Does it make sense to call Glenn Gould, that most prodigious and unusual interpreter of classical piano, a composer? While his radio documentary trilogy should earn him the title, his classical performances and recordings remain bound—albeit sometimes maddeningly loosely for certain tastes—to the work of others, whether Mozart, Schoenberg, Strauss, Sibelius, Beethoven, Brahms, or J.S. Bach, who provided Gould with the material that would launch his career, the “Goldberg” Variations, which he first recorded at 22 in 1955 to widespread acclaim and admiration. His debut became one of the best-selling classical albums of all time.

Famously Gould made another recording of the “Goldberg” in 1981, the year before his early death at 50, “leaving the two Bach statements as bookends to his career,” writes Michael Cooper at The New York Times. Gould revered the composers he recorded and expounded on their virtues at length in written, televised, and broadcast commentaries. This was especially the case with Bach, whom he described as “first and last an architect, a constructor of sound, and what makes him so inestimably valuable to us is that he was beyond a doubt the greatest architect of sound who ever lived.”

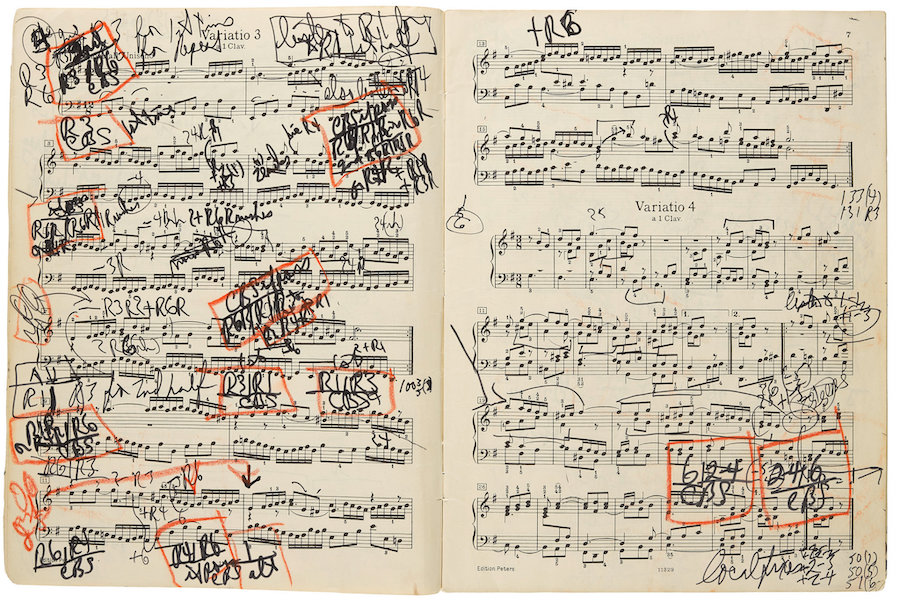

The Canadian pianist was more than content to devote his life to others’ constructions of sound, rather than trying his hand at writing them himself, but if Bach was an architect of sound, we might compare Gould to a director—a meticulous auteur with a singular and solitary vision. Take his heavily marked up score for the 1981 “Goldberg,” above, recently resurfaced and destined for auction on December 5th at Bonhams in New York. “I would call this the equivalent of a shooting script of a movie,” comments critic and University of Southern California professor Tim Page.

Gould chose the studio over live performance early in his career, finding that the controlled experience of recording—the ability to do multiple takes and edit them together in a kind of narrative dynamic—provided him with maximum creative freedom. His 1981 “Goldberg,” “electrified the classical music world nearly as much as his classic 1955 recording had,” writes pianist Anthony Tommasini. His recordings resonate far outside the classical world, such that a Toronto hip-hop producer has even remixed his work.

There is another case for thinking of Gould himself as something of a modern producer/remixer—of other composers’ works and of his own performances. Page, who knew Gould well, speculates that he would have loved the internet. “I bet, without any interference,” he says, “Glenn would have recorded three or four different versions of the same piece and put them all out there for people to listen to and even chose from.” He took to modern techniques and technologies without reservation.

Gould’s friendliness to modernity, and its enthusiastic embrace of him, makes him seem like so much more than a pianist, and of course, he was. But we should also consider him—and all great classical interpreters—as at least a co-composer, a role as old as classical music itself. As pianist Jeremy Denk writes, each score is “at once a book and a book waiting to be written.” (Tommasini points out that “Bach’s scores leave much to the choices and tastes of performers,” and in the case of “Goldberg,” we have only reconstructions of the original.) The Variations, after all, are not named for Bach, but for virtuoso harpsichordist Johann Gottlieb Goldberg, likely the original performer of the piece.

The particularly idiosyncratic approach of a pianist like Gould, writes Denk, with much ambivalence, “found perversity in the music and teased it out, but mostly he just slathered it on; piece after piece, he made brilliant but deeply unintuitive, ‘unnatural’ choices, and made them work through sheer force of will.” Now, in his 1981 “Goldberg” score, fans and scholars can see for themselves how much deliberation was involved in his apparent willfulness.

In Gould’s interpretations, we cannot separate the player from the work. “He immortalized his phobias,” his passions, and his personal eccentricities, Denk writes, “by grafting them onto Bach,” with the effect that his recordings “erase the distance of centuries; they dissolve the varnish that has piled up, and make Bach one with the anxieties of the present.” See Gould recording his 1981 “Goldberg” Variations further up, and read about the 2015 transcription of the recording by Nicholas Hopkins here.

Related Content:

Watch a 27-Year-Old Glenn Gould Play Bach & Put His Musical Genius on Display (1959)

Listen to Glenn Gould’s Shockingly Experimental Radio Documentary, The Idea of North (1967)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness