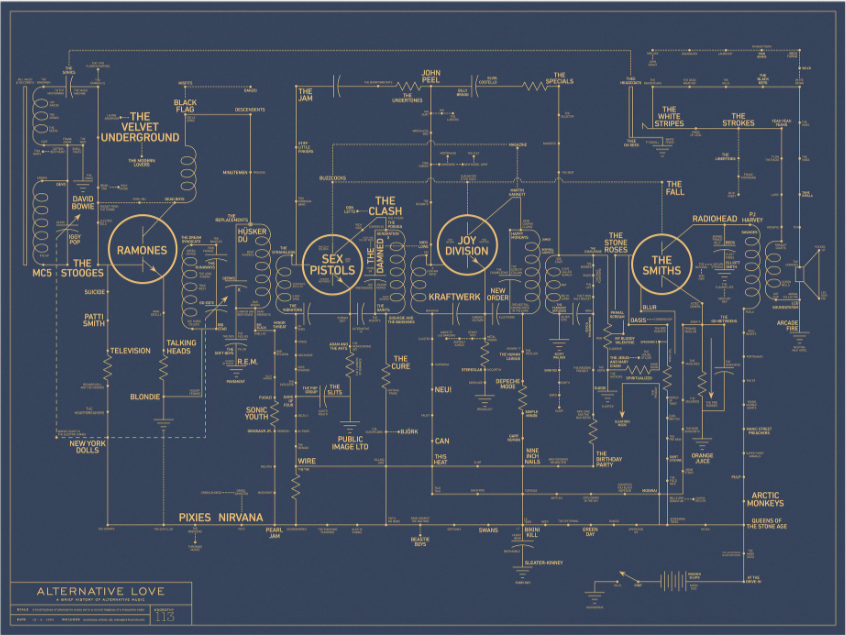

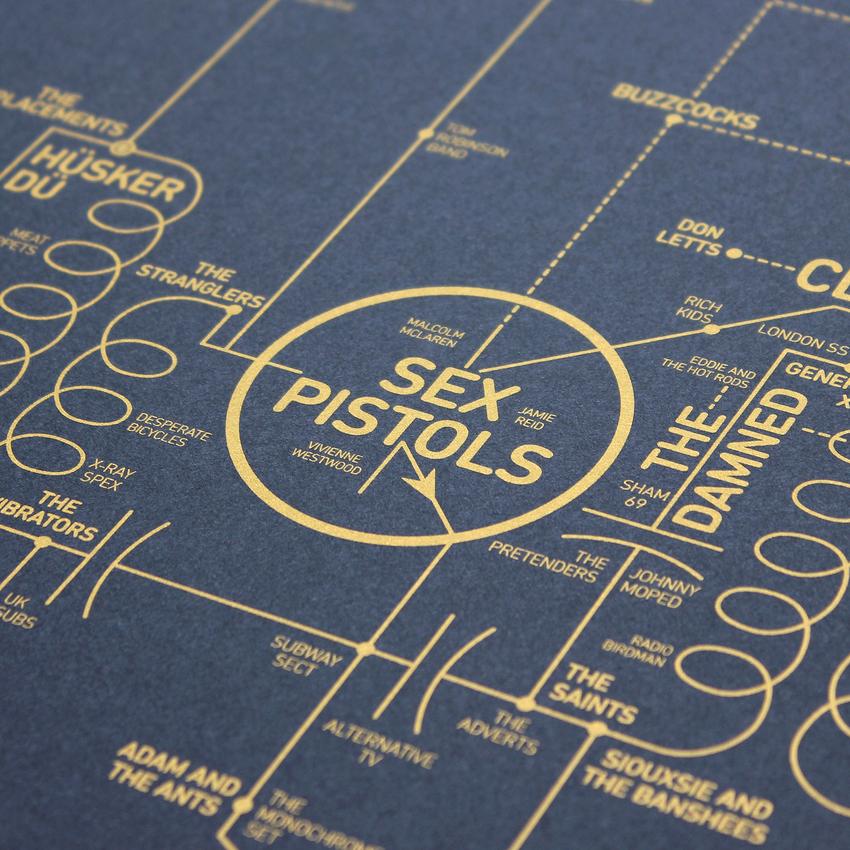

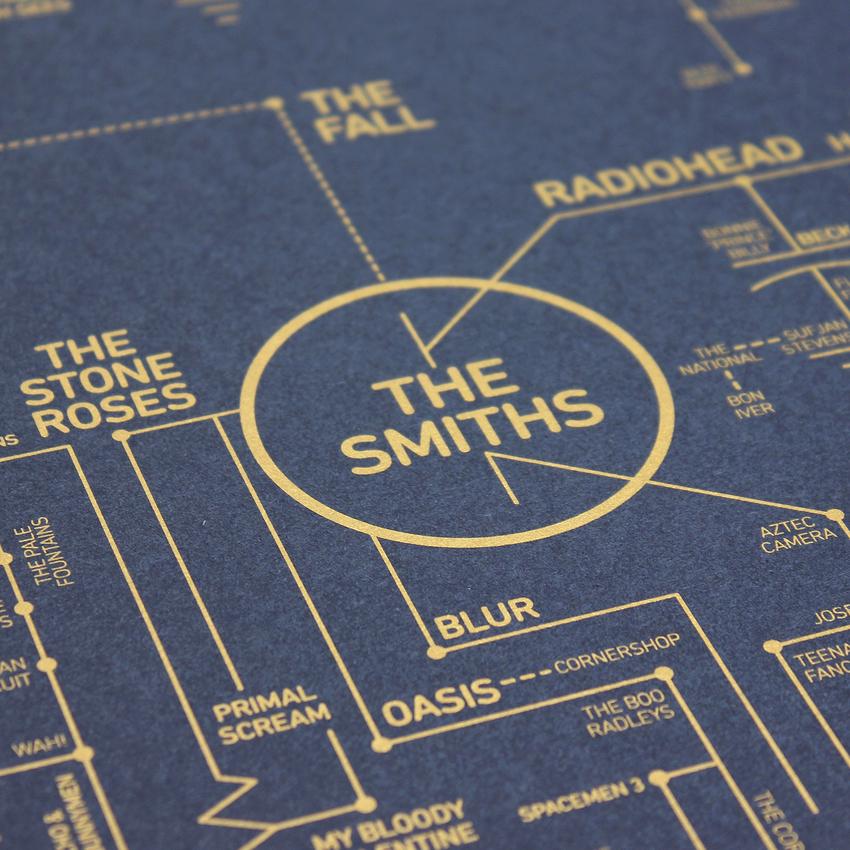

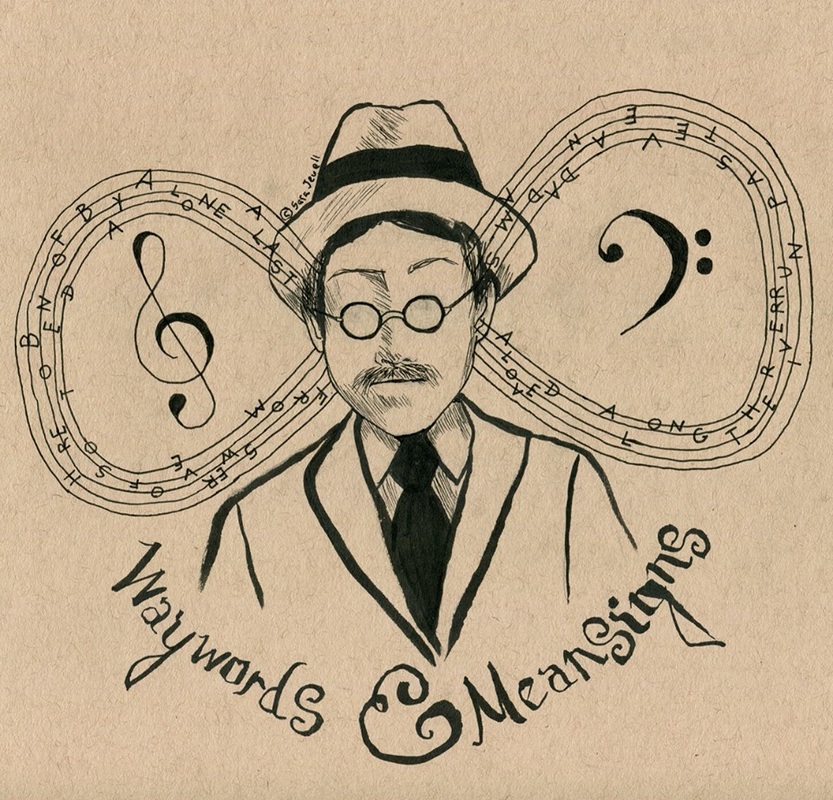

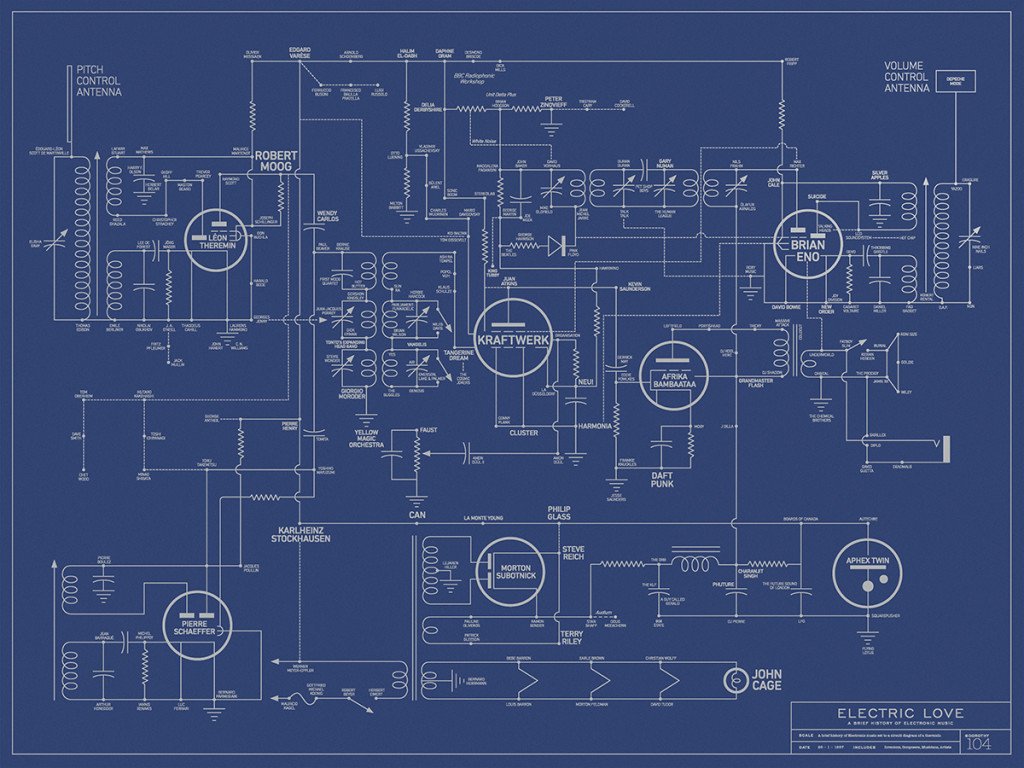

No historical leap forward has changed human culture more than the harnessing and commercialization of electricity. It may seem banal to point out such a truism—of course, nothing in the modern world would be what it is without the furious activity of Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla, and so many other inventors and early electrical engineers. But the scope of electricity’s role in the music of the past hundred plus years becomes truly awe-inspiring when we see it mapped out in the blueprint-like graphic above, “Electric Love,” inspired by circuit diagrams from the 1950s for a Theremin. (You can view the graphic in a larger, zoomable fashion here.)

As we noted in an earlier post, designer of “Electric Love” James Quail has created a similar diagram for Alternative and Indie rock, based on the circuit layout for a 1954 transistor radio. In the electronic music version here, not only does Quail draw on older technology, but he reaches back to earlier ancestors as well: to Edison, Alexander Graham Bell rival Elisha Gray, and Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville, inventor of the obscure early recording device the phonautograph.

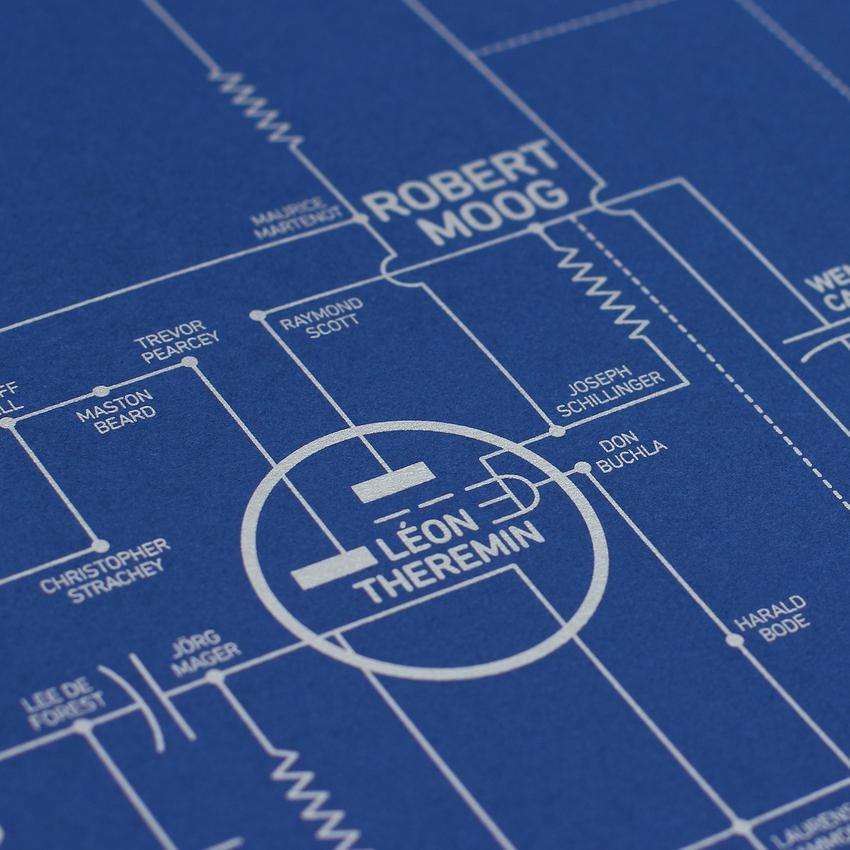

It’s a choice that foregrounds just how much technicians and engineers contributed directly to the sound of the modern world. Among them, of course, is the late Robert Moog, inventor of the portable analog synthesizer that become ubiquitous in nearly every genre of modern music, and whose work “was actually based,” notes Wired, “on technology from the 1800s.”

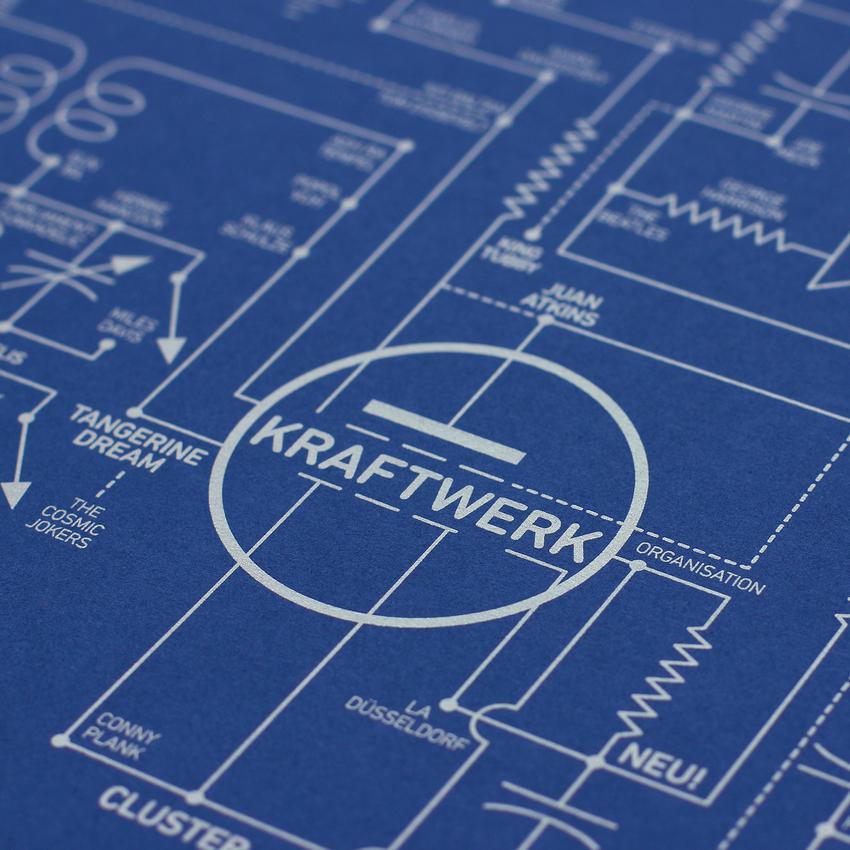

When it comes to the musicians who took this technology and transformed it into avant-gardism and dance records, the relationships are complex and perhaps impossible to fully represent in simple terms given the number of indirect influences through sampling technology. But “Electric Love” does an admirable job of showing how diffuse and diverse the music made by analog and digital technology has been. From the musique concrete of Pierre Schaffer, the experimentalism of Karlheinz Stockhausen and Arnold Schoenberg, commercial avant-garde of Delia Derbyshire and Wendy Carlos, minimalism of Steve Reich and Philip Glass, new wave of Kraftwerk, house and hip hop of Derrick May, Afrika Bambaataa and Kool DJ Herc, ambient soundscapes of Brian Eno, jittery electronica of Aphex Twin, synthpop of Depeche Mode and New Order…

It’s seemingly all there, and everything in-between, connected, Quail says, according to “common link[s]—whether that’s a style, or an instrument, or an influence on one another.” Even The Beatles and Pink Floyd show up, presumably for their creative studio experiments. On the whole, however, most of the smaller names here are much less familiar by comparison to Quail’s Alternative chart, but for true fans of electronic music, this only means there’s more to discover in this visual compendium of “over 200 inventors, innovators, artists, composers and musicians.” You can purchase “Electric Love” as a print from design house Dorothy.

Related Content:

The History of Electronic Music in 476 Tracks (1937–2001)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness