These days everyone’s hung up on identity. But I don’t mean to talk politics, though my point is maybe inescapably political: the identities our jobs and incomes give us—the status or lack thereof—become so central to who we are in the world that they eclipse other essential aspects, eclipse the things we do strictly because it gives us pleasure to do them.

Music, dance, art, poetry.… These fall under what Alan Lomax called an experience of “the very core” of existence, “the adaptive style” of culture, “which enables its members to cohere and survive.” Culture, for Lomax, was neither an economic activity nor a racial category, neither an exclusive ranking of hierarchies nor a redoubt for nationalist insecurities. Cultures, plural, were peculiarly regional expressions of shared humanity across one interrelated world.

Lomax did have some paternalistic attitudes toward what he called “weaker peoples,” noting that “the role of the folklorist is that of the advocate of the folk.” But his advocacy was not based in theories of supremacy but of history. We could mend the ruptures of the past by adding “cultural equity… to the humane condition of liberty, freedom of speech and religion, and social justice,” wrote the idealistic Lomax. “The stuff of folklore,” he wrote elsewhere, “the orally transmitted wisdom, art and music of the people, can provide ten thousand bridges across which men of all nations may stride to say, ‘You are my brother.’”

Lomax’s idealism may seem to us quaint at best, but I dare you to condemn its results, which include connecting Lead Belly and Woody Guthrie to their global audiences and preserving a good deal of the folk music heritage of the world through tireless field and studio recording, documentation and memoir, and institutions like the Association for Cultural Equity (ACE), founded by Lomax in 1986 to centralize and make available the vast amount of material he had collected over the decades.

In another archival project, Lomax’s Global Jukebox, we get to see rigorous scholarly methods applied to examples from his vast library of human expressions. The online project catalogues the work in musicology of Lomax and his father John, who both took on a “life long mission to document not only America’s cultural roots, but the world’s as well,” notes an online brochure for the Global Jukebox. Lomax believed that “music, dance and folklore of all traditions have equal value” and are equally worthy of study. The Global Jukebox carries that belief into the 21st century.

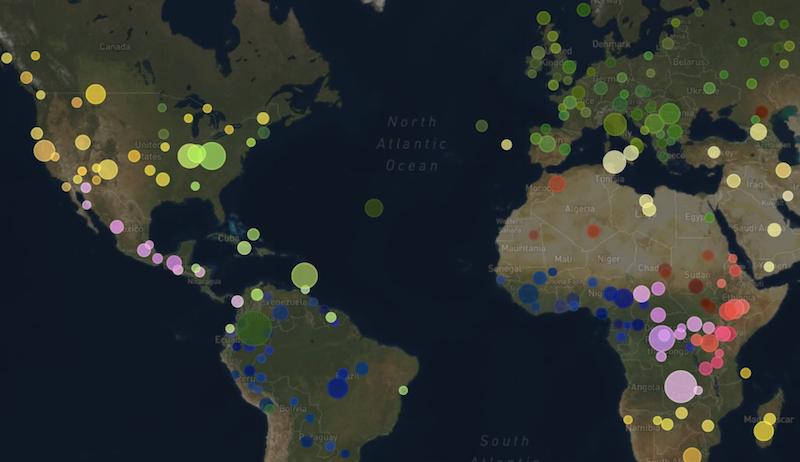

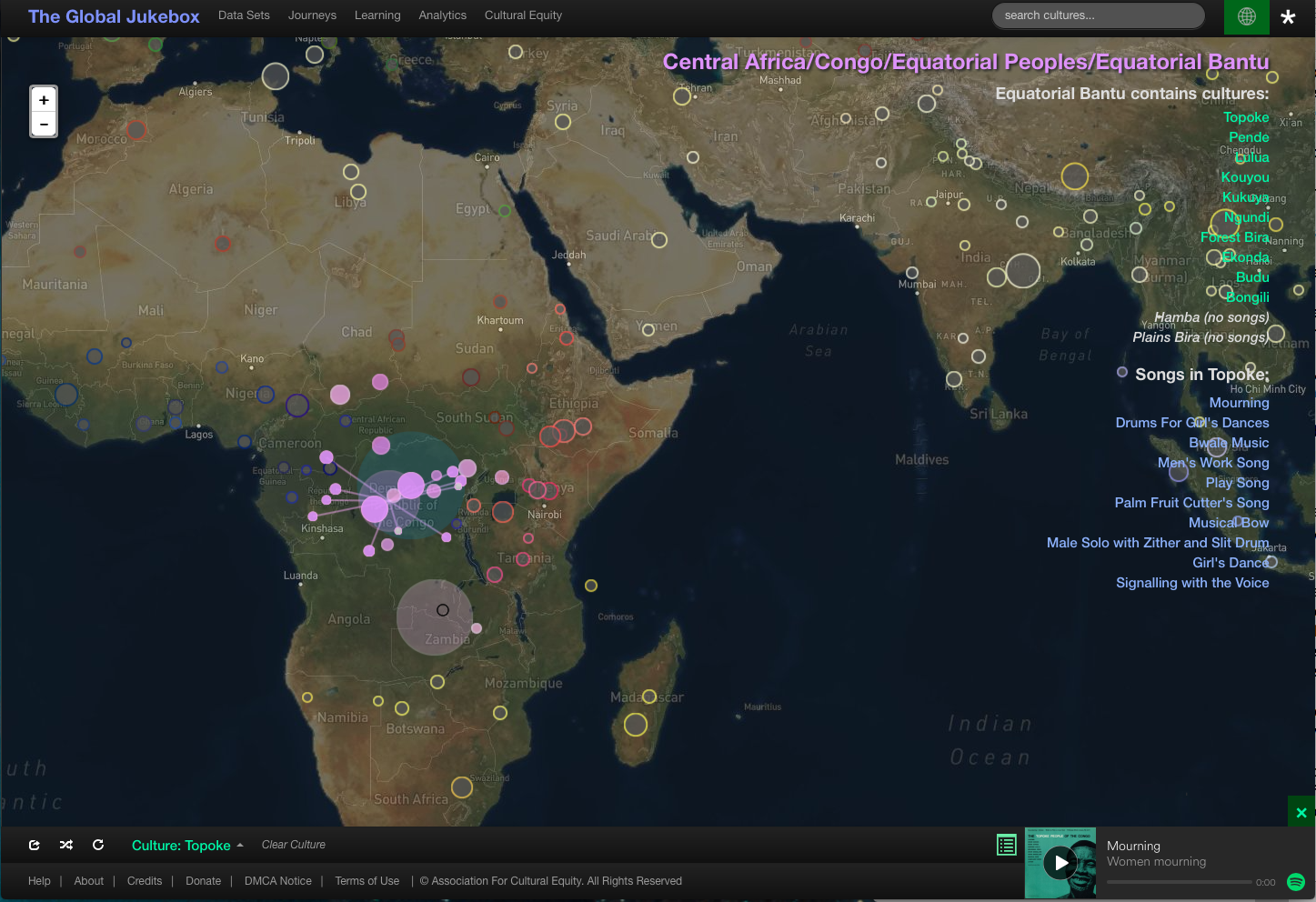

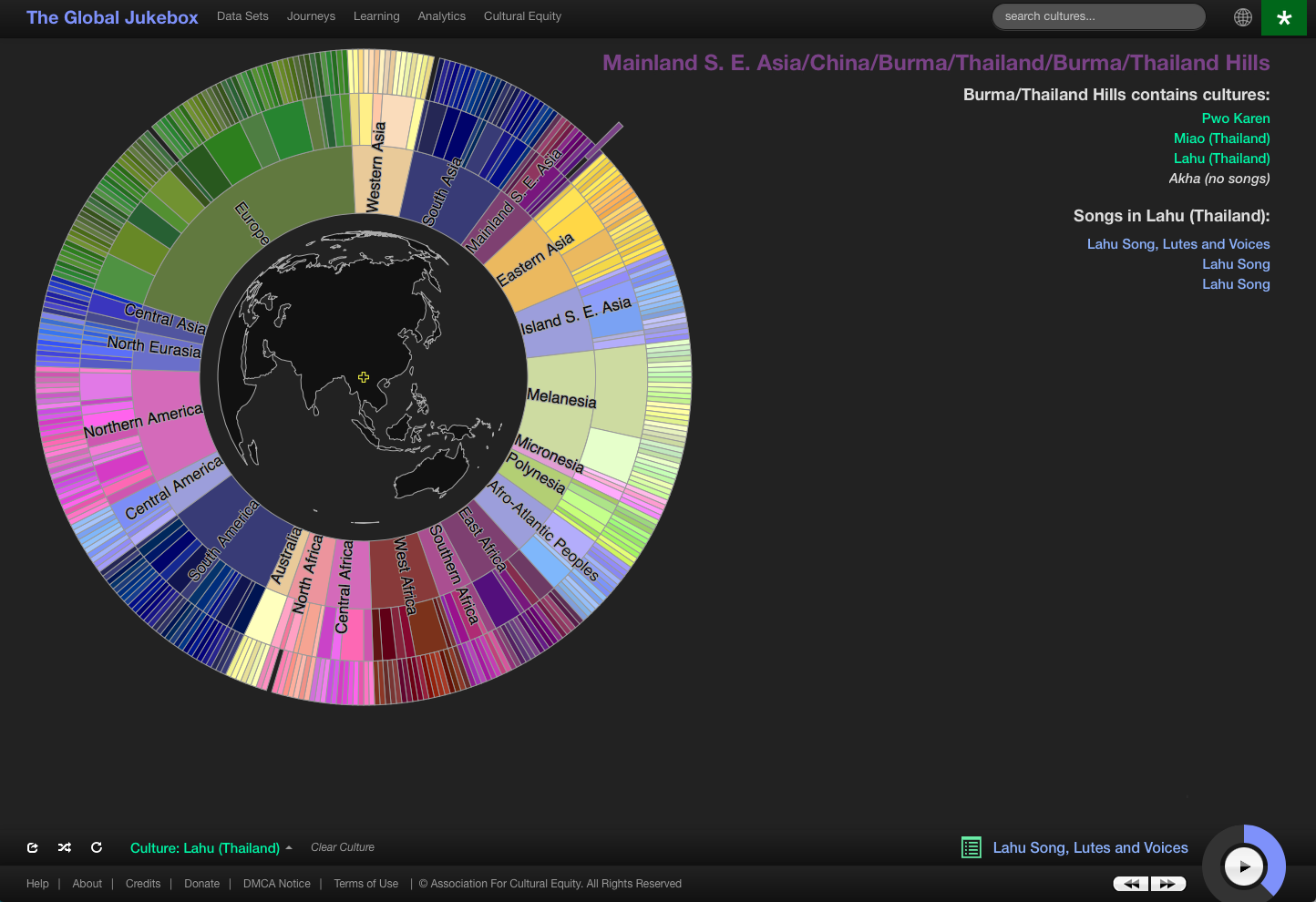

Since 1990, the Global Jukebox has functioned as a digital repository of music from Lomax’s global archive, as you can see in the very dated 1998 video above, featuring ACE director Gideon D’Arcangelo. Now, updated and put online, the newly-launched Global Jukebox web site provides an interactive interface, giving you access to detailed analyses of folk music from all over the world, and highly technical “descriptive data” for each song. You can learn the systems of “Choreometrics and Cantometrics”—specialized analytical tools for scientists—or you can casually browse the incredible diversity of music as a layperson, through a beautifully rendered map view or the colorfully attractive graphic “tree view,” below.

Stop by the Global Jukebox’s “About” page to learn much more about its technical specificities and history, which dates to 1960 when Lomax began working with anthropologist Conrad Arensberg at Columbia and Hunter Universities to study “the expressive arts” with scientific tools and emerging technologies. The Global Jukebox represents a highly schematic way of looking at Lomax’s body of work, and its ease of use and level of detail make it easy to leap around the world, sampling the thrilling variety of folk music he collected.

It is not, and is not meant as, a substitute for the living traditions Lomax helped safeguard, and the incredible music they have inspired professional and amateur musicians to make over the years. But the Global Jukebox gives us several unique ways of organizing and discovering those traditions—ways that are still evolving, such as a coming function for building your own cultural family tree with a playlist of songs from your musical ancestry.

Related Content:

Hear 17,000+ Traditional Folk & Blues Songs Curated by the Great Musicologist Alan Lomax

Legendary Folklorist Alan Lomax: ‘The Land Where the Blues Began’

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness