A photograph of two old friends—Joni Mitchell and David Hockney—holding hands at Hockney’s L.A. solo exhibition took over the internet for a moment, for sentimental reasons Guy Trebay laid out in The New York Times. These include the fact that “Ms. Mitchell has seldom been seen in public since she says she was given a diagnosis of Morgellons disease, and suffered a brain aneurysm in 2015,” and “despite the presence of the cane she uses since having learned again to walk, Ms. Mitchell appears radiant and robust.”

Trebay does not include another reason that comes to mind: the two elderly artists, in their sweaters and adorable matching snap-brim hats, look like regular old folks on the way to a weekly chess match in the park. It’s a humanizing portrait of two giants of the art and music world, two people who, despite their wealth and fame, seem imminently down-to-earth and approachable; a warm and cheerful image, says Irish poet Sean Hewitt, who first shared it on Twitter, of “two successful people enjoying their old age.”

Doesn’t everyone especially want that for Joni Mitchell? Of all the beloved septuagenarian stars on the public’s radar these days, Mitchell garners more well-wishes than anyone—rallying generations of stars and musicians for a 75th birthday tribute concert last November. The show appeared in theaters (see a trailer below) and has been released as a superb album of live covers called Joni 75. So much of the love for Mitchell—her undisputed brilliance as a songwriter, guitarist, and performer notwithstanding—has to do with the amount of personal pain she overcame to make it as an artist.

Born Roberta Joan Anderson in Alberta, Canada, her early struggles gave her musical voice so much poignancy and authenticity. As she herself has said, “I wouldn’t have pursued music but for trouble.” A bout with polio at age nine, a push against her parents’ expectations to claim her identity as a visual artist and musician… then, at age 20, Mitchell’s boyfriend left her, “three months pregnant in an attic room with no money and winter coming on,” she later wrote. She gave up the baby for adoption, and the decision haunted her for years. In 1982’s “Chinese Café,” she sang “Your kids are coming up straight / My child’s a stranger / I bore her / But I could not raise her.”

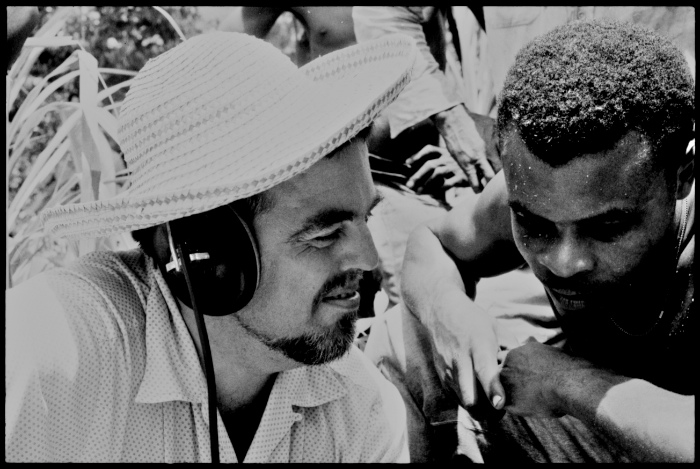

The following year, 1966, she married American folk singer Chuck Mitchell, took the name we know her by, and left Canada for the first time to make musical history. But first, she appeared on a Canadian television program called Let’s Sing Out, hosted by folk singer Oscar Brand and recorded on college campuses across the country between 1963 and 1967. The first ’65 episode at the top captures Mitchell—then Joan Anderson—singing her unreleased “Born to Take the Highway” at the University of Manitoba, a prescient song that “imagined cars and women differently” than the typical road songs of “powerful muscle cars” and “jacked-up masculinity and sexual conquest,” writes the blog Women in Rock.

“I was born to take the highway / I was born to chase a dream,” she sings, certainties that reverberate through her music and her life. Brand introduces Mitchell as an example of the movement in folk music toward the “self-written song.” She appears with him later on that same broadcast to sing “Blow Away the Morning Dew” (a young Dave Van Ronk also appeared on the show). In subsequent broadcasts in the compilation, we see “Joan Anderson” more confidently inhabit the persona that would propel her to fame first in Canada, then the States, then the world. She performs solo and with the Chapins, then, finally as Joni Mitchell, in two 1966 broadcasts. Find a tracklist of each classic performance below, and, if you haven’t already, take some time out to celebrate Mitchell’s 75th by revisiting the beginnings of her career over fifty years ago.

October 4, 1965 — With The Chapins and Dave Van Ronk

00:00 — Opening

01:22 — Born to Take the Highway

04:25 — Blow Away the Morning Dew

October 4, 1965 — With The Chapins and Patrick Sky

07:52 — Opening

09:05 — Favorite Color

12:00 — Me and My Uncle

October 24, 1966 — With Bob Jason and Jimmy Driftwood

15:08 — Opening

17:20 — Just Like Me

20:15 — Urge for Going

October 24, 1966 — With Bob Jason and the Allen-Ward Trio

24:08 — Opening

25:05 — Night in the City

27:55 — Blue on Blue

30:30 — Let’s Get Together (Allen-Ward Trio)

33:37 — Prithee, Pretty Maiden

Related Content:

For Joni Mitchell’s 70th Birthday, Watch Classic Performances of “Both Sides Now” & “The Circle Game” (1968)

Stream Joni Mitchell’s Complete Discography: A 17-Hour Playlist Moving from Song to a Seagull (1968) to Shine (2007)

Joni Mitchell Sings an Achingly Pretty Version of “Both Sides Now” on the Mama Cass TV Show (1969)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness