I wish I had more sense of humor

Keeping the sadness at bay

Throwing the lightness on these things

Laughing it all away

— Joni Mitchell, “People’s Parties”

Joni Mitchell has been showered with tributes of late, many of them connected to her all-star 75th birthday concert last November.

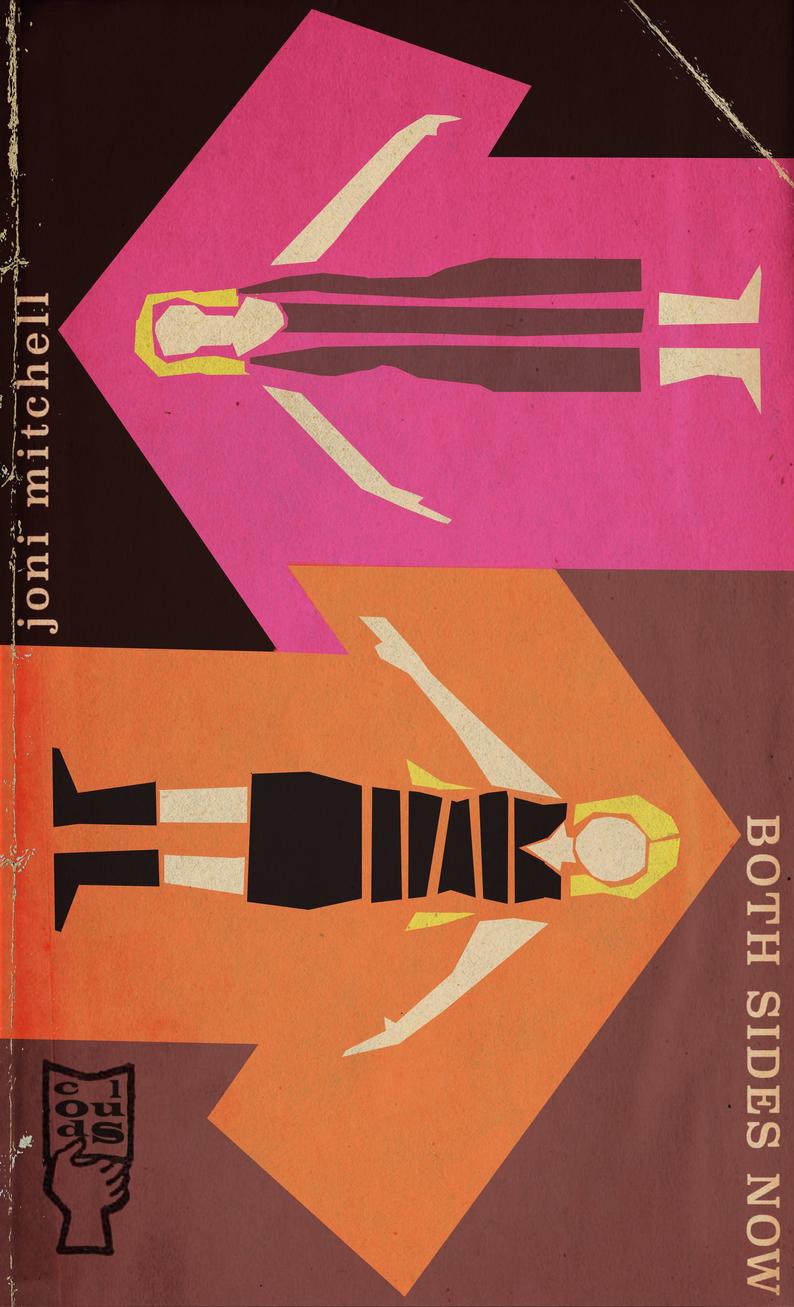

The silky voiced Seal, who credits Mitchell with inspiring him to become a musician, soaring toward heaven on “Both Sides Now”…

“A Case Of You” as a duet for fellow Newport Folk Festival alums Kris Kristofferson and Brandi Carlile….

Chaka Khan injecting a bit of funk into “Help Me,” a tune she’s been covering for 20 some years…

They’re moving and beautiful and sensitive, but given that Mitchell’s the one behind the immortal lyric “laughing and crying, you know it’s the same release…,” shouldn’t someone aim for the funny bone? Mix things up a little?

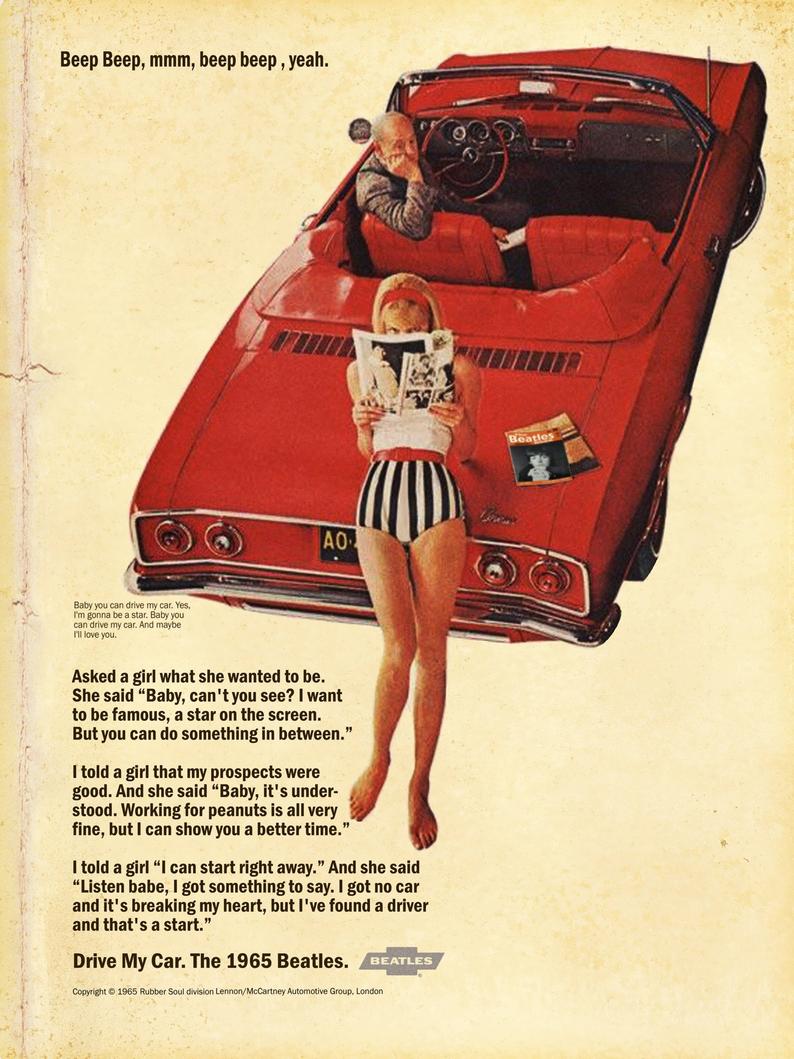

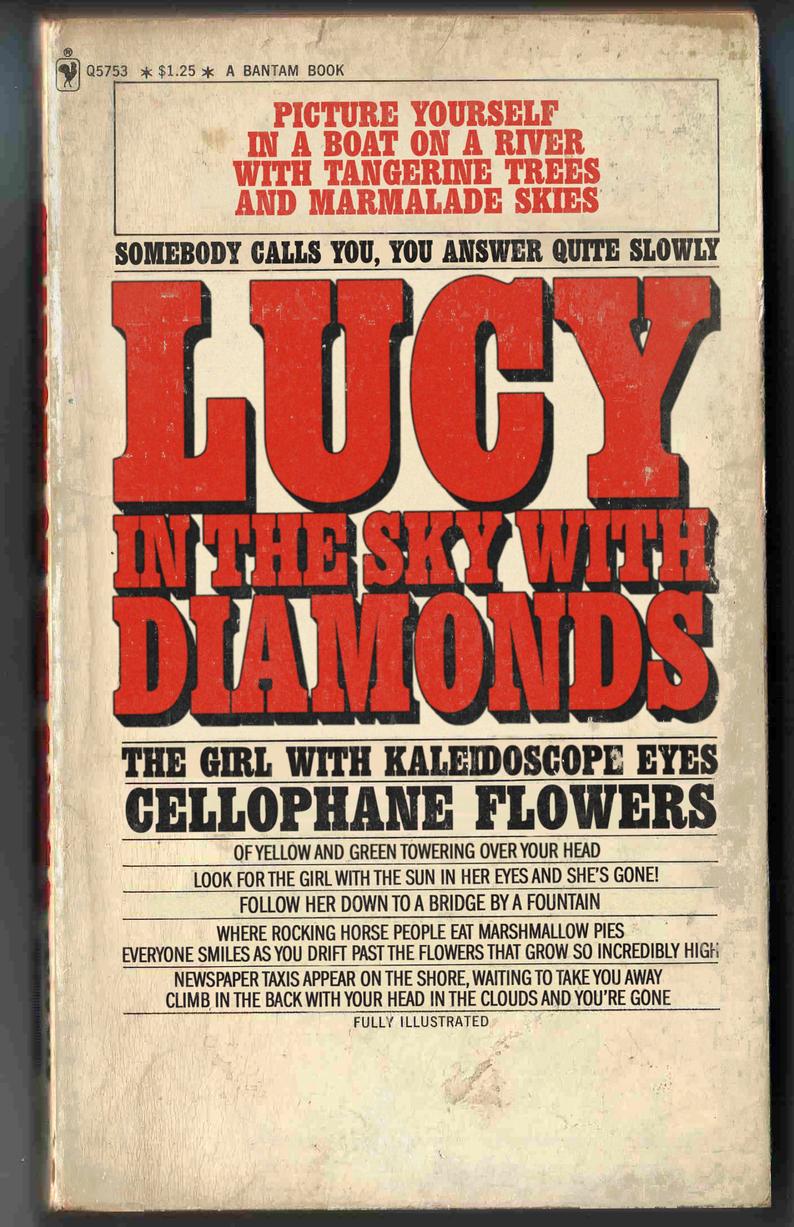

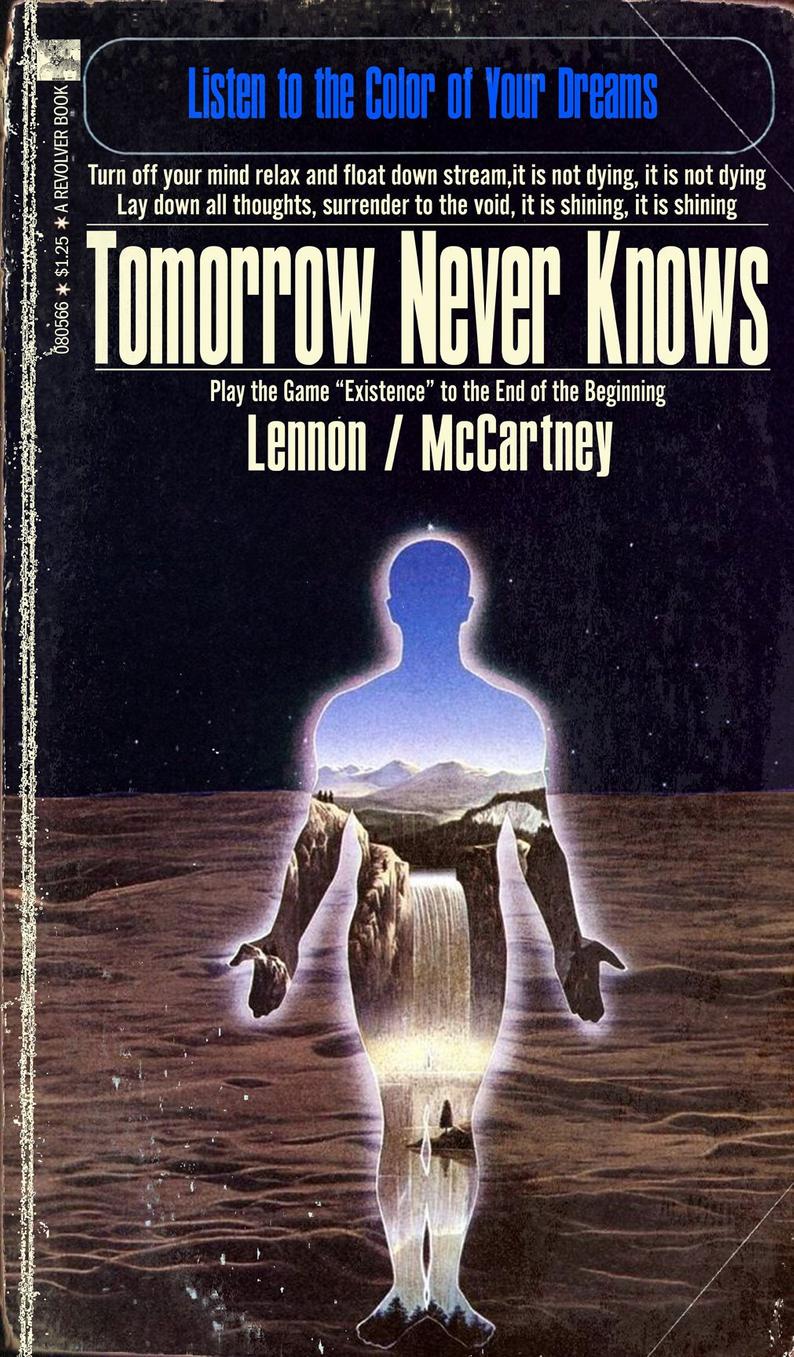

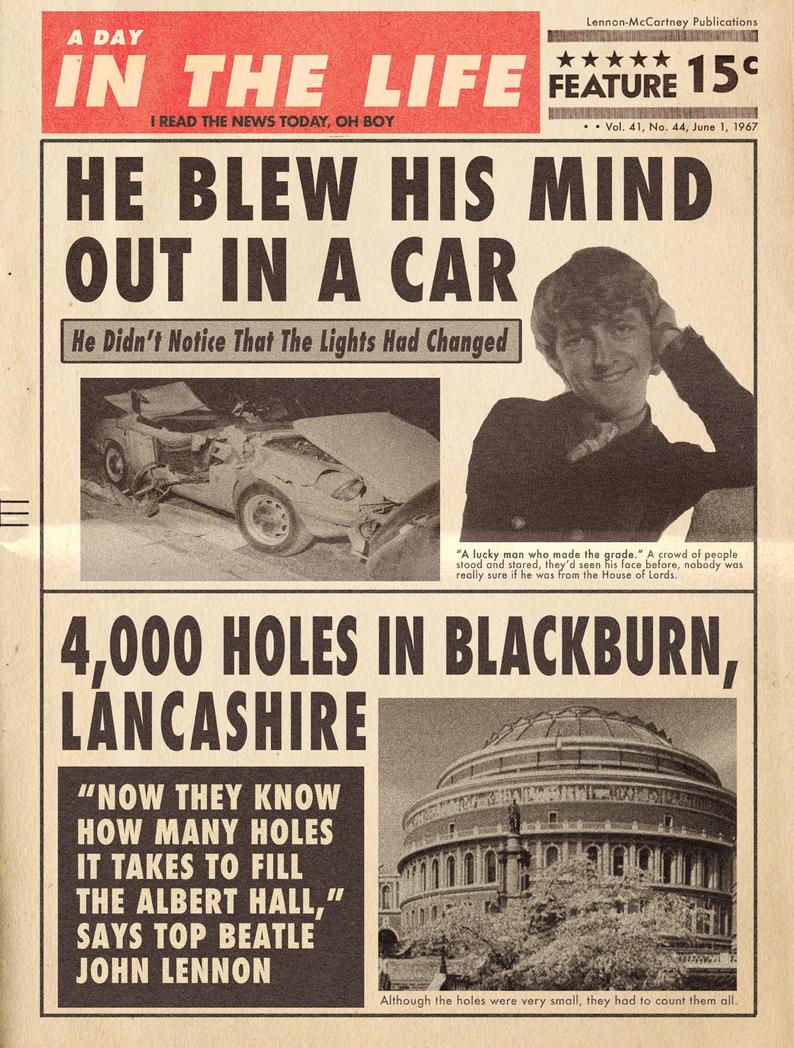

Enter Todd Alcott, who’s been delighting us all year with his “mid-century mashups,” an irresistible combination of vintage paperback covers, celebrity personae, and iconic lyrics from the annals of rock and pop.

His homage to “Help Me,” above, is decidedly on brand. The lurid 1950s EC horror comic-style graphics confer a dishy naughtiness that was—no disrespect—rather lacking in the original.

Perhaps Mitchell would approve of these monkeyshines?

A 1991 interview with Rolling Stone’s David Wild suggests that she would have at some point in her life:

When I was a kid, I was a real good-time Charlie. As a matter of fact, that was my nickname. So when I first started making all this sensitive music, my old friends back home could not believe it. They didn’t know – where did this depressed person come from? Along the way, I had gone through some pretty hard deals, and it did introvert me. But it just so happened that my most introverted period coincided with the peak of my success.

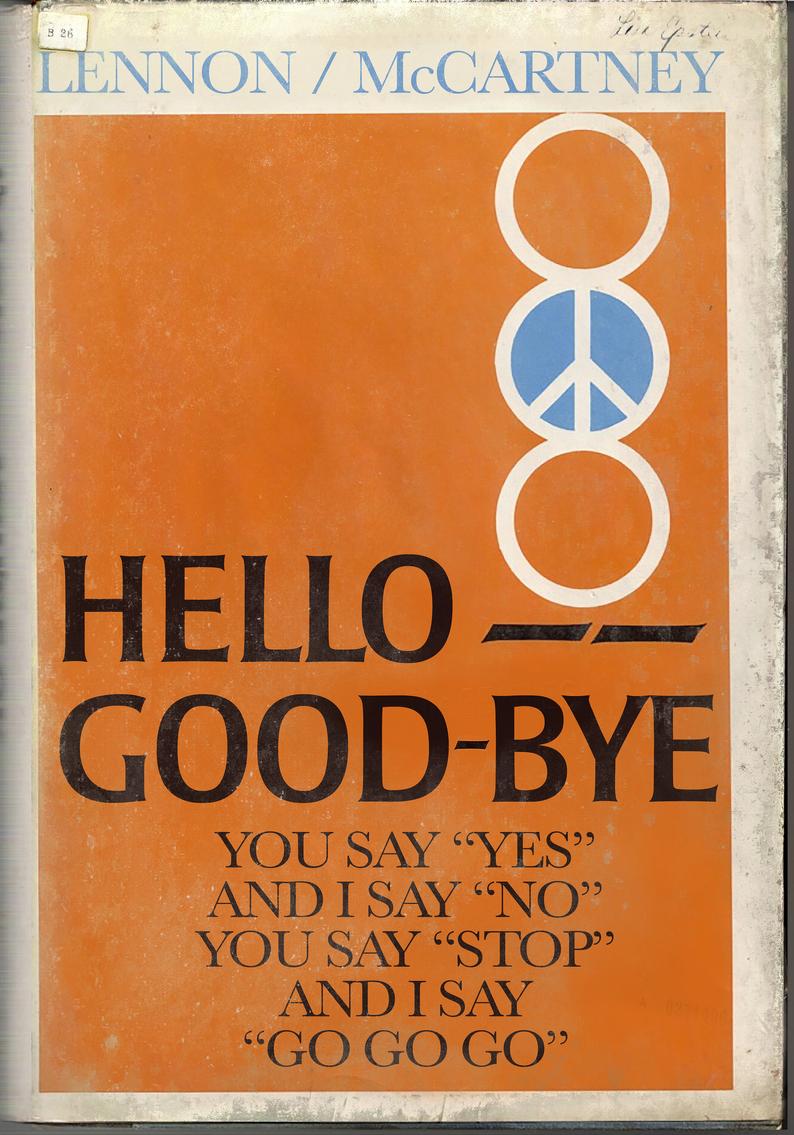

Alcott honors the introvert by rendering “Both Sides Now” as an angsty-looking volume of 60s-era poetry from the imaginary publishing house Clouds.

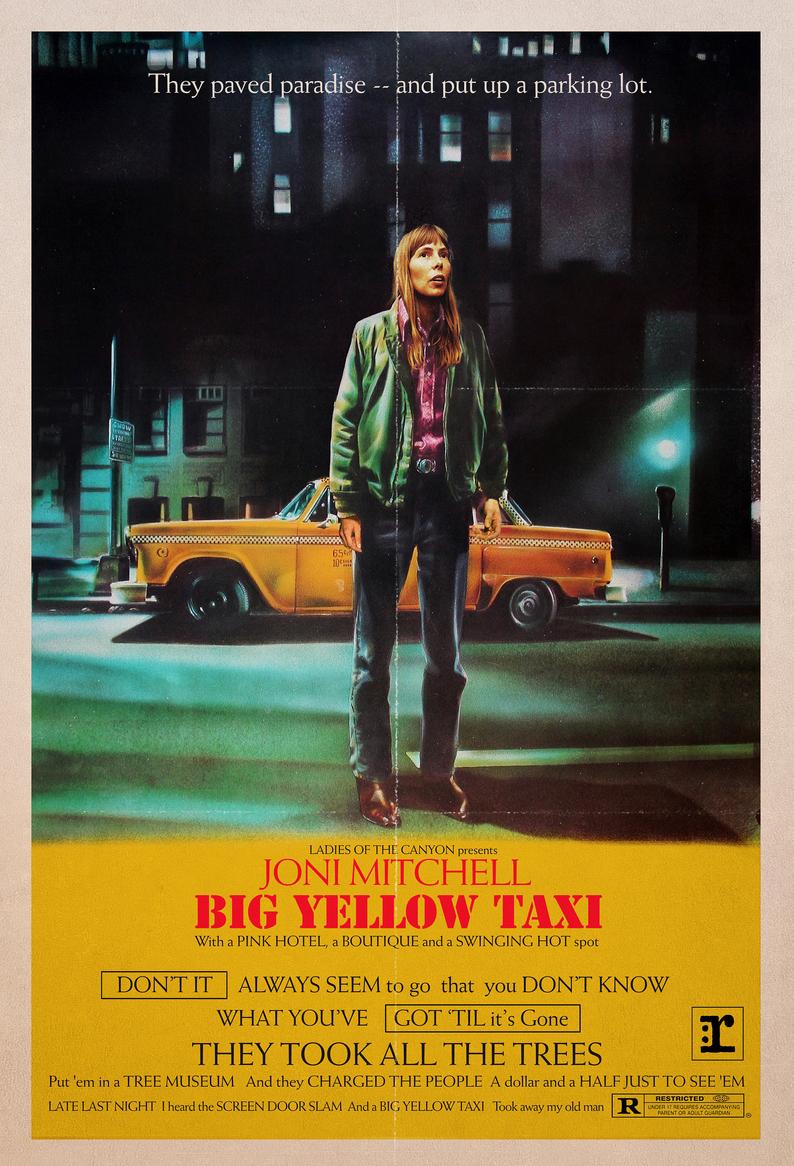

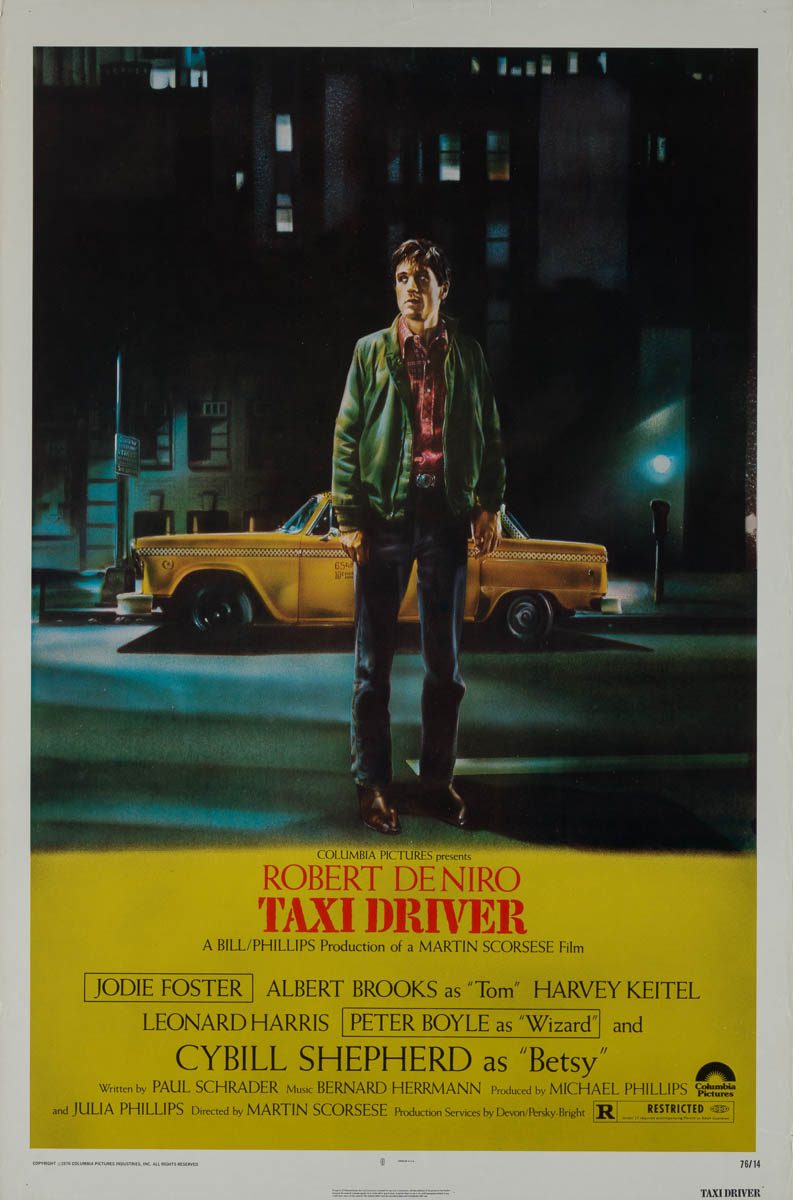

“Big Yellow Taxi” carries Alcott from the bookshelf to the realm of the movie poster.

The lyrics are definitely the star here, but it’s fun to note just how much mileage he gets out of the floating text boxes that were a strangely random-feeling feature of the original.

Also “Ladies of the Canyon” is a great producer’s credit. Given Alcott’s own screenwriting credits on IMDB, perhaps we could convince him to mash a bit of Joni’s sensibility into some of Paul Schrader’s grimmest Taxi Driver scenes…

That said, it’s worth remembering that Alcott’s creations are loving tributes to the artists who matter most to him. As he told Open Culture:

Joni Mitchell is one of the most criminally undervalued American songwriters of the 20th century, and that now that I live in LA, every time I drive through Laurel Canyon I think about her and that whole absurdly fertile scene in the late 1960s, when artists could afford to live in Laurel Canyon and Joni Mitchell was hanging out with Neil Young and Charles Manson.

See all of Todd Alcott’s work here. (Please note that this is his official sales site… beware of imposters selling quickie knock-offs of his designs on eBay and Facebook.) Find other posts featuring his work in the Relateds below.

Related Content:

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inkyzine. Join her in NYC on Monday, September 9 for a new season of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday.