I’ve had Trout Mask Replica in my collection for years. I can’t say I regularly pull it out to give it a listen, but I know I’d never get rid of it. It’s a sometimes impenetrable slab of genius, wrought from endless sessions and then a short burst of recording, led by a man who couldn’t read music, was prone to fits of violent anger, but dammit knew what he wanted. (And Zappa produced.) When I learned later that the house where a lot of this went down was located in the hills behind the suburbs of Woodland Hills, it made the insurrection of the album all the more magical.

But yes, it’s a hard one to get into. There are no “hits.” There’s no foot tappin’ pop (well, mayyyyybe “Ella Guru,” and only because I knew it first as a cover by XTC.) It’s discordant. Don Van Vliet aka Captain Beefheart sounds possessed by Howlin’ Wolf trying to sing nursery rhymes on acid, and it often plays like members of the band are in different areas of the house with a vague idea of what the others are doing. (This is actually a bit close to the truth).

Vox’s continuing series “Earworm,” hosted by Estelle Caswell, attempts to convert listeners who may have never heard of the album, by taking apart the opening track, “Frownland.”

As Caswell explains, with help from musicologists Samuel Andreyev and Susan Rogers, Van Vliet melded blues and free jazz, and played it with a deconstructed rock band instrumentation. Drums and bass did not lock down a rhythm–they played independent of the others, with the bass even playing chords. Rhythm and lead guitar played two different time signatures each, and neither were easy, 4/4 rhythms. And then there’s the saxophone work, dropping in to squonk and thrash like Ornette Coleman. As Magic Band members point out, Van Vliet didn’t understand that a bass or a guitar did not have the same range of notes as an 88-key piano, which was Van Vliet’s songwriting instrument.

However, only jazzbos dig on learning about polyrhythms. There’s so many other reasons to appreciate Trout Mask. For one, it’s in the proud tradition of European surrealism but also comes from a particular “old weird America” that produced some of our most brilliant nutcases. (How many people, learning that Van Vliet was raised near Joshua Tree, nodded in enlightenment? Of course he was.) You want drug music, the album says…well then, this is the uncut stuff.

And then sometimes it really just hits hard: “Moonlight On Vermont” is relentless, with a corruscating guitar line and Beefheart worked up into a lather over “that old time religion.” He quotes Blind Willie Johnson, conflates paganism and Puritanism, and transcends both. (Maybe this is the gateway song for newbies?)

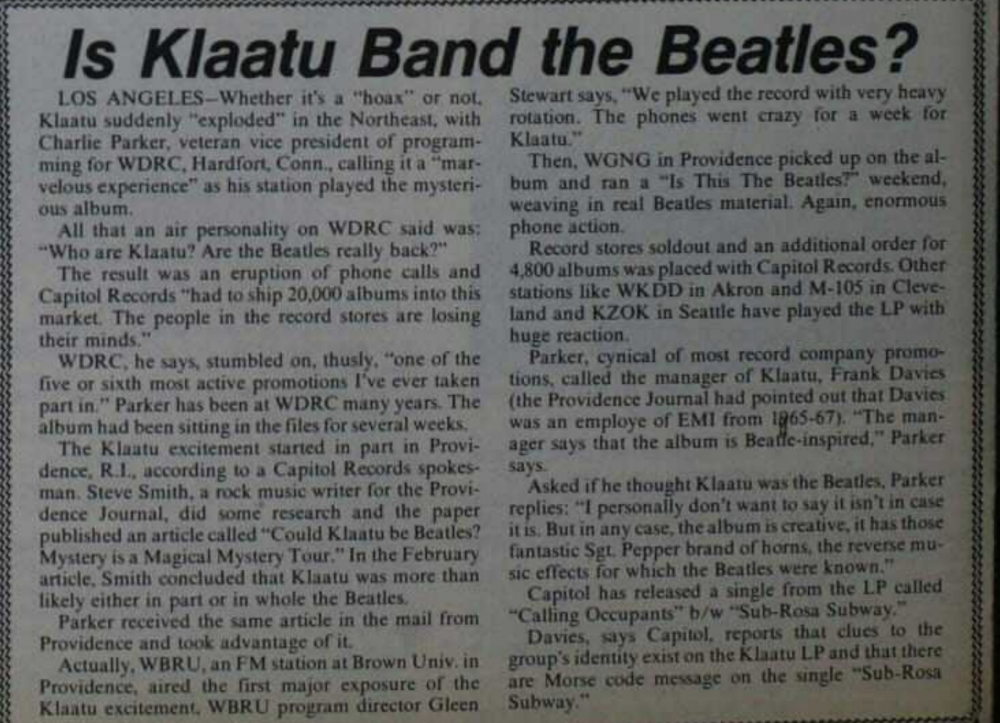

The Vox video precedes its defense with some negative reviews from the contemporary press, but this Dick Larson review from the time understood it from the get go, who writes about it as a giant step forward after Beefheart’s two previous, more accessible albums:

Dylan would sympathise with Beefheart’s ‘nature-and-love-trips’, but the Captain is faster and more bulbous (and he’s got his band). But this is it. In straightening out his music, he’s found some kind of religion. It may be in hair pies (yes!) or in Frownland, but mainly it’s people, children and country men and women. And this is a new delight for Beefheart – a rough outdoor humanity blended with humour and a rich verbal vomit of imagery.

It is a wild album, literally. There are field recordings in between the music, with sounds of crickets and a plane passing overhead. The LP art shows the band standing, crouching, and hiding in the overgrown backyard of the house. There’s mysterious things in the stream below and only some of them are fish.

Related Content:

Tom Waits Makes a List of His Top 20 Favorite Albums of All Time

Hear a Rare Poetry Reading by Captain Beefheart (1993)

Captain Beefheart Issues His “Ten Commandments of Guitar Playing”

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the artist interview-based FunkZone Podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.