FYI: If you sign up for a MasterClass course by clicking on the affiliate links in this post, Open Culture will receive a small fee that helps support our operation.

To have watched some of the greatest film and television in the last thirty-five years is to have been immersed in the music of Mark Mothersbaugh and Danny Elfman—two artists who have scored Hollywood blockbusters and indie hits alike since the mid-eighties when they started on TV’s Pee-wee’s Playhouse and Tim Burton’s 1985 comedy Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, respectively. They also happen to have played in two of the 1980’s weirdest, most experimental New Wave bands, Devo and Oingo Boingo.

Mothersbough went on to score everything from Rugrats to Thor: Ragnarok, but he’s maybe best known for his work with Wes Anderson. Likewise, Elfman—who has worked with everyone from Gus Van Sant to Brian De Palma to Peter Jackson to Ang Lee—formed a creative bond with Burton, to such a degree that it’s near impossible to imagine a Tim Burton film without a Danny Elfman score.

When Burton first approached him for Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, the Oingo Boingo frontman was just about to release “Weird Science,” for the infamous John Hughes film of the same name. Already a band with a massive cult following, they became pop stars, and Elfman became one of the most distinctive film composers of the last several decades.

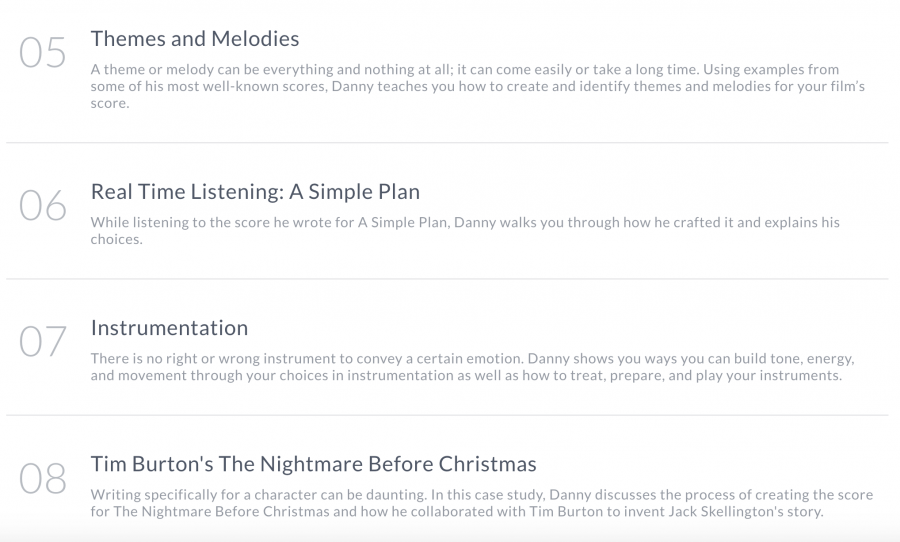

He scored Beetlejuice, Batman, Edward Scissorhands, Batman Returns, Sleepy Hollow, The Nightmare Before Christmas, Corpse Bride, and, most recently, Burton’s Dumbo. Now he’s sharing his secrets for aspiring film composers everywhere with his very own Masterclass. “I’m going to tell you from my perspective,” he says in the trailer above, “how I do these things”: things including instrumentation, orchestration, melody, and tone—“the most important thing you’re going to capture in a film score.”

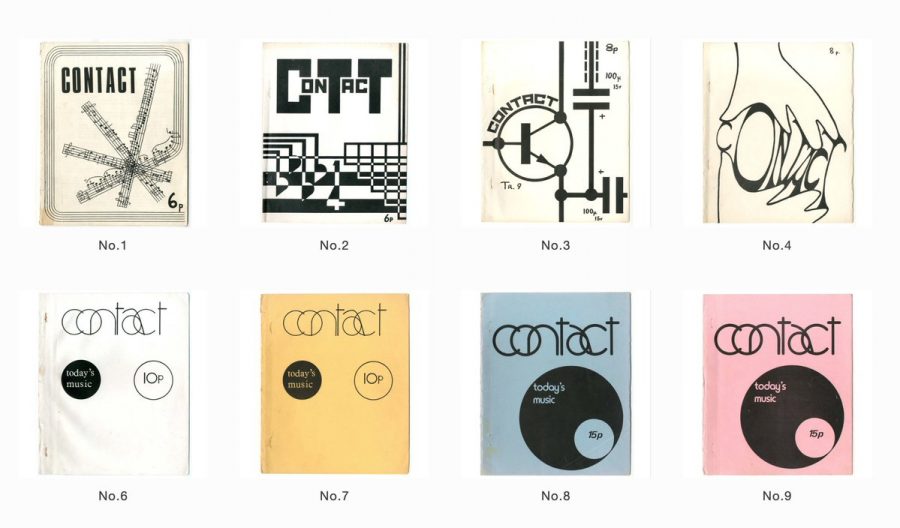

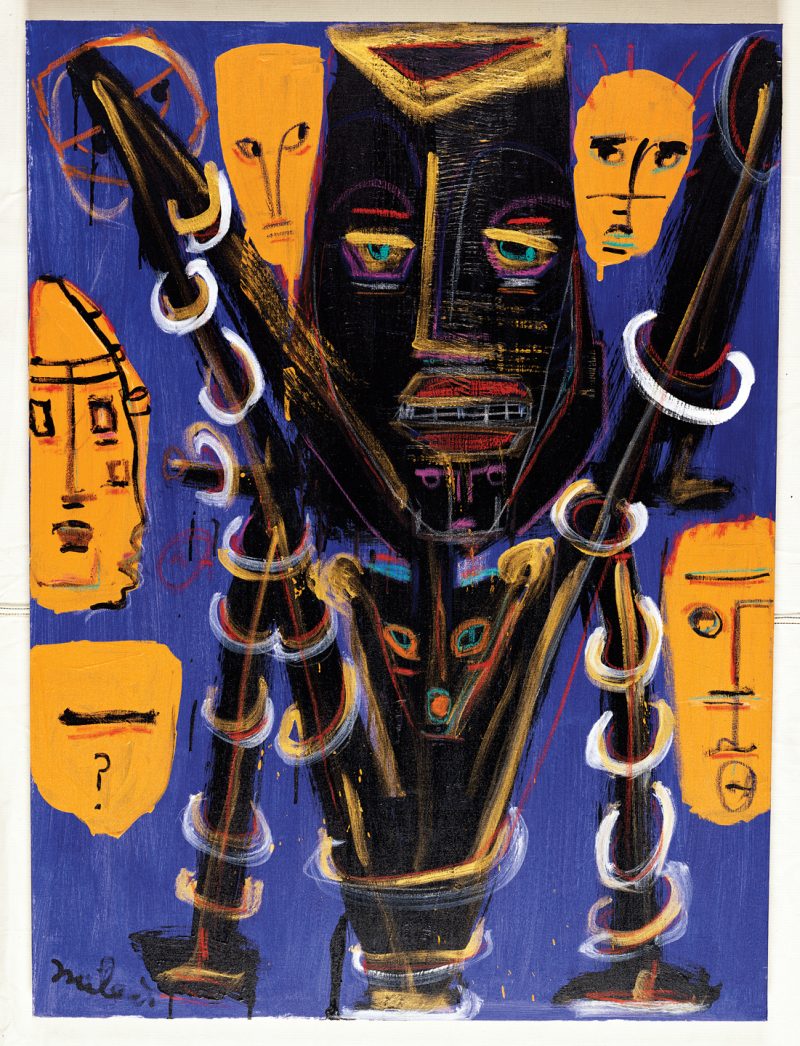

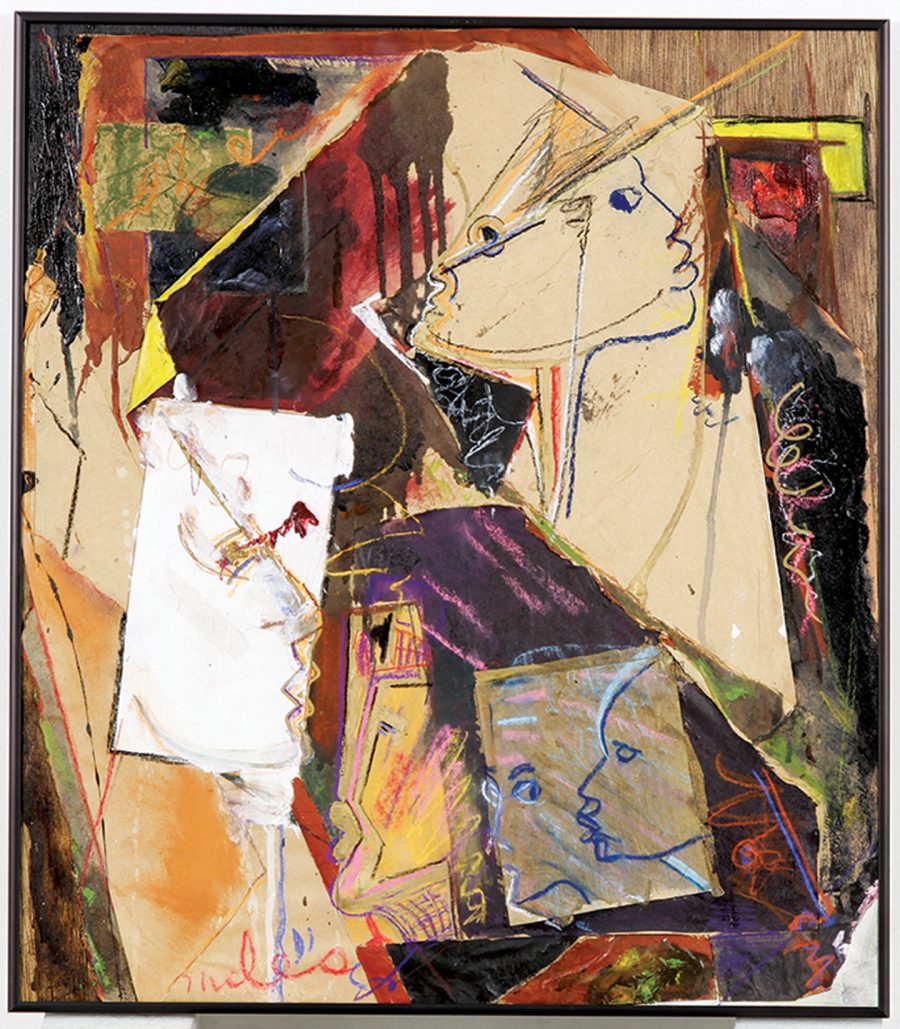

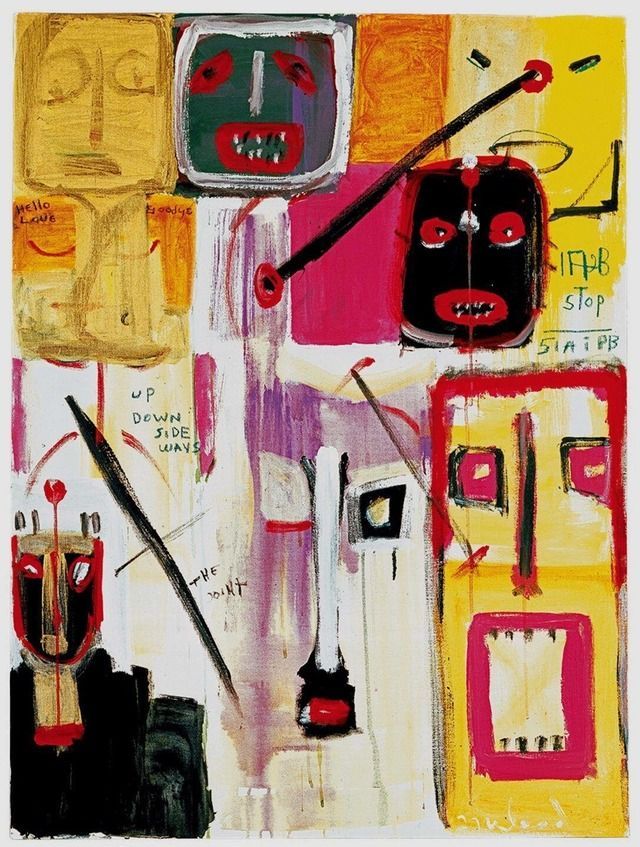

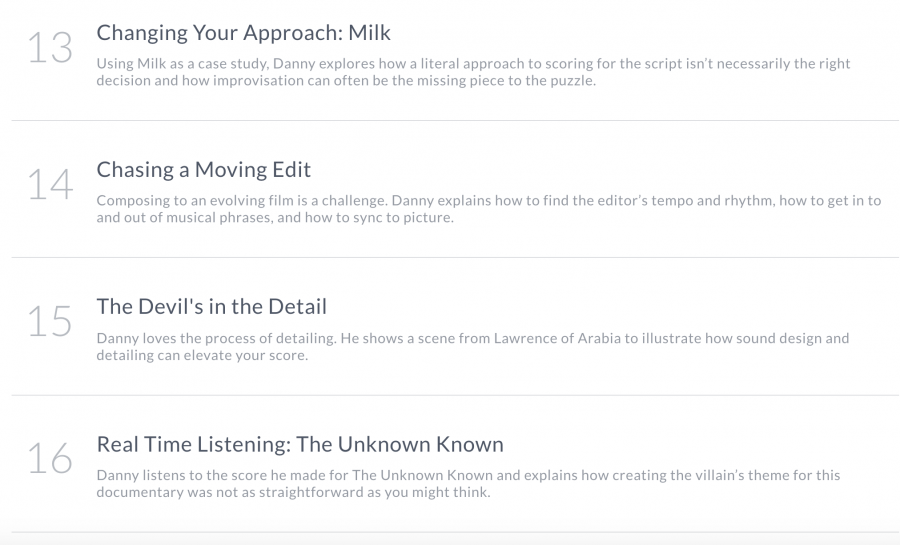

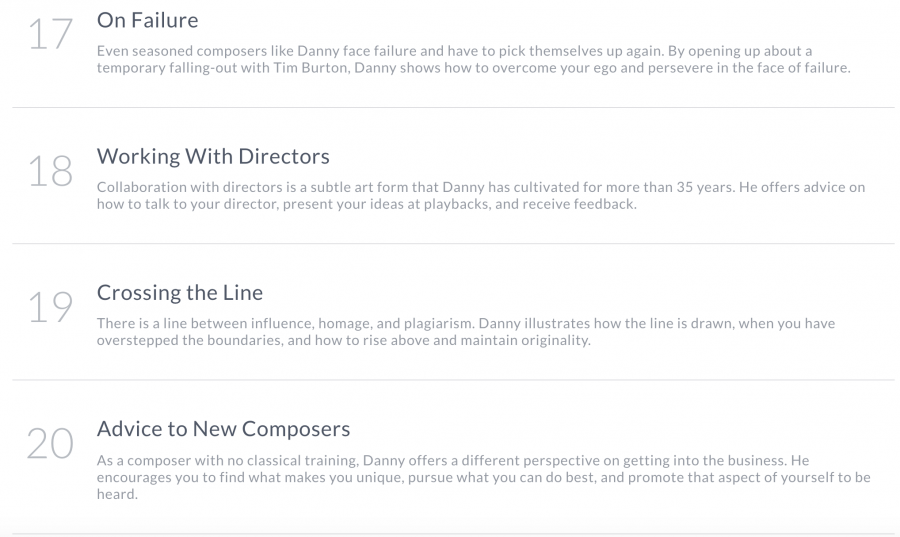

In the screenshots here, see excerpts of the course topics, which include units on the films Milk, The Unknown Known, and The Nightmare Before Christmas, an example of “writing specifically for a character”—a character, Jack Skellington, whose singing voice Elfman also provided.

For those who feel they’ll never measure up to a career like Danny Elfman’s, he introduces all important units on insecurity and failure. Perhaps the most important lesson of all, he says above, with infectious enthusiasm, is learning that “it’s okay to fail, to feel insecure. Doubting yourself, finding confidence and moving forward, and then doubting what you’ve just done…. I think this is the life of a composer. I think it’s the life of an artist.”

Can such things be taught, or can they only be lived? Each teacher and student of the arts must at some point ask themselves this question. Perhaps they only learn the answer when they try, and fail, and try again anyway. Sign up for Elman’s course here.

You can take this class by signing up for a MasterClass’ All Access Pass. The All Access Pass will give you instant access to this course and 85 others for a 12-month period.

Related Content:

How to Take Every MasterClass Course For Less Than a Cup of Good Coffee

All of the Music from Martin Scorsese’s Movies: Listen to a 326-Track, 20-Hour Playlist

Brian Eno Reveals His Favorite Film Soundtracks

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness