Materials like carbon fiber and Lucite have been making their way into classical stringed instrument design for many years, and we’ve recently seen the 3‑D printed electric violin come into being. It’s an impressive-sounding instrument, one must admit. But trained classical violinists, luthiers, music historians, and collectors all agree: the violin has never really been improved upon since around the turn of the 18th century, when two its finest makers—the Amati and Stradivari families—were at their peak. A few studies have tried to poke holes in the argument that such violins are superior in sound to modern makes. There are many reasons to view these claims with skepticism.

By the time the most expert Italian luthiers began making violins, the instrument had already more or less assumed its final shape, after the long evolution of its f‑holes into the perfect sonic conduit. However, Amati and Stradivari not only refined the violin’s curves, edges, and neck design, they also introduced new chemical processes meant to protect the wood from worms and insects.

One biochemistry professor discovered that these chemicals “had the unintended result of producing the unique sounds that have been almost impossible to duplicate in the past 400 years.”

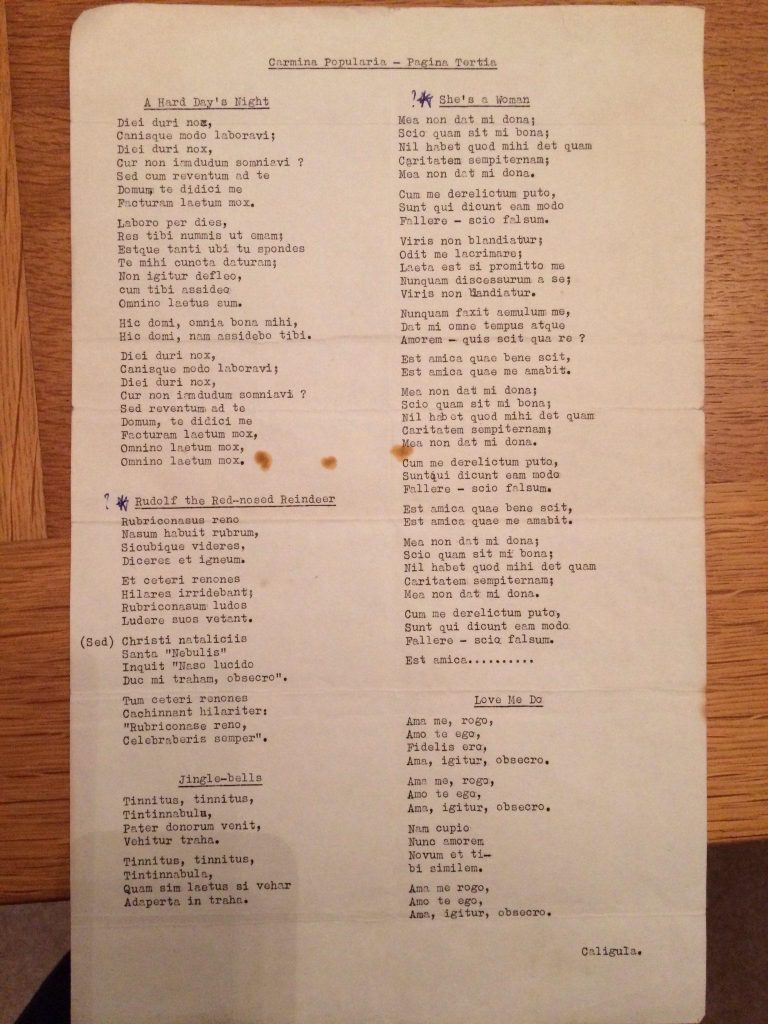

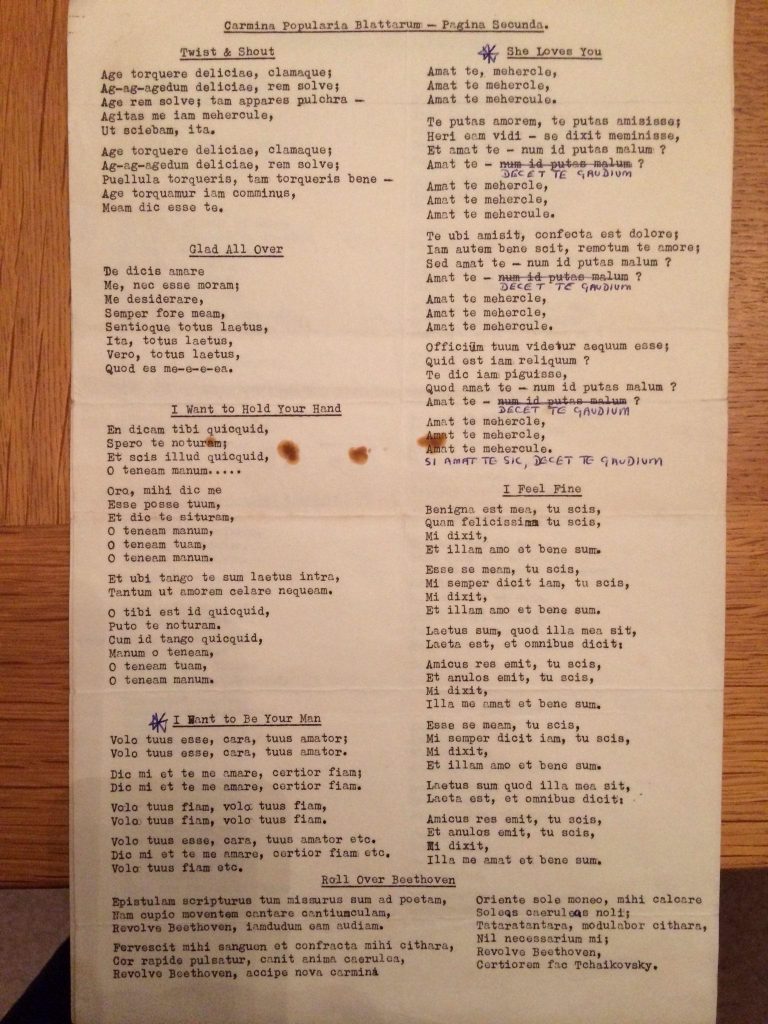

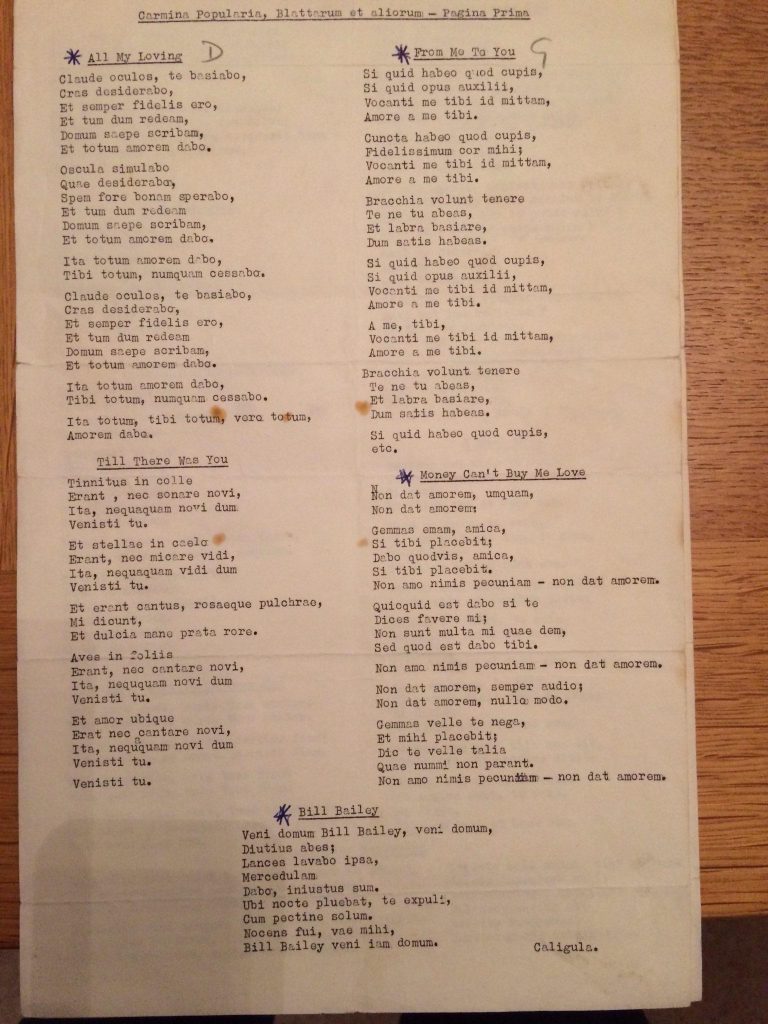

Knowing they had hit upon a winning formula, the top makers passed their techniques down for several generations, making hundreds of violins and other instruments. A great many of these instruments survive, though a market for fakes thrives alongside them. The instruments you see in the videos here are the real thing, four of the world’s oldest and most priceless violins, all of them residing at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. These date from the late 1600s to early 1700s, and were all made in Cremona, the Northern Italian home of the great masters. At the top of the post, you can see Sean Avram Carpenter play Bach’s Sonata No. 1 in G minor on a 1669 violin made by Nicolò Amati.

The next three videos are of violins made by Antonio Stradivari, perhaps once an apprentice of Amati. Each instrument has its own nickname: “The Gould” dates from 1693 and is, writes the Met, “the only [Stradivari] in existence that has been restored to its original Baroque form.” We can see Carpenter play Bach’s Sonata in C major on this instrument further up. Both “The Gould” and the Amati violin were made before modifications to the angle of the neck created “a louder, more brilliant tone.” Above you can hear “The Francesca,” from 1694. Carpenter plays from “Liebesleid” by Fritz Kreisler with the pianist Gabriela Martinez. See if you can tell the difference in tone between this instrument and the first two, less modern designs.

The last violin featured here, “The Antonius,” made by Stradivari in 1717, gets a demonstration in front of a live audience by Eric Grossman, who plays the chaconne from Bach’s Partita No. 2 in D minor. This instrument comes from what is called Stradivari’s “Golden Period,” the years between 1700 and 1720. Some of the most highly valued of Stradivarii in private hands date from around this time. And some of these instruments have histories that may justify their staggering price tags. The Molitor Stradivarius, for example, was supposedly owned by Napoleon. But no matter the previous owner or number of millions paid, every violin created by one of these makers carries with it tremendous prestige. Is it deserved? Hearing them might make you a believer. Joseph Nagyvary, the Texas A&M professor emeritus who is discovering their secrets, tells us, “the great violin masters were making violins with more humanlike voices than any others of the time.” Or any since, most experts would agree.

Related Content:

What Does a $45 Million Viola Sound Like? Violist David Aaron Carpenter Gives You a Preview

The Art and Science of Violin Making

Why Violins Have F‑Holes: The Science & History of a Remarkable Renaissance Design

Behold the “3Dvarius,” the World’s First 3‑D Printed Violin

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness