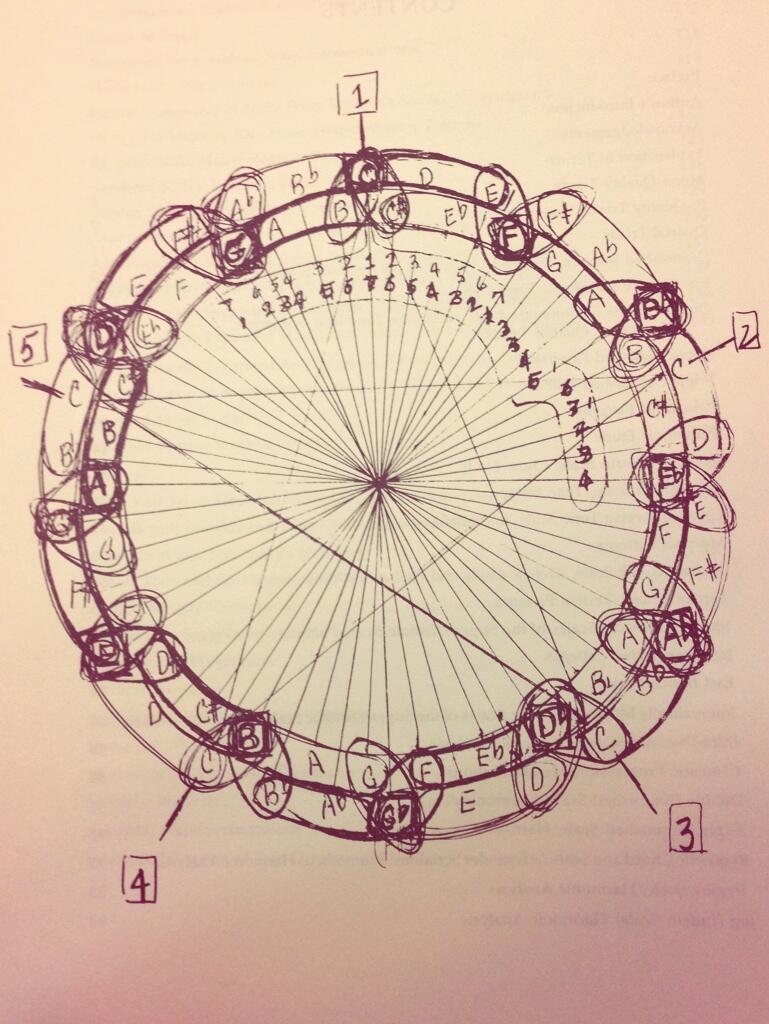

Physicist and saxophonist Stephon Alexander has argued in his many public lectures and his book The Jazz of Physics that Albert Einstein and John Coltrane had quite a lot in common. Alexander in particular draws our attention to the so-called “Coltrane circle,” which resembles what any musician will recognize as the “Circle of Fifths,” but incorporates Coltrane’s own innovations. Coltrane gave the drawing to saxophonist and professor Yusef Lateef in 1967, who included it in his seminal text, Repository of Scales and Melodic Patterns. Where Lateef, as he writes in his autobiography, sees Coltrane’s music as a “spiritual journey” that “embraced the concerns of a rich tradition of autophysiopsychic music,” Alexander sees “the same geometric principle that motivated Einstein’s” quantum theory.

Neither description seems out of place. Musician and blogger Roel Hollander notes, “Thelonious Monk once said ‘All musicans are subconsciously mathematicians.’ Musicians like John Coltrane though have been very much aware of the mathematics of music and consciously applied it to his works.”

Coltrane was also very much aware of Einstein’s work and liked to talk about it frequently. Musican David Amram remembers the Giant Steps genius telling him he “was trying to do something like that in music.”

Hollander carefully dissects Coltrane’s mathematics in two theory-heavy essays, one generally on Coltrane’s “Music & Geometry” and one specifically on his “Tone Circle.” Coltrane himself had little to say publically about the intensive theoretical work behind his most famous compositions, probably because he’d rather they speak for themselves. He preferred to express himself philosophically and mystically, drawing equally on his fascination with science and with spiritual traditions of all kinds. Coltrane’s poetic way of speaking has left his musical interpreters with a wide variety of ways to look at his Circle, as jazz musician Corey Mwamba discovered when he informally polled several other players on Facebook. Clarinetist Arun Ghosh, for example, saw in Coltrane’s “mathematical principles” a “musical system that connected with The Divine.” It’s a system, he opined, that “feels quite Islamic to me.”

Lateef agreed, and there may be few who understood Coltrane’s method better than he did. He studied closely with Coltrane for years, and has been remembered since his death in 2013 as a peer and even a mentor, especially in his ecumenical embrace of theory and music from around the world. Lateef even argued that Coltrane’s late-in-life masterpiece A Love Supreme might have been titled “Allah Supreme” were it not for fear of “political backlash.” Some may find the claim tendentious, but what we see in the wide range of responses to Coltrane’s musical theory, so well encapsulated in the drawing above, is that his recognition, as Lateef writes, of the “structures of music” was as much for him about scientific discovery as it was religious experience. Both for him were intuitive processes that “came into existence,” writes Lateef, “in the mind of the musican through abstraction from experience.”

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook and BlueSky.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

John Coltrane’s Handwritten Outline for His Masterpiece A Love Supreme

John Coltrane’s ‘Giant Steps’ Animated

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness