To the naked eye — or at least to the naked eye of anyone born after about 1990 — fans of the Grateful Dead and fans of Steely Dan may look basically the same. Both bands emerged from the 1960s-forged counterculture of America’s “Baby Boom” generation, broadly defined, and both have drawn unusually dedicated listenerships. Yet few bodies of musical work could project such different sets of artistic sensibilities: on one side Steely Dan has the handful of meticulously recorded studio albums filled with esoteric wisecracks and literary references, and on the other the Grateful Dead has the vast archives of live performance heavy on both extended improvisations and good vibes.

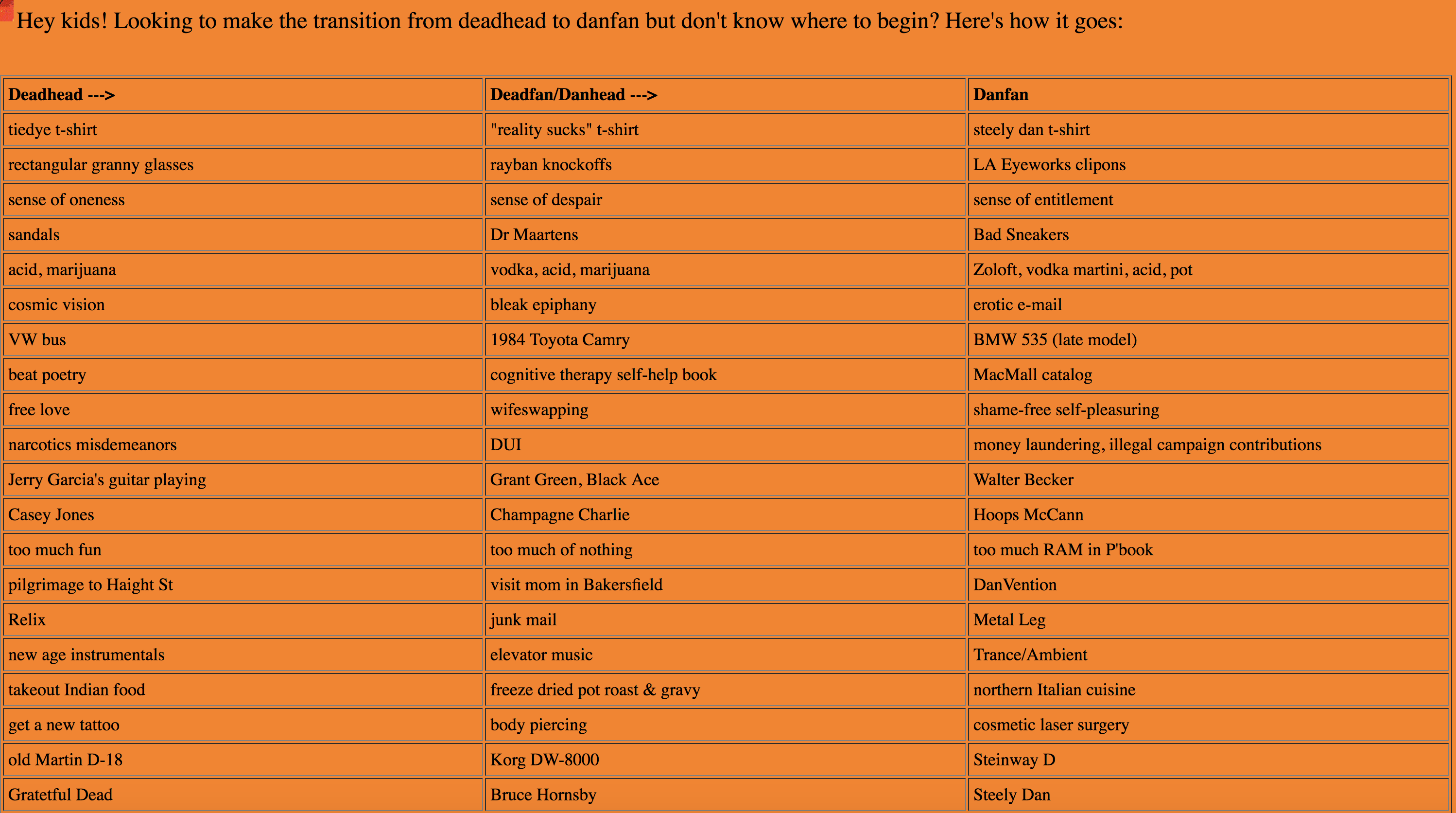

Close inspection reveals that the deeper differences in the music of the Grateful Dead and Steely Dan also manifest in the lifestyles of “Deadheads” and “Danfans.” You can see how in this handy Deadhead/Danfan Conversion Chart available on Steely Dan’s official site. (View it in a larger format here.) Where the accoutrements of the Grateful Dead’s crowd include granny glasses, VW buses, and tattooing, it shows us, Steely Dan’s has its LA Eyeworks clip-ons, BMW 353s, and cosmetic laser surgery.

Deadheads read beat poetry, receive cosmic visions, and enjoy the guitar playing of the late Jerry Garcia; Danfans read the MacMall catalog, send erotic e‑mails, and enjoy the guitar playing of the late Walter Becker (among that of the dozens of other professionals called into the studio).

The Deadhead/Danfan Conversion Chart also includes a middle column describing the transitional stage separating Deadhead from Danfan. Between the Grateful Dead fan’s sense of oneness and the Steely Dan fan’s sense of entitlement comes a sense of despair; between the Deadhead’s takeout Indian food and the Danfan’s northern Italian cuisine comes freeze-dried pot roast and gravy. Laid out in this way, the journey from the Grateful Dead to Steely Dan mirrors the life journey taken by many a Baby Boomer: from blissed-out utopianism, consciousness-expanding substances, and free love to creative cynicism, antidepressants, and high-end personal electronics. Or perhaps, to use a metaphor popular in 1960s America, the yin of the Deadhead and the yang of the Danfan inhabits us all, regardless of generation.

Click here to view the Deadhead/Danfan Conversion Chart.

Related Content:

How Steely Dan Wrote “Deacon Blues,” the Song Audiophiles Use to Test High-End Stereos

11,215 Free Grateful Dead Concert Recordings in the Internet Archive

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.