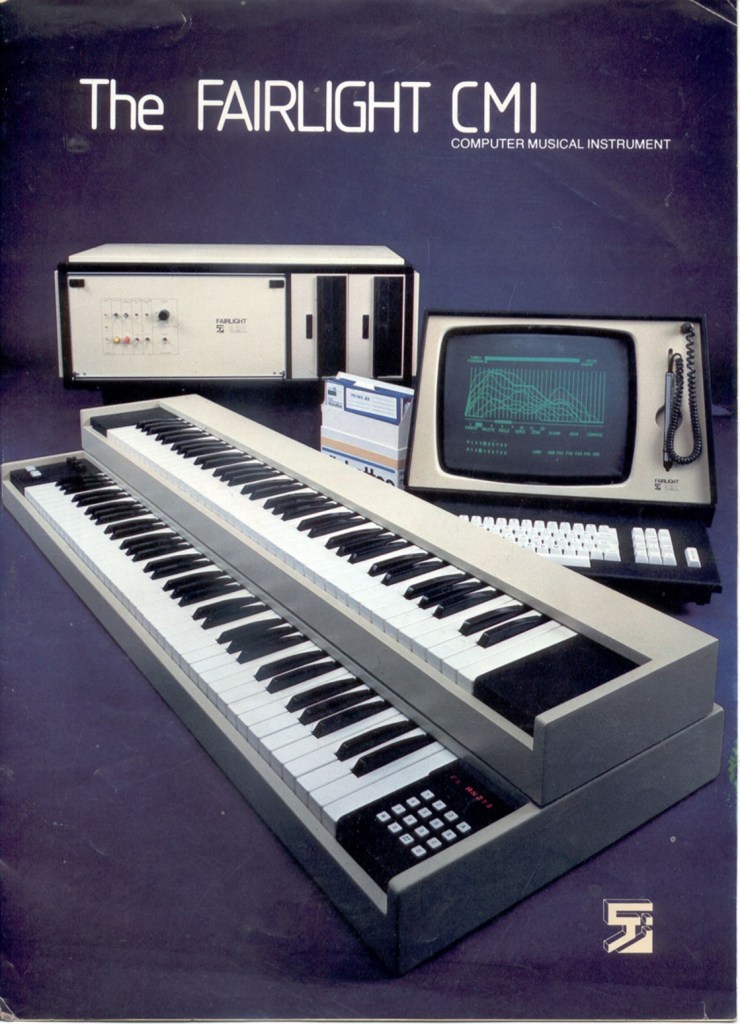

Yet the primary focus of 120 Years of Electronic Music is a period of growth and development from the late 1800s to the 1970s, when early digital synthesizers like the Fairlight (top) appeared. Thus, we should not expect here “an exhaustive list of recent commercial synthesizers or software packages”—the stuff of modern dance, pop, hip-hop, etc. Crab’s intent is academic, “encyclopedic, pedagogical,” and pitched to musicologists as well as “Synthesizer Geeks” likely to appreciate the niceties of the 1961 DIMI & Helsinki Electronic Music Studio.

But even non-academics and non-geeks can learn much from the history of such unusual instruments as the Klaviatursphäraphon (above), one of several creations of German composer Jörg Mager in his pursuit of “a new type of utopian ‘free’ music by means of new electronic cathode-ray musical instruments.”

Amidst the weird obscurities and high-concept musical theory, you’ll also find old favorites that revolutionized pop music, like the Hammond Organ (see a making-of promotional video above), the various iterations of Moog synthesizers, and of course the Fairlight CMI (short for Computer Musical Instrument). Invented by Kim Ryrie and Peter Vogel in Australia in 1979, the Fairlight is affectionately known as the “mother of all samplers,” and its technology jumpstarted the revolution in computer music from the 80s to today. You can see Vogel demonstrate the first version of his Fairlight in this video, or—for a slightly less geeky intro—see Peter Gabriel demonstrate it below (or watch Herbie Hancock and Quincy Jones show you how it’s done in a clip from Sesame Street.)

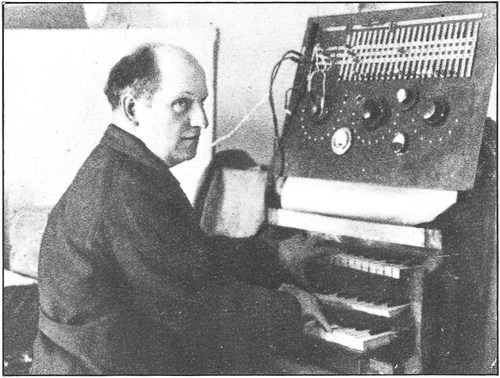

The Hammond, Moogs, and Fairlight aside, very few of the instruments featured on 120 Years of Electronic Music had any kind of direct impact on popular music. But many of them, like Hugh Le Caine’s 1945 Electronic Sackbut, influenced the influencers, and they all represent some evolutionary step forward, or sideways, in the development of the sounds we hear all around us now in every possible genre.

Additionally, Crab’s historical project explores what he calls “the dichotomy between radical culture and radical social change,” with discussions on the links between Bolshevism and the avant-garde and modernism and fascism—discussions of keen interest to cultural historians and critical theorists. Oh, and the name? “The project,” Crab explains, “was begun in 1996; considering electronic music started around 1880 this was quite an accurate title for the time.” It’s now “a bit out of date but… something of a brand-name.” We’ll forgive him this minor chronological inaccuracy for the tremendous service his open access encyclopedia offers to scholars and enthusiasts alike. Explore it here.

Related Content:

Hear the Greatest Hits of Isao Tomita (RIP), the Father of Japanese Electronic Music

The History of Electronic Music in 476 Tracks (1937–2001)

Hear Seven Hours of Women Making Electronic Music (1938- 2014)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness