Note: If the video plays and you don’t hear sound, look for the volume control in the lower right hand corner of the video.

Within months of moving to London in autumn of 1966, Jimi Hendrix found himself a band, recorded a single, got himself a longterm girlfriend, and proceeded to take the UK by storm. His gigs were essential viewing by rock’s then-royalty–the Who, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Cream, all made sure they caught the American wonder. By the end of the year his first single “Hey Joe” landed him on British television and in the Top 10.

The above video is the first known footage of a live Jimi Hendrix Experience, though the band had been gigging for months. It takes place at the Chelmsford Corn Exchange, in the City of Chelmsford, about 50 miles north-east of London. The date is February 25, 1967, and the gig had only been advertised in the paper two days before (where he was listed as “Jimi Hendric”). As you can see, that’s all it took to fill this old traders building-turned-rock venue to the rafters.

The footage was shot for “Telixer: A Thing of Beat Is a Joy Forever,” a documentary on the current British music scene made for KRO, The Netherlands.

Hendrix and the band launch into Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone,” with a few ordinary opening bars setting up the guitar magic to follow. He then plays “Stone Free,” the b‑side of “Hey Joe.” You can see Pete Townshend and John Entwistle to the side of the stage, very briefly. The footage is intercut with shots of Swinging London and fashion hub Portobello Road, where it is said Hendrix bought his Hussars military jacket.

The website Chelmsford Rocks features a remembrance of that night from Shaun Everett, who was a Mod at the time and knew he had to make his way up on the train after work to catch Hendrix at the “Corn’ole,” as the youth called it.

Everett fills in the rest of the evening:

Hendrix gave two sets. That was the normal arrangement for the Corn’ole. Both sets usually 45 minutes to one hour each and there was absolutely no music to be had after 11.30pm…I have spent a long time looking for myself on that film clip but to no avail. I was probably still at the rear of the venue or even more likely in the local pub for the break!…Hendrix, at the end of the performance, walked straight up to a few of us standing just there and one of my mates lit his joint for him. They were so knocked out by that I recall. My recollection was more nasal. Rock musicians have this uncanny ability to harbour their own post-set aromas about themselves: in this case that unmistakeable aroma of cannabis…I will always remember that part even if my music recollections are a bit sparse. I have also ‘dined out’ on that anecdote for many years since. I had passed close by the ‘God’.

The Corn Exchange hosted many acts over its time as a music venue, including David Bowie and Pink Floyd. But in 1969, the city tore down the 19th century building, assuming something more accommodating for live music would be built in its place. That didn’t happen. On this page you can see the aftermath of the bulldozers, and a modern shot of the city street corner that added so much to rock history.

Related Content:

Jimi Hendrix Wreaks Havoc on the Lulu Show, Gets Banned From the BBC (1969)

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the artist interview-based FunkZone Podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.

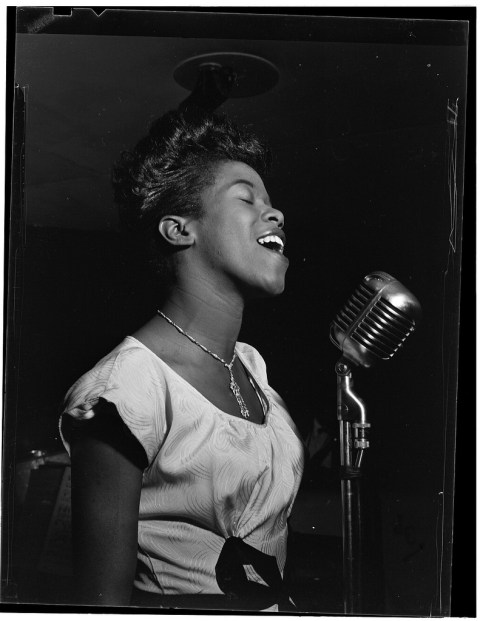

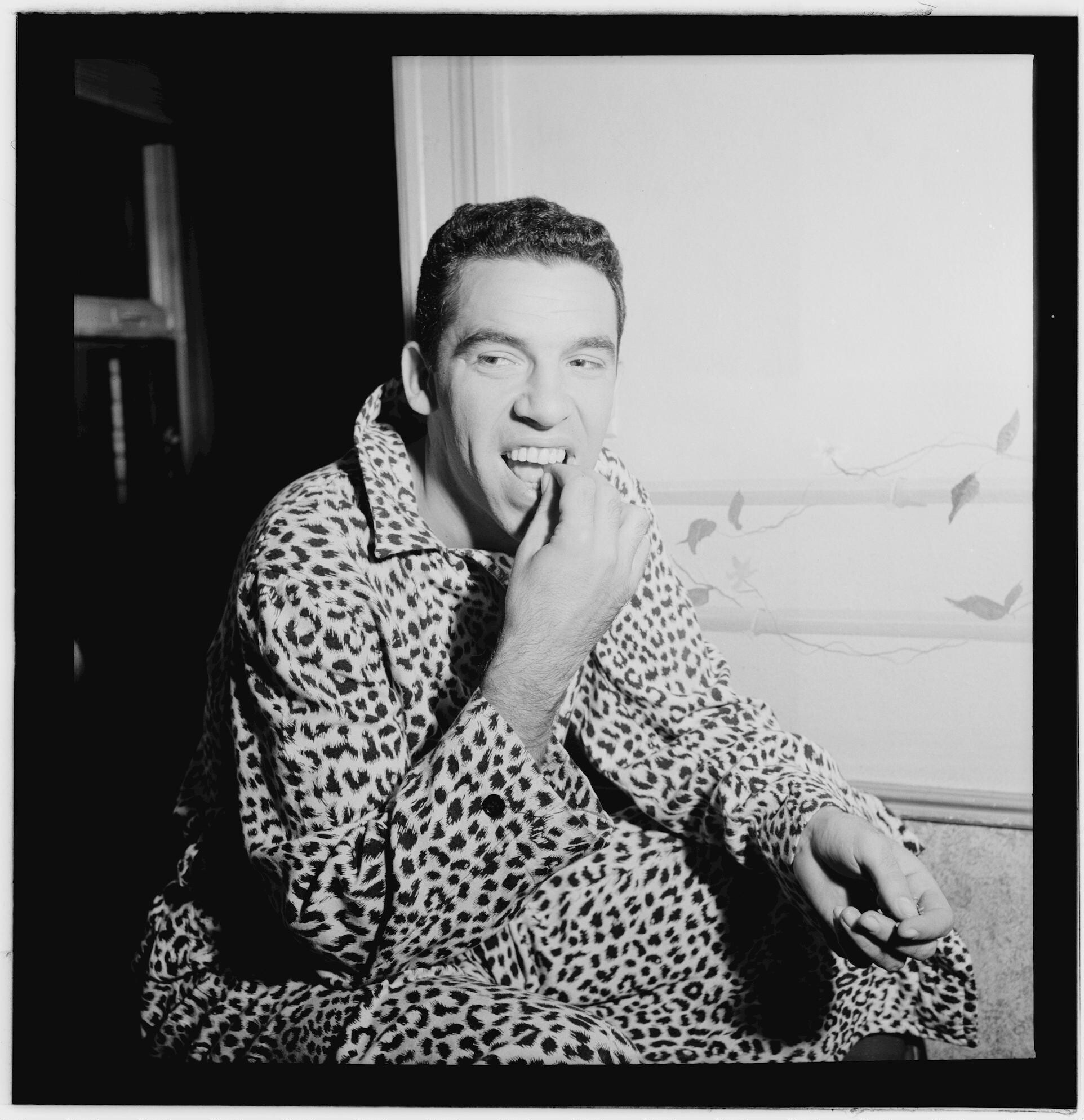

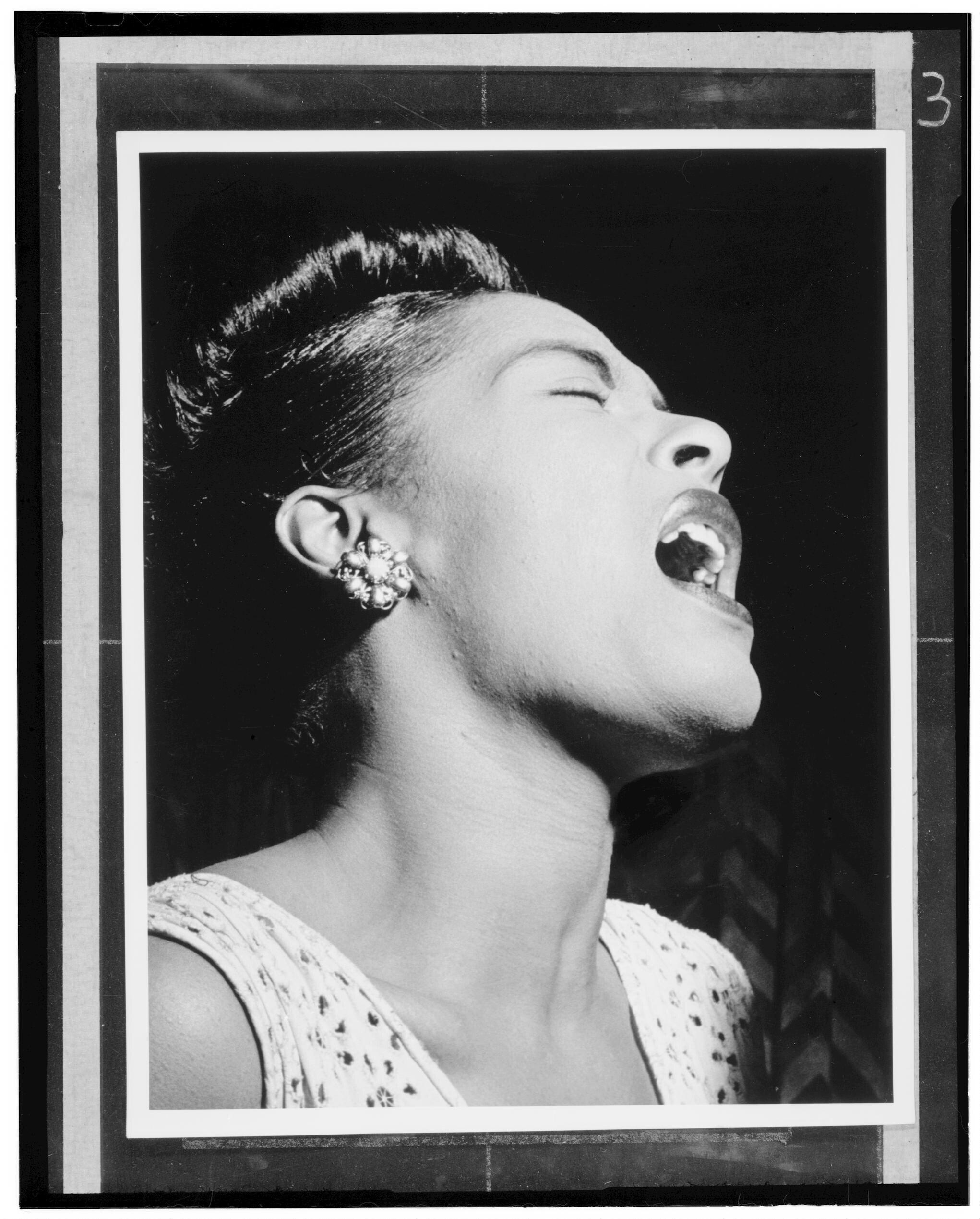

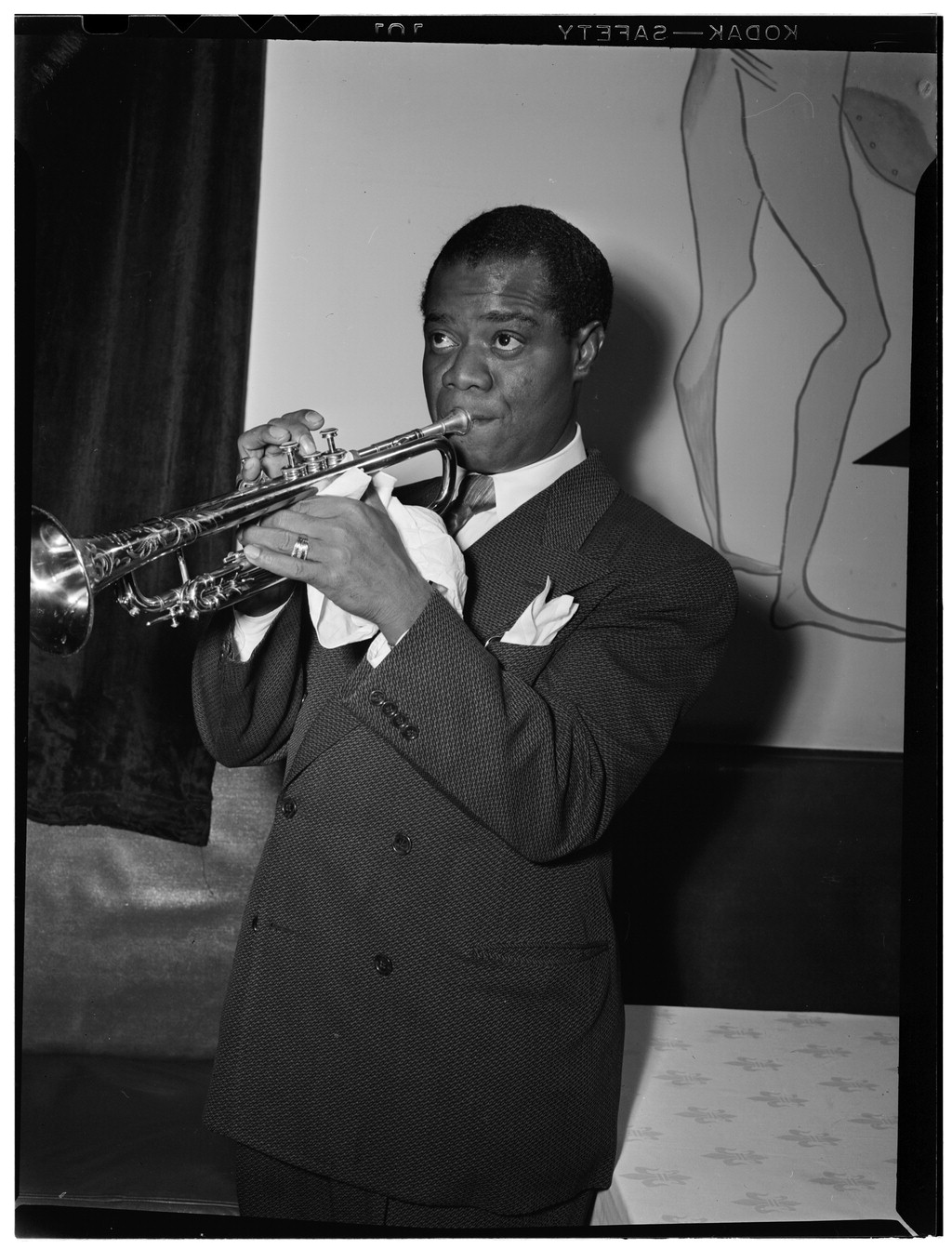

As Gottlieb once told The New York Times, “I got into photography because The Post was stingy and wouldn’t pay photographers to cover my 11 o’clock concerts.” But he developed an undeniably keen eye for performance.

As Gottlieb once told The New York Times, “I got into photography because The Post was stingy and wouldn’t pay photographers to cover my 11 o’clock concerts.” But he developed an undeniably keen eye for performance.