The Beatles have seemingly never been just a band; they’ve been a brand, a history, an institution, a genre, a generational soundtrack, a merchandising empire, and so much more—possessed of the kind of cultural importance that makes it impossible to think of them as only musicians. Their “narrative arc,” Tom Ewing writes at Pitchfork, from Beatlemania to their current enshrinement and everything in-between, “is irresistible.” But the story of the Beatles as we typically understand it, Ewing writes, does their music a disservice, setting it apart from “the rest of the pop world” and “making newcomers as resentful as curious.”

For all the deification (which John Lennon scandalously summed up in his “bigger than Jesus” quip), the band began as nothing particularly out of the ordinary. “Britain in the early 1960s swarmed with rock’n’roll bands,” and though the Beatles excelled early on, they mostly followed trends, they didn’t invent them.

Their sound was so of the time that Decca’s A&R executive Dick Rowe passed on them in 1962, telling Brian Epstein, “guitar groups are on their way out.” Little could he have known, however: “guitar groups” came roaring back because of the band’s first album, Please, Please Me, and the especially savvy marketing skills of Epstein, who helped land them that fateful Ed Sullivan Show appearance.

Millions of people saw them play their single “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and the world changed forever, so the story goes. In so many ways that’s so. The Ed Sullivan gig launched a thousand bands, and remains at top of the list of nearly every baby boomer musician’s most influential moments. But as the sixties wore on, and Beatlemania assumed the various forms of lunchboxes, fan clubs, and a wacky cartoon series with badly impersonated voices, their act seemed like it might run its course as a passing pop-culture fad. They were, in effect, a very talented boy band, subject to the fate of boy bands everywhere. Their ascent into Olympus wasn’t inevitable, and “every record they made was born out of a new set of challenges.”

Rubber Soul, the band’s 1965 farewell to the carefree, boyish pop band they had been, perfectly met the challenge they faced—how to grow up. It was “the most out-there music they’d ever made, but also their warmest, friendliest and most emotionally direct,” Rob Sheffield writes at Rolling Stone. They were “smoking loads of weed, so all through these songs, wild humor and deep emotion go hand in hand.” These threads of playful, drug-fueled experimentation, screwball comedy, and earnest sentiment changed not only the band’s career trajectory, but “cut the story of pop music in half,” Sheffield opines.

Such proclamations can and have been made of the groundbreaking Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Each Beatles milestone cements our impression of them as a messianic force, destined to steer the course of pop music history—a story that glosses over their novelty records, lesser works, many outtakes and half thoughts, cover songs, and flops, like their 1967 Magical Mystery Tour film. Some of these lesser works deserve the label. The mellotron-heavy “Only a Northern Song” on Yellow Submarine, for example, sounds far too much like an inferior “Strawberry Fields Forever.”

Others, like the Magical Mystery Tour soundtrack album, give us gems like McCartney’s “Penny Lane” (a song originally recorded during the Sgt. Pepper’s sessions), as well as “I Am the Walrus,” “Hello Goodbye,” “Baby, You’re a Rich Man,” “All You Need is Love” … the film may have disappointed, but the record, I’d say, is essential.

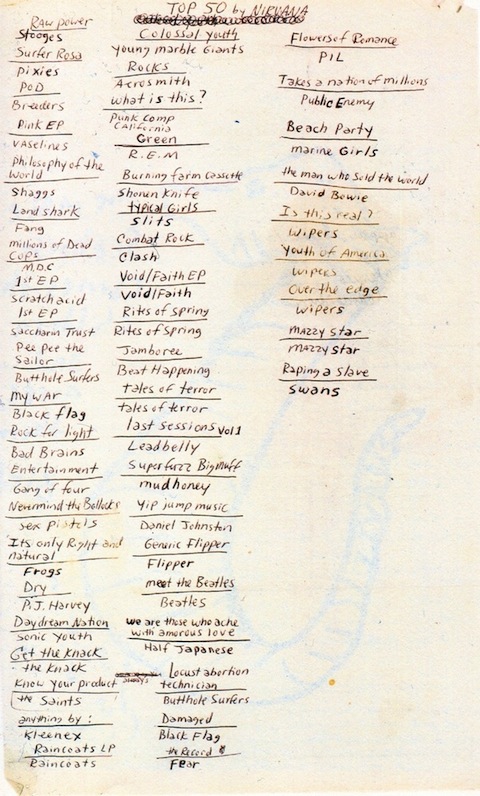

In the chronological Spotify playlist further up of 338 songs, you can follow the quirky, upbeat, downbeat, sometimes uneven, sometimes breathtakingly brilliant musical journey of the band everyone thinks they know and see why they are so much more interesting than a museum exhibit or rock and roll mythology. They were, after all, only human, but their willingness to indulge in weird experiments and to master genre exercises gave them the discipline and experience they needed to make their masterpieces.

Related Content:

How The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band Changed Album Cover Design Forever

Watch HD Versions of The Beatles’ Pioneering Music Videos: “Hey Jude,” “Penny Lane,” “Revolution” & More

Hear the 1962 Beatles Demo that Decca Rejected: “Guitar Groups are on Their Way Out, Mr. Epstein”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness