In 1958, Link Wray released his bluesy instrumental “Rumble,” known for its pioneering use of reverb and distortion. The gritty, seductive tune became a huge hit with the kids, but grown-ups found the sound threatening, reminiscent of scary gang scenes in West Side Story and growing fears over “Juvenile Delinquency”—a national anxiety marked by the 1955 release of Blackboard Jungle and its introduction of Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock.”

Just three years later, “Rumble” made middle class citizens so nervous that the song has the distinction of being the only instrumental ever banned from radio play in the U.S. And yet, that honor is somewhat misleading. It’s true many radio stations refused to play the song, or any rock and roll records at all, but it did receive enough exposure—from people like American Bandstand’s Dick Clark, no less—to remain in the top 40 for ten weeks in 1958.

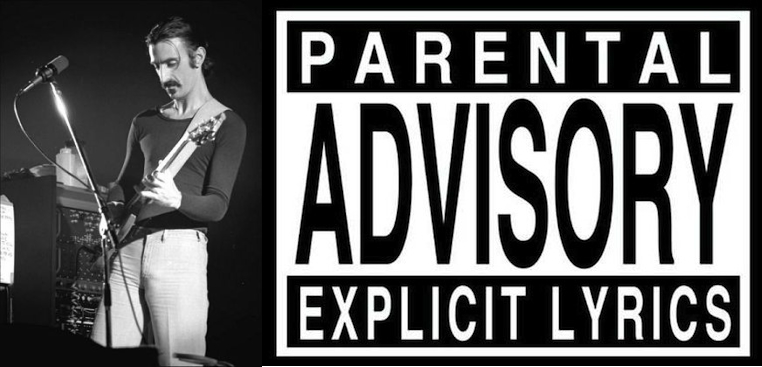

Fast-forward thirty years from Blackboard Jungle panic, and we find the country in the midst of another national freakout about the kids and their music, this one spearheaded by the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC), formed by Tipper Gore and three other so-called “Washington Wives” who sought to place warning labels on “explicit” popular albums and otherwise impose moralistic guidelines on music and movies. Congressional hearings in 1985 saw the odd trio of Twisted Sister’s Dee Snider, mild-mannered folk star John Denver, and virtuoso prog-weirdo Frank Zappa testifying before the Senate against censorship. The fiercely libertarian Zappa’s opposition to the PMRC became something of a crusade, and the following year he appeared on Crossfire to argue his case.

PMRC backlash from musicians everywhere began to clutter the pop cultural landscape. Glenn Danzig released his anti-PMRC anthem, “Mother”; Ice‑T’s The Iceberg/Freedom of Speech viciously attacked Gore and her organization; NOFX released their E.P. The P.M.R.C. Can Suck on This… just a small sampling of dozens of anti-PMRC songs/albums/messages after those infamous hearings. But we can credit Zappa with founding the musical subgenera in his 1985 Frank Zappa Meets the Mothers of Prevention, which included “Porn Wars,” above, a mashup of distorted samples from the hearings.

All of these records received the requisite “Good Housekeeping Seal of Disapproval,” the now-familiar stark black-and-white parental warning label (top). Zappa’s album cover pre-empted the inevitable stickering with a bright yellow and red box reading “Warning Guarantee,” full of tongue-in-cheek small print like “GUARANTEED NOT TO CAUSE ETERNAL TORMENT IN THE PLACE WHERE THE GUY WITH THE HORNS AND POINTED STICK CONDUCTS HIS BUSINESS.” All this incessant needling of the PMRC must have really got to them, fans figured, when Zappa’s 1986 record Jazz from Hell began appearing, it’s said, in record stores with a parental advisory label—on an album without lyrics of any kind.

But did Zappa’s Grammy-award-winning instrumental record (above) really get the explicit content label? And was such labeling retaliation from the PMRC, as some believed? These claims have circulated for years on message boards, in books like Peter Blecha’s Taboo Tunes: A History of Banned Bands & Censored Songs, and on Wikipedia. And the answer is both yes, and no. Jazz from Hell did not get the familiar “Parental Advisory: Explicit Lyrics” label, nor was it specifically targeted by Gore’s organization.

The album was, however, stickered in 1990—notes Dave Thompson’s The Music Lover’s Guide to Record Collecting—by “the Pacific Northwest chain of Fred Meyer department stores,” who gave it “the retailer’s own ‘Explicit Lyrics’ warning, despite the fact that the album was wholly instrumental.” This is likely due to the word “hell” and the title of the song “G‑Spot Tornado.” So it may be fair to say that Zappa’s Jazz from Hell is the only fully instrumental album to receive an “Explicit Lyrics” warning, inspired by, if not directly ordered by, the PMRC. Like the radio censorship of Link Wray’s “Rumble,” this regional seal of disapproval did not in the least prevent the record from receiving due recognition. But it makes for a curious historical example of the absurd lengths people have gone to in their fear of modern pop music.

Related Content:

Frank Zappa Debates Censorship on CNN’s Crossfire (1986)

Hear the Musical Evolution of Frank Zappa in 401 Songs

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness