There has maybe never been a better time to critically examine the granting of special privileges to people for their talent, personality, or wealth. Yet, for all the harm wrought by fame, there have always been celebrities who use the power for good. The twentieth century is full of such figures, men and women of conscience like Muhamad Ali, Nina Simone, and Paul Robeson—extraordinary people who lived extraordinary lives. Yet no celebrity activist, past or present, has lived a life as extraordinary as Josephine Baker’s.

Born Freda Josephine McDonald in 1906 to parents who worked as entertainers in St. Louis, Baker’s early years were marked by extreme poverty. “By the time young Freda was a teenager,” writes Joanne Griffith at the BBC, “she was living on the streets and surviving on food scraps from bins.” Like every rags-to-riches story, Baker’s turns on a chance discovery. While performing on the streets at 15, she attracted the attention of a touring St. Louis vaudeville company, and soon found enormous success in New York, in the chorus lines of a string of Broadway hits.

Baker became professionally known, her adopted son Jean-Claude Baker writes in his biography, as “the highest-paid chorus girl in vaudeville.” A great achievement in and of itself, but then she was discovered again at age 19 by a Parisian recruiter who offered her a lucrative spot in a French all-black revue. “Baker headed to France and never looked back,” parlaying her nearly-nude danse sauvage into international fame and fortune. Topless, or nearly so, and wearing a skirt made from fake bananas, Baker used stereotypes to her advantage—by giving audiences what they wanted, she achieved what few other black women of the time ever could: personal autonomy and independent wealth, which she consistently used to aid and empower others.

Throughout the 20s, she remained an archetypal symbol of jazz-age art and entertainment for her Folies Bergère performances (see her dance the Charleston and make comic faces in 1926 in the looped video above). In 1934, Baker made her second film Zouzou (top), and became the first black woman to star in a major motion picture. But her sly performance of a very European idea of African-ness did not go over well in the U.S., and the country she had left to escape racial animus bared its teeth in hostile receptions and nasty reviews of her star Broadway performance in the 1936 Ziegfeld Follies (a critic at Time referred to her as a “Negro wench”). Baker turned away from America and became a French citizen in 1937.

American racism had no effect on Baker’s status as an international superstar—for a time perhaps the most famous woman of her age and “one of the most popular and highest-paid performers in Europe.” She inspired modern artists like Picasso, Hemingway, E.E. Cummings, and Alexander Calder (who sculpted her in wire). When the war broke out, she hastened to work for the Red Cross, entertaining troops in Africa and the Middle East and touring Europe and South America. During this time, she also worked as a spy for the French Resistance, transmitting messages written in invisible ink on her sheet music.

Her massive celebrity turned out to be the perfect cover, and she often “relayed information,” the Spy Museum writes, “that she gleaned from conversations she overheard between German officers attending her performances.” She became a lieutenant in the Free French Air Force and for her efforts was awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Medal of the Resistance by Charles De Gaulle and lauded by George S. Patton. Nonetheless, many in her home country continued to treat her with contempt. When she returned to the U.S. in 1951, she entertained huge crowds, and dealt with segregation “head –on,” writes Griffith, refusing “to perform in venues that would not allow a racially mixed audience, even in the deeply divided South.” She became the first person to desegregate the Vegas casinos.

But she was also “refused admission to a number of hotels and restaurants.” In 1951, when employees at New York’s Stork Club refused to serve her, she charged the owner with discrimination. The Stork club incident won her the lifelong admiration and friendship of Grace Kelly, but the government decided to revoke her right to perform in the U.S., and she ended up on an FBI watch list as a suspected communist—a pejorative label applied, as you can see from this declassified 1960 FBI report, with extreme prejudice and the presumption that fighting racism was by default “un-American.” Baker returned to Europe, where she remained a superstar (see her perform a medley above in 1955).

She also began to assemble her infamous “Rainbow Tribe,” twelve children adopted from all over the world and raised in a 15th-century chateau in the South of France, an experiment to prove that racial harmony was possible. She charged tourists money to watch the children sing and play, a “little-known chapter in Baker’s life” that is also “an uncomfortable one,” Rebecca Onion notes at Slate. Her estate functioned as a “theme park,” writes scholar Matthew Pratt Guterl, a “Disneyland-in-the-Dordogne, with its castle in the center, its massive swimming pool built in the shape of a “J” for its owner, its bathrooms decorated like an Arpège perfume bottle, its hotels, its performances, and its pageantry.” These trappings, along with a menagerie of exotic pets, make us think of modern celebrity pageantry.

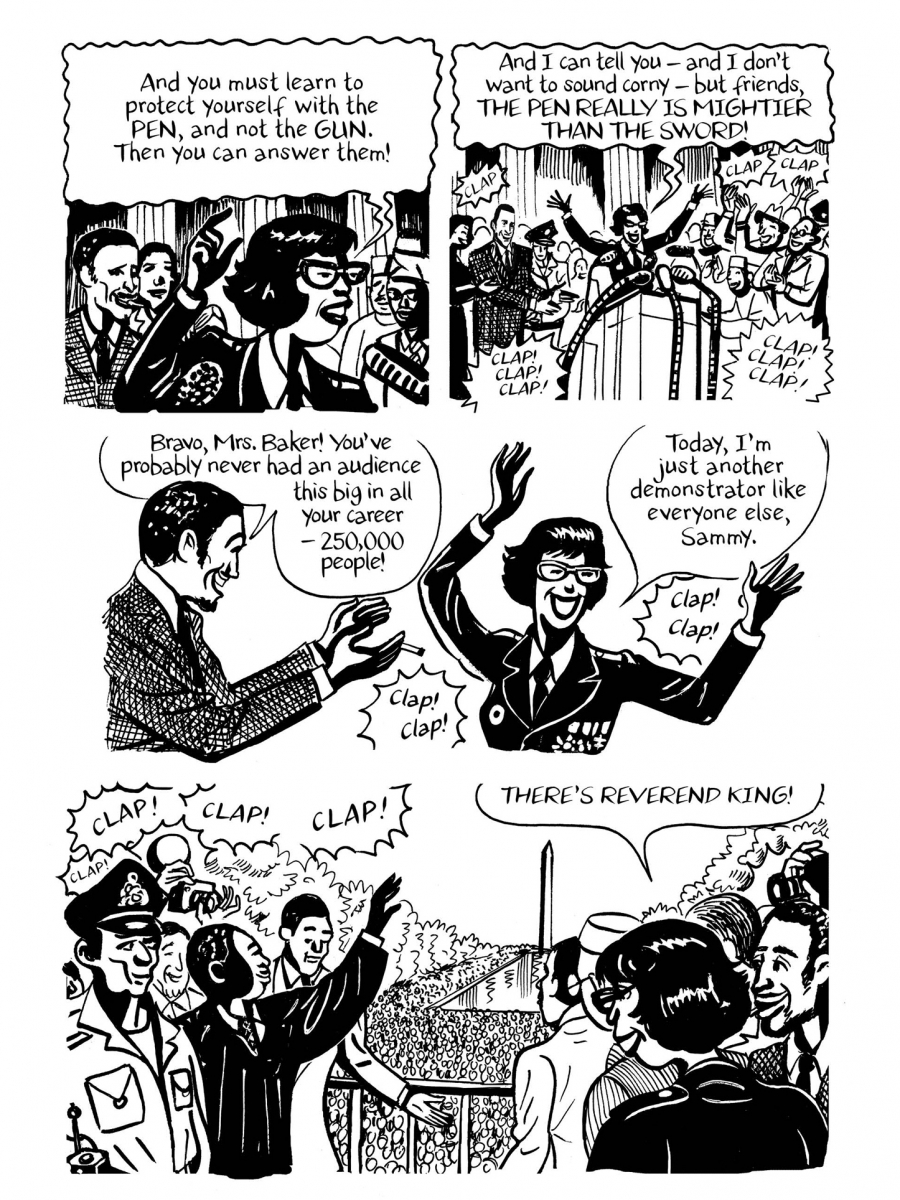

But for all its strange excesses, Guturl maintains, her “idiosyncratic project was in lockstep with the mainstream Civil Rights Movement.” She wouldn’t return to the States until 1963, with the help of Attorney General Robert Kennedy, and when she did, it was as a guest of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the organizers of the March on Washington, where, in her Free French Air Force uniform, she became the only woman to address the crowd. The visual recounting of that moment above comes from a new 600-page graphic biography that follows Baker’s “trajectory from child servant in St. Louis,” PRI writes, “to her days as a vaudeville performer, a major star in France, and later, a member of the French Resistance and an American civil rights activist.”

In her speech, she directly confronted the government who had turned her into an enemy:

They thought they could smear me, and the best way to do that was to call me a communist. And you know, too, what that meant. Those were dreaded words in those days, and I want to tell you also that I was hounded by the government agencies in America, and there was never one ounce of proof that I was a communist. But they were mad. They were mad because I told the truth. And the truth was that all I wanted was a cup of coffee. But I wanted that cup of coffee where I wanted to drink it, and I had the money to pay for it, so why shouldn’t I have it where I wanted it?

Baker made no apologies for her wealth and fame, but she also took every opportunity, even if misguided at times, to use her social and financial capital to better the lives of others. Her plain-speaking demands opened doors not only for performers, but for ordinary people who could look to her as an example of courage and grace under pressure into the 1970s. She continued to perform until her death in 1975. Just below, you can see rehearsal footage and interviews from her final performance, a sold-out retrospective.

The opening night audience included Sophia Lauren, Mick Jagger, Shirley Bassey, Diana Ross, and Liza Minelli. Four days after the show closed, Baker was found dead in her bed at age 68, surrounded by rave reviews of her performance. Her own assessment of her five-decade career was distinctly modest. Earlier that year, Baker told Ebony magazine, “I have never really been a great artist. I have been a human being that has loved art, which is not the same thing. But I have loved and believed in art and the idea of universal brotherhood so much, that I have put everything I have into them, and I have been blessed.” We might not agree with her critical self-evaluation, but her life bears out the strength and authenticity of her convictions.

Related Content:

Women of Jazz: Stream a Playlist of 91 Recordings by Great Female Jazz Musicians

James Baldwin Bests William F. Buckley in 1965 Debate at Cambridge University

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness