Scientists need hobbies. The grueling work of navigating complex theory and the politics of academia can get to a person, even one as laid back as Dartmouth professor and astrophysicist Stephon Alexander. So Alexander plays the saxophone, though at this point it may not be accurate to call his avocation a spare time pursuit, since John Coltrane has become as important to him as Einstein, Kepler, and Newton.

Coltrane, he says in a 7‑minute TED talk above, “changed my whole research direction… led to basically a discovery in physics.” Alexander then proceeds to play the familiar opening bars of “Giant Steps.” He’s no Coltrane, but he is a very creative thinker whose love of jazz has given him a unique perspective on theoretical physics, one he shares, it turns out, with both Einstein and Coltrane, both of whom saw music and physics as intuitive, improvisatory pursuits.

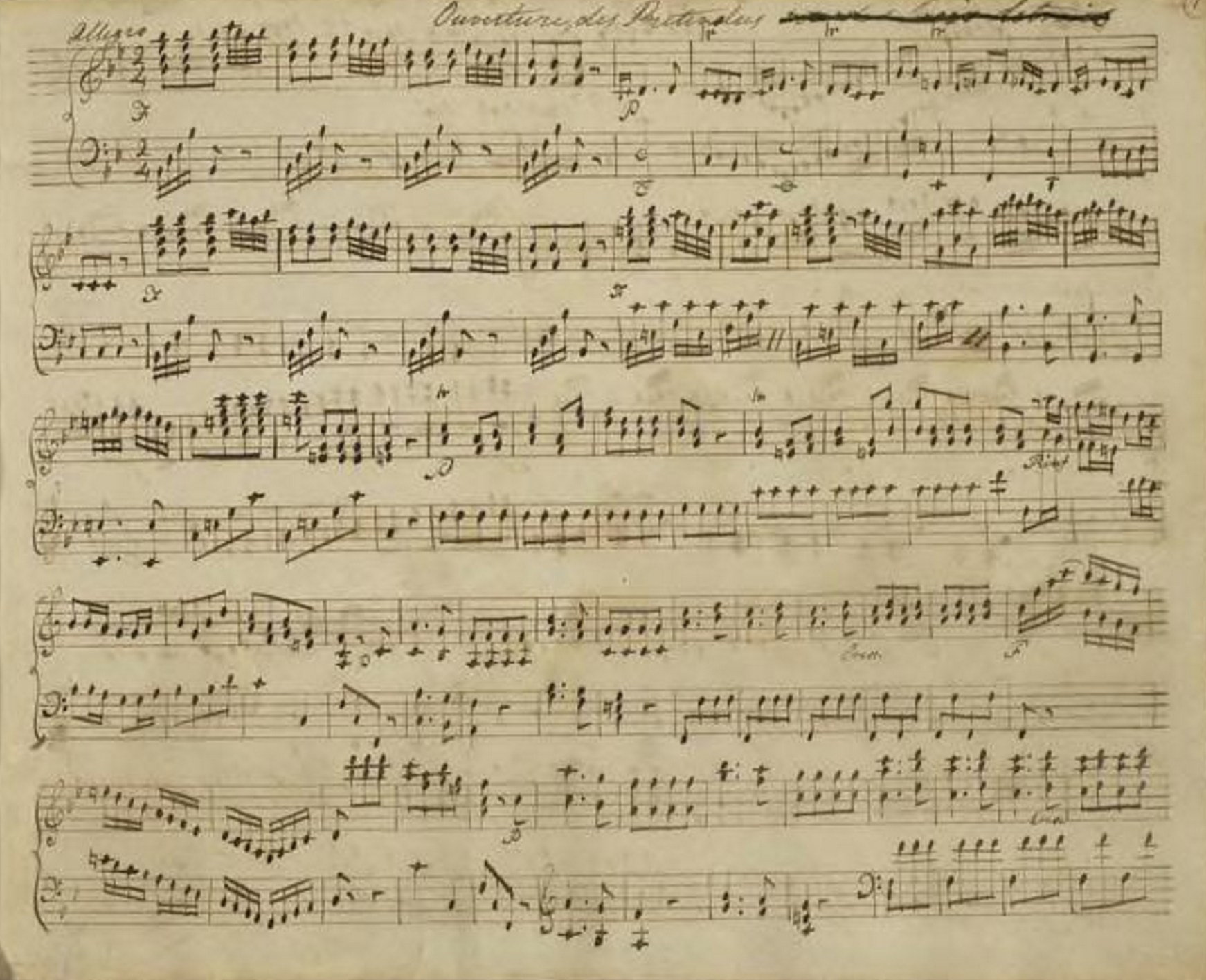

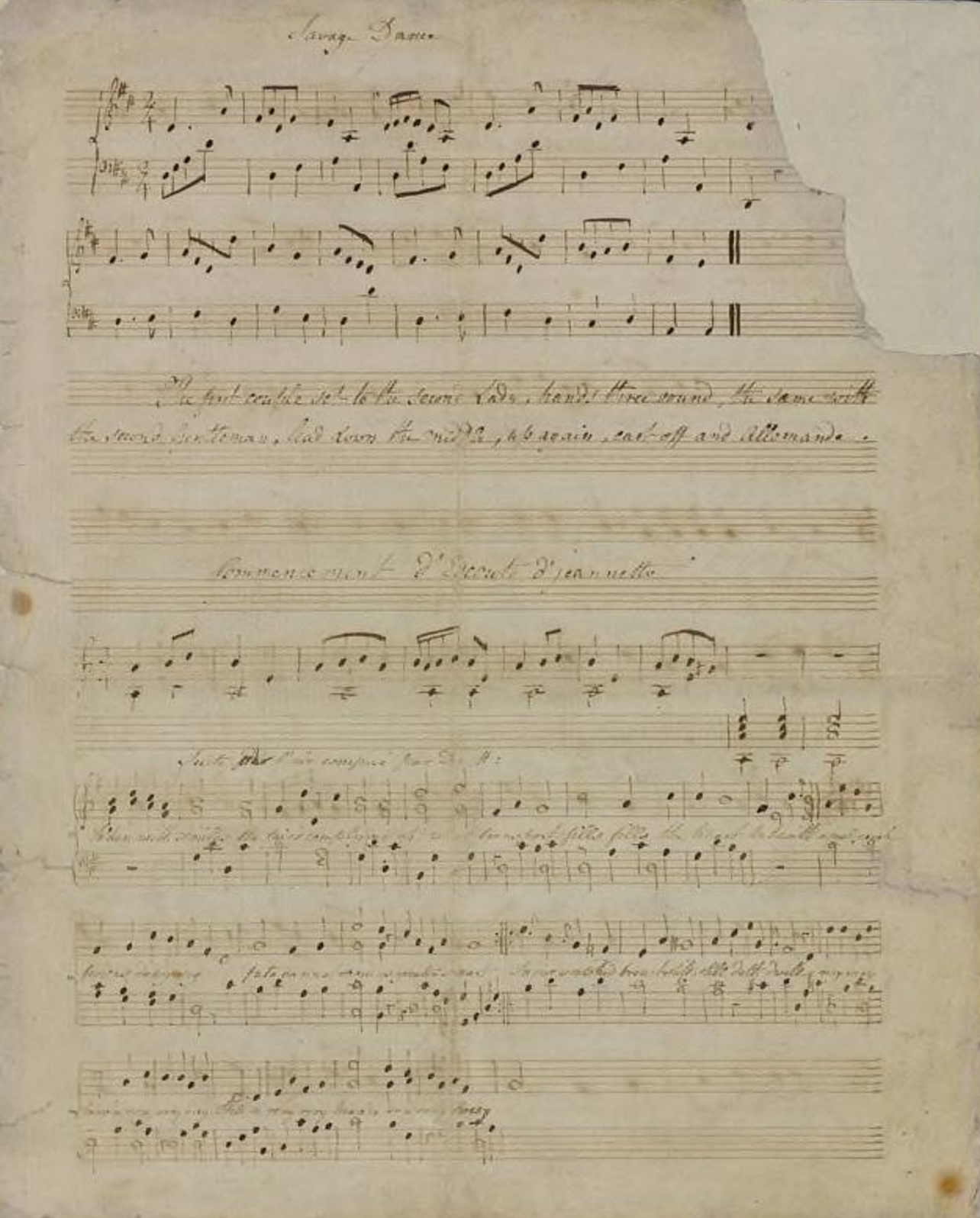

Alexander describes his jazz epiphany as occasioned by a complex diagram Coltrane gave legendary jazz musician and University of Massachusetts professor Yusef Lateef in 1967. “I thought the diagram was related to another and seemingly unrelated field of study—quantum gravity,” he writes in a Business Insider essay on his discovery, “What I had realized… was that the same geometric principle that motivated Einstein’s theory was reflected in Coltrane’s diagram.”

The theory might “immediately sound like untestable pop-philosophy,” writes the Creators Project, who showcase Alexander’s physics-inspired musical collaboration with experimental producer Rioux (sample below). But his ideas are much more substantive, “a compelling cross-disciplinary investigation,” recently published in a book titled The Jazz of Physics: The Secret Link Between Music and the Structure of the Universe.

Alexander describes the links between jazz and physics in his TED talk, as well as in the brief Wired video further up. “One connection,” he says, is “the mysterious way that quantum particles move.… According to the rules of quantum mechanics,” they “will actually traverse all possible paths.” This, Alexander says, parallels the way jazz musicians improvise, playing with all possible notes in a scale. His own improvisational playing, he says, is greatly enhanced by thinking about physics. And in this, he’s only following in the giant steps of both of his idols.

It turns out that Coltrane himself used Einstein’s theoretical physics to inform his understanding of jazz composition. As Ben Ratliff reports in Coltrane: The Story of a Sound, the brilliant saxophonist once delivered to French horn player David Amram an “incredible discourse about the symmetry of the solar system, talking about black holes in space, and constellations, and the whole structure of the solar system, and how Einstein was able to reduce all of that complexity into something very simple.” Says Amram:

Then he explained to me that he was trying to do something like that in music, something that came from natural sources, the traditions of the blues and jazz. But there was a whole different way of looking at what was natural in music.

This may all sound rather vague and mysterious, but Alexander assures us Coltrane’s method is very much like Einstein’s in a way: “Einstein is famous for what is perhaps his greatest gift: the ability to transcend mathematical limitations with physical intuition. He would improvise using what he called gedankenexperiments (German for thought experiments), which provided him with a mental picture of the outcome of experiments no one could perform.”

Einstein was also a musician—as we’ve noted before—who played the violin and piano and whose admiration for Mozart inspired his theoretical work. “Einstein used mathematical rigor,” writes Alexander, as much as he used “creativity and intuition. He was an improviser at heart, just like his hero, Mozart.” Alexander has followed suit, seeing in the 1967 “Coltrane Mandala” the idea that “improvisation is a characteristic of both music and physics.” Coltrane “was a musical innovator, with physics at his fingertips,” and “Einstein was an innovator in physics, with music at his fingertips.”

Alexander gets into a few more specifics in his longer TEDx talk above, beginning with some personal background on how he first came to understand physics as an intuitive discipline closely linked with music. For the real meat of his argument, you’ll likely want to read his book, highly praised by Nobel-winning physicist Leon Cooper, futuristic composer Brian Eno, and many more brilliant minds in both music and science.

Related Content:

Free Online Physics Courses

The Musical Mind of Albert Einstein: Great Physicist, Amateur Violinist and Devotee of Mozart

CERN’s Cosmic Piano and Jazz Pianist Jam Together at The Montreux Jazz Festival

Bohemian Gravity: String Theory Explored With an A Cappella Version of Bohemian Rhapsody

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness