One wonders what might have become of Richard Atkins’ musical career had he come of age in this millennium, when youngsters suffering from acute stage fright regularly attract stadium-sized followings on Youtube.

This was most definitely not the case in 1968, when Atkins, aged 19, took the stage in a small Hollywood club filled with music industry brass, there specifically to see him.

Unfortunately, talent could only take him so far. Having learned to play guitar only a couple of years earlier in the wake of a disfiguring motorcycle accident, he and partner Richard Manning had recorded an album, Richard Twice, for Mercury Records. The presence on that record of several members of the Wrecking Crew, an informal, but legendary group of LA session musicians, conferred extra pop pedigree. The Acid Archives later called it “a virtually perfect pop album, the kind of thing that would have ruled the charts if the wind had been blowing the right way that month.”

Alas, one tiny technical difficulty at the start of the gig caused Manning to flee, leaving the freaked out and frighteningly ill equipped Atkins to deal with the yawning chasm that had opened between him and the audience. The only fix that occurred to him was a Bugs Bunny-inspired soft shoe, a move that apparently went over big with his Mom, prior to the accident, when he had two legs and could balance without a crutch.

As recounted in Matthew Salton’s animated documentary, above, this soul crushing moment is not without humor. Atkins, affably narrating his own story, has had 50 years to mull that night over, and realizes that blown opportunities are probably more universal than successfully snagged brass rings (American Idol, anyone?)

Over the ensuing years, Atkins found fulfillment as a woodworker and family man, but music remained a painful what-if, addressed largely through avoidance.

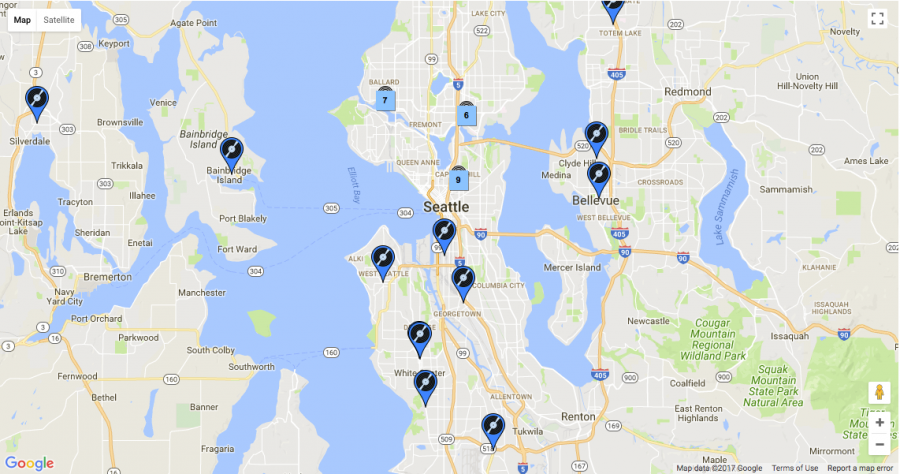

Salton’s exuberantly scratchy animation comes as Atkins is taking steps to conquer his stage fright, performing out at small cafes, festivals, and potluck suppers near his Pacific Northwest home.

He’s been posting old songs, gently reminding listeners, “before I’m judged too harshly, remember that I was 18 and living in North Hollywood, probably raging hormones and in the music business to boot!”

He’s also writing and sharing new songs, including the touching “Life Is A Rollercoaster,” above.

Performing on Facebook Live in conjunction with Salton’s New York Times Op-Doc essay, he tears up when the interviewer informs him that his daughter has just posted an encouraging comment, and eagerly confirms his availability when another commenter asks if he’d be up for a gig.

It’s only too late when you’re in the grave.

Travel back in time with a couple more psych-folk cuts from Richard Twice, above, or buy the album in digital form on Amazon.

Related Content:

Syd Barrett’s “Effervescing Elephant” Comes to Life in a New Retro-Style Animation

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.