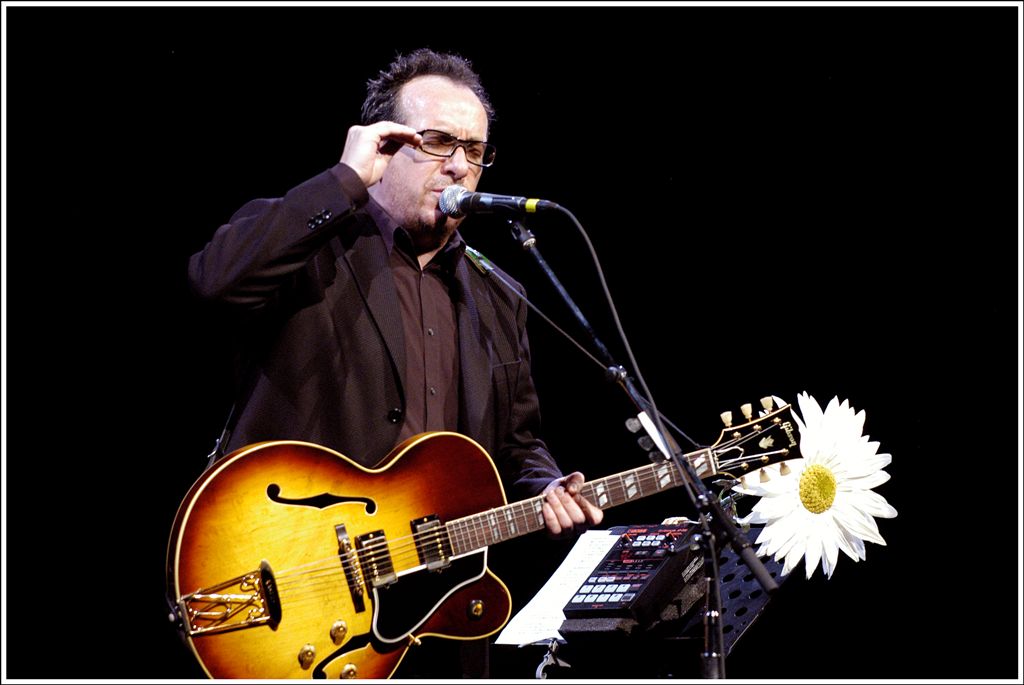

Photo by Victor Diaz Lamich, via Wikimedia Commons

Ask a few friends to draw up sufficiently long lists of their favorite albums, and chances are that more than one of them will include Elvis Costello. But today we have for you a list of 500 essential albums that includes no Elvis Costello records at all — not least because it was put together by Elvis Costello. “Here are 500 albums that can only improve your life,” he writes in his introduction to the list, originally published in Vanity Fair. “Many will be quite familiar, others less so.” Costello found it impossible “to choose just one title by Miles Davis, the Beatles, Joni Mitchell, Dylan, Mingus, etc.,” but he also made room for less well-known musical names such as David Ackles, perhaps the greatest unheralded American songwriter of the late 60s.”

Costello adds that “you may have to go out of your way” to locate some of the albums he has chosen, but he made this list in 2000, long before the internet brought even the most obscure selections within a few keystrokes’ reach with streaming services like Spotify–on which a fan has even made the playlist of Costello’s 500 albums below.

And when Costello writes about having mostly excluded “the hit records of today,” he means hit records by the likes of “Marilyn, Puffy, Korn, Eddie Money — sorry, Kid Rock — Limp Bizkit, Ricky, Britney, Backstreet Boys, etc.” But when he declares “500 albums you need,” described only with a highlighted track or two (“When in doubt, play Track 4—it is usually the one you want”), all remain enriching listens today. The list begins as follows:

- ABBA: Abba Gold (1992), “Knowing Me, Knowing You.”

- DAVID ACKLES: The Road to Cairo (1968), “Down River” Subway to the Country (1969), “That’s No Reason to Cry.”

- CANNONBALL ADDERLEY: The Best of Cannonball Adderley (1968), “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy.”

- AMY ALLISON: The Maudlin Years (1996), “The Whiskey Makes You Sweeter.”

- MOSE ALLISON: The Best of Mose Allison (1970), “Your Mind Is on Vacation.”

- ALMAMEGRETTA: Lingo (1998), “Gramigna.”

- LOUIS ARMSTRONG: The Complete Hot Five and Hot Seven Recordings (2000), “Wild Man Blues,” “Tight Like This.”

- FRED ASTAIRE: The Astaire Story (1952), “They Can’t Take That Away from Me.”

How many music collections, let alone lists of essential records, would put all those names together? And a few hundred albums later, the bottom of Costello’s alphabetically organized list proves equally diverse and culturally credible:

- RICHARD WAGNER: Tristan and Isolde (conductor: Wilhelm Furtwangler; 1952); Der Ring des Nibelungen (conductor: George Solti; 1983).

- PORTER WAGONER AND DOLLY PARTON: The Right Combination: Burning the Midnight Oil (1972), “Her and the Car and the Mobile Home.”

- TOM WAITS: Swordfishtrombones (1983), “16 Shells from a Thirty-Ought-Six,” “In the Neighborhood” Rain Dogs (1985), “Jockey Full of Bourbon,” “Time” Frank’s Wild Years (1987), “Innocent When You Dream,” “Hang on St. Christopher” Bone Machine (1992), “A Little Rain,” “I Don’t Wanna Grow Up” Mule Variations (1999), “Take It with Me,” “Georgia Rae,” “Filipino Box-Spring Hog.”

- SCOTT WALKER: Tilt (1995), “Farmer in the City.”

- DIONNE WARWICK: The Windows of the World (1968), “Walk Little Dolly.”

- MUDDY WATERS: More Real Folk Blues (1967), “Too Young to Know.”

- DOC WATSON: The Essential Doc Watson (1973), “Tom Dooley.”

- ANTON WEBERN: Complete Works (conductor: Pierre Boulez; 2000).

- KURT WEILL: O Moon of Alabama (1994), Lotte Lenya, “Wie lange noch?”

- KENNY WHEELER with LEE KONITZ, BILL FRISELL and DAVE HOLLAND: Angel Song (1997).

- THE WHO: My Generation (1965), “The Kids Are Alright” Meaty, Beaty, Big and Bouncy (1971), “Substitute.”

- HANK WILLIAMS: 40 Greatest Hits (1978), “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” “I’ll Never Get out of This World Alive.”

- LUCINDA WILLIAMS: Car Wheels on a Gravel Road (1998), “Drunken Angel.”

- SONNY BOY WILLIAMSON: The Best of Sonny Boy Williamson (1986), “Your Funeral and My Trial,” “Help Me.”

- JESSE WINCHESTER: Jesse Winchester (1970), “Quiet About It,” “Black Dog,” “Payday.”

- WINGS: Band on the Run (1973), “Let Me Roll It.”

- HUGO WOLF: Lieder (soloist: Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau; 2000), “Alles Endet, Was Entstehet.”

- BOBBY WOMACK: The Best of Bobby Womack (1992), “Harry Hippie.”

- STEVIE WONDER: Talking Book (1972), “I Believe (When I Fall in Love It Will Be Forever)” Innervisions (1973), “Living for the City” Fulfillingness’ First Finale (1974), “You Haven’t Done Nothin’.”

- BETTY WRIGHT: The Best of Betty Wright (1992), “Clean Up Woman,” “The Baby Sitter,” “The Secretary.”

- ROBERT WYATT: Mid-Eighties (1993), “Te Recuerdo Amanda.”

- LESTER YOUNG: Ultimate Lester Young (1998), “The Man I Love.”

- NEIL YOUNG: Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere (1969), “Down by the River” After the Goldrush (1970), “Birds” Time Fades Away (1973), “Don’t Be Denied” On the Beach (1974), “Ambulance Blues” Freedom (1989), “The Ways of Love” Ragged Glory (1990), “Fuckin’ Up.”

- ZAMBALLARANA: Zamballarana (1997), “Ventu.”

Zamballarana, for the many who won’t recognize the name, is a band from the Corsican village of Pigna whose music, according to one description, combines “archaic male polyphony with elements of jazz, oriental and latin music as well as the innovative way of playing traditional Corsican instruments such as the 16-string Cetrea, the drum Colombu and the flute Pivana.” That counts as just one of the unexpected listening experiences awaiting those who fire up their favorite music-streaming service and work their way through Costello’s list of 500 essential albums. It may also inspire them to determine their own essential albums, an activity Costello endorses as musically salutary: “Making this list made me listen all over again.”

via Far Out Magazine

Related Content:

Hear the 10 Best Albums of the 1960s as Selected by Hunter S. Thompson

Lou Reed Creates a List of the 10 Best Records of All Time

Tom Waits Makes a List of His Top 20 Favorite Albums of All Time

Elvis Costello Sings “Penny Lane” for Sir Paul McCartney

The Stunt That Got Elvis Costello Banned From Saturday Night Live (1977)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.