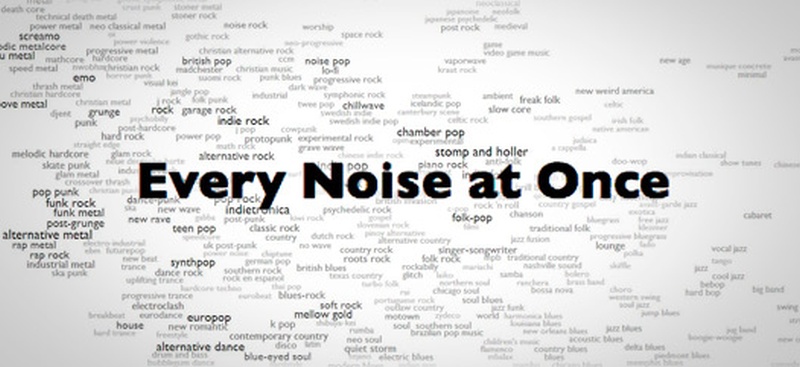

If you are ready for a time-suck internet experience that will also make you feel slightly old and out of step with the culture, feel free to dive into Every Noise at Once. A scatter-plot of over 1,530 musical genres sourced from Spotify’s lists and based on 35 million songs, Every Noise at Once is a bold attempt at musical taxonomy. The Every Noise at Once website was created by Glenn McDonald, and is an offshoot of his work at Echo Nest (acquired by Spotify in 2014).

McDonald explains his graph thus:

This is an ongoing attempt at an algorithmically-generated, readability-adjusted scatter-plot of the musical genre-space, based on data tracked and analyzed for 1,536 genres by Spotify. The calibration is fuzzy, but in general down is more organic, up is more mechanical and electric; left is denser and more atmospheric, right is spikier and bouncier.

It’s also egalitarian, with world dominating “rock-and-roll” given the same space and size as its neighbors choro (instrumental Brazilian popular music), cowboy-western (Conway Twitty, Merle Haggard, et. al.), and Indian folk (Asha Bhosle, for example). It also makes for some strange bedfellows: what factor does musique concrete share with “Christian relaxitive” other than “reasons my college roommate and I never got along.” Now you can find out!

Click on any of the genres and you’ll hear a sample of that music. Double click and you’ll be taken to a similar scatter-plot graph of its most popular artists, this time with font size denoting popularity and a similar sample of their music.

I’ve been spending most of my time exploring up in the top right corner where all sorts of electronic dance subgenres hang out. I’m not too sure what differentiates “deep tech house” from “deep deep house” or “deep minimal techno” or “tech house” or even “deep melodic euro house” but I now know where to come for a refresher course.

Spotify and other services depend on algorithms and taxonomies like this to deliver consistent listening experiences to its users, and they were attracted to Echo Nest for its work with genres. Echo Nest was originally based on the dissertation work of Tristan Jehan and Brian Whitman at the MIT Media Lab, who over a decade ago were trying to understand the “fingerprints” of recorded music. Now when you listen to Spotify’s personalized playlists, Echo Nest’s research is the engine working in the background.

McDonald says in this 2014 Daily Dot article this isn’t about a machine guessing our taste.

“No, the machines don’t know us better than we do. But they can very easily know more than we do. My job is not to tell you what to listen to, or to pass judgment on things or ‘make taste.’ It’s to help you explore and discover. Your taste is your business. Understanding your taste and situating it in some intelligible context is my business.”

If you’d like a more passive journey through the ever expanding music genre universe, there’s a Spotify playlist of one song from each genre (all 1,500+) above. See you in the deep, deep house!

via Kottke.org

Related Content:

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the FunkZone Podcast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.