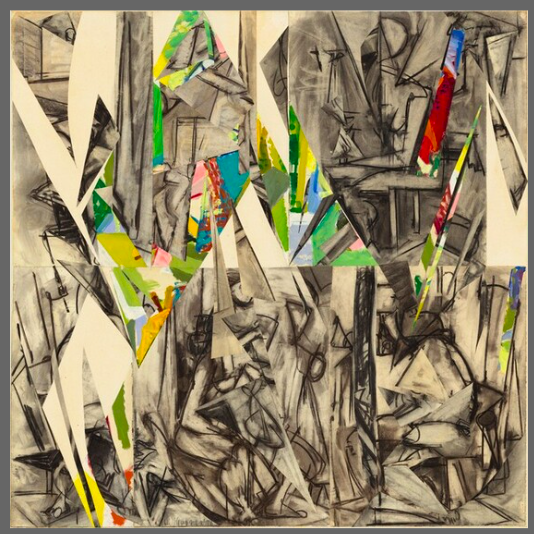

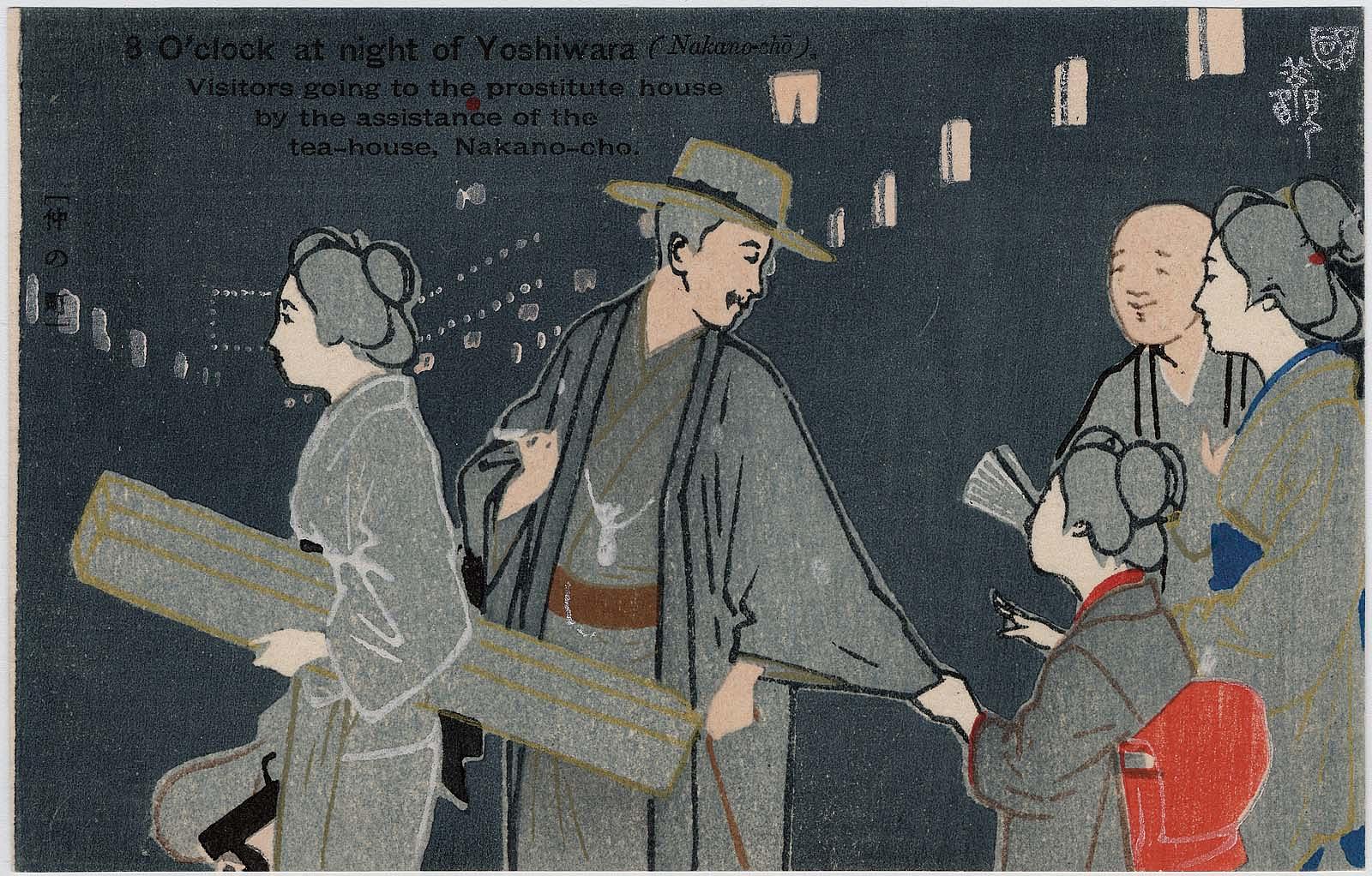

Though it may not figure prominently into the average whirlwind Eurail trip across the continent, Vienna’s role in the development of European culture as we know it can hardly be overstated. Granted, the names of none of its cultural institutions come mind as readily as those of the Prado, the Uffizi Gallery, or the Louvre. But as museums go, Vienna more than holds its own, both inside and outside the neighborhood aptly named the Museumsquartier — and not just in the physical world, but online as well. Recently, the Albertina Museum in Vienna put into the public domain 150,000 of its digitized works, all of which you can browse on its web site.

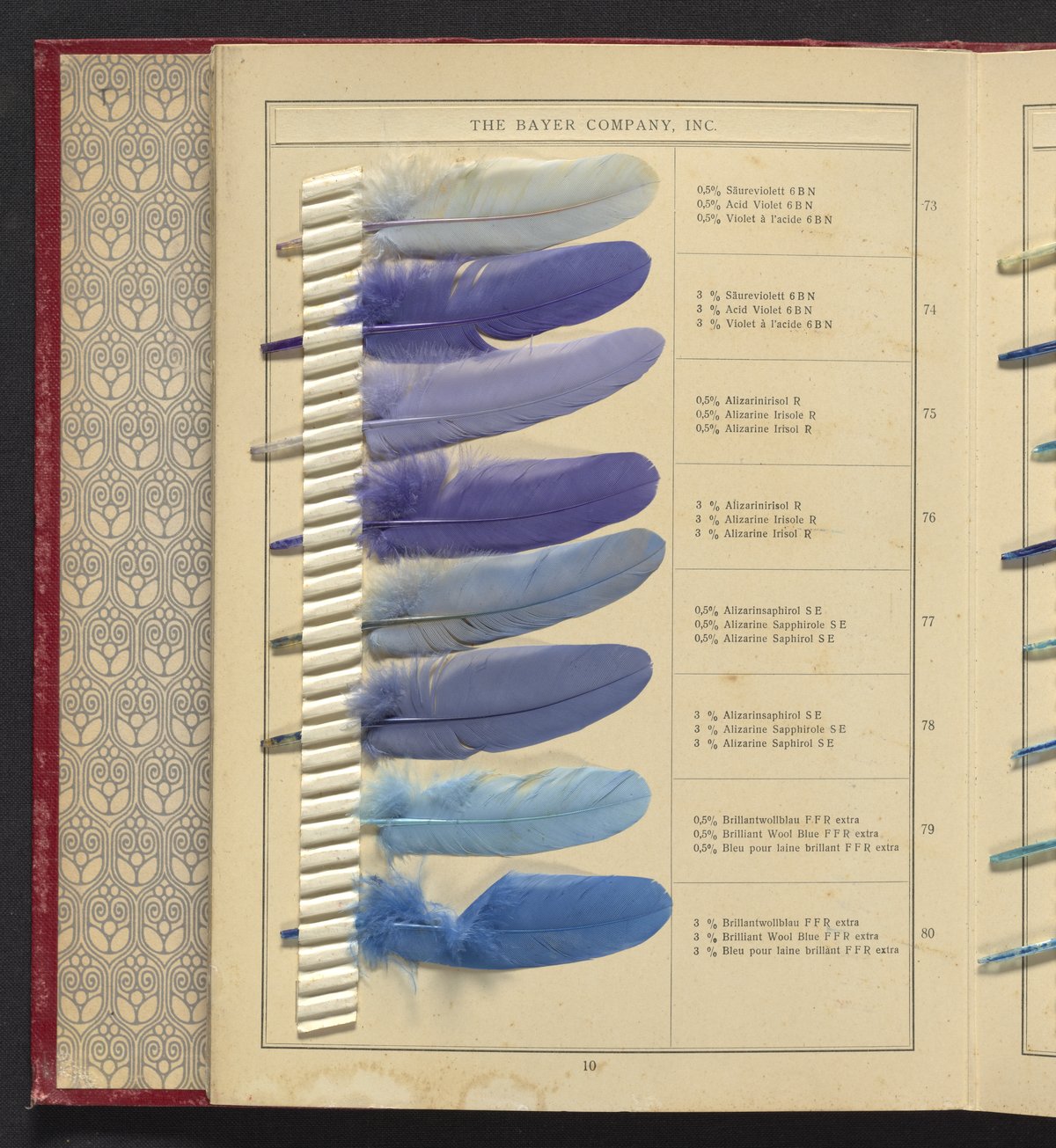

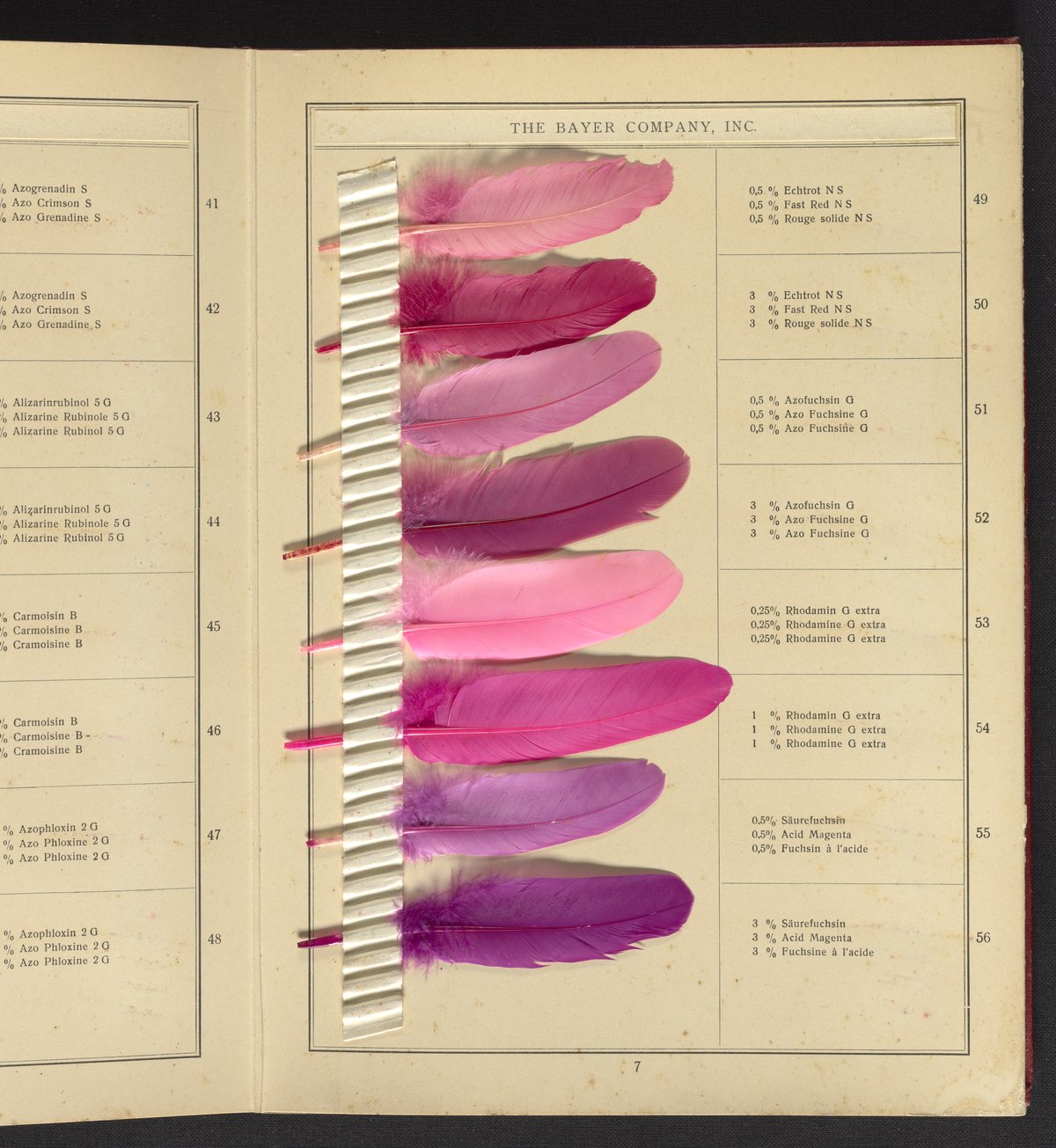

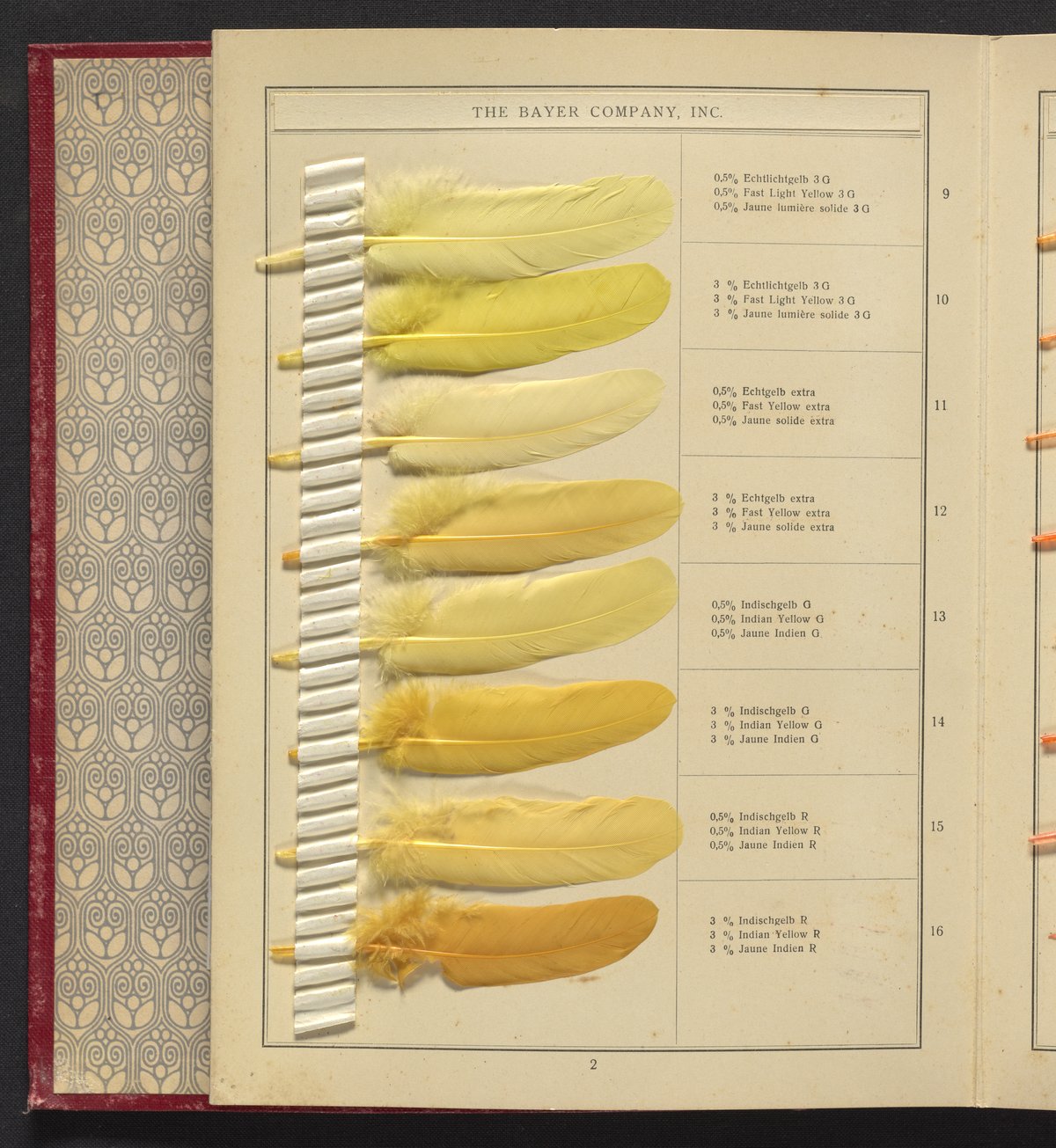

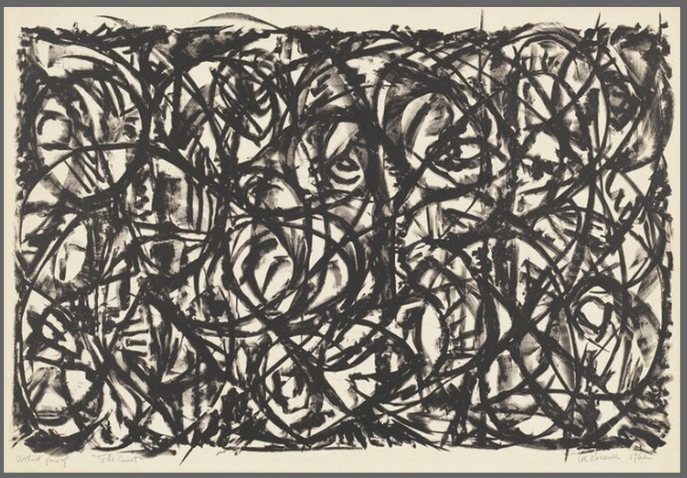

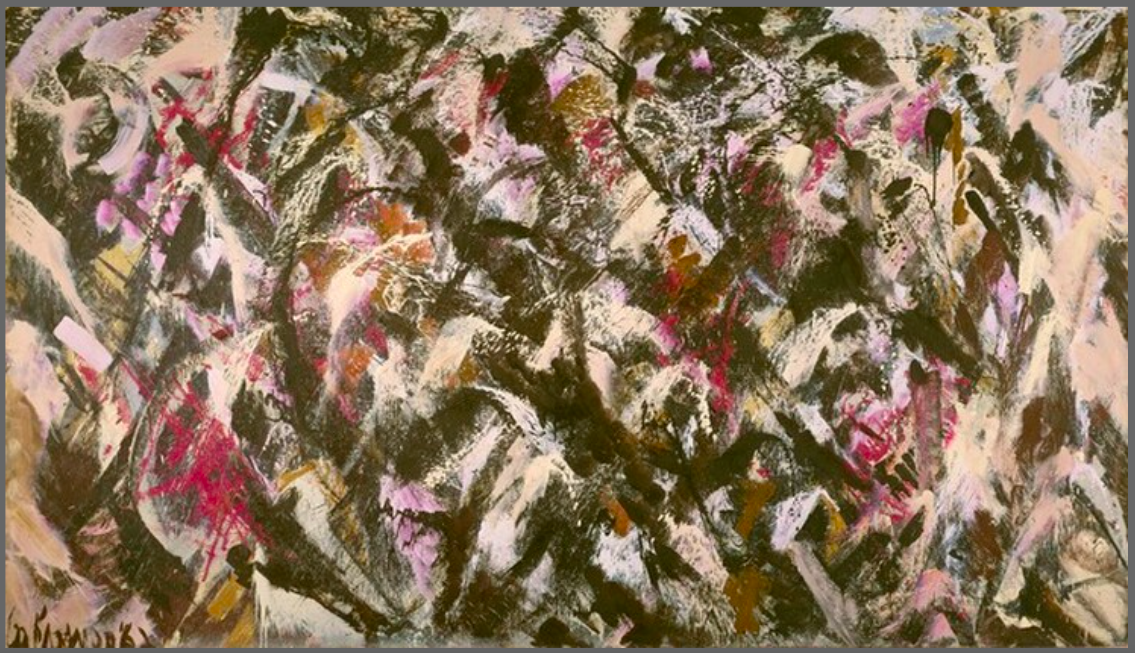

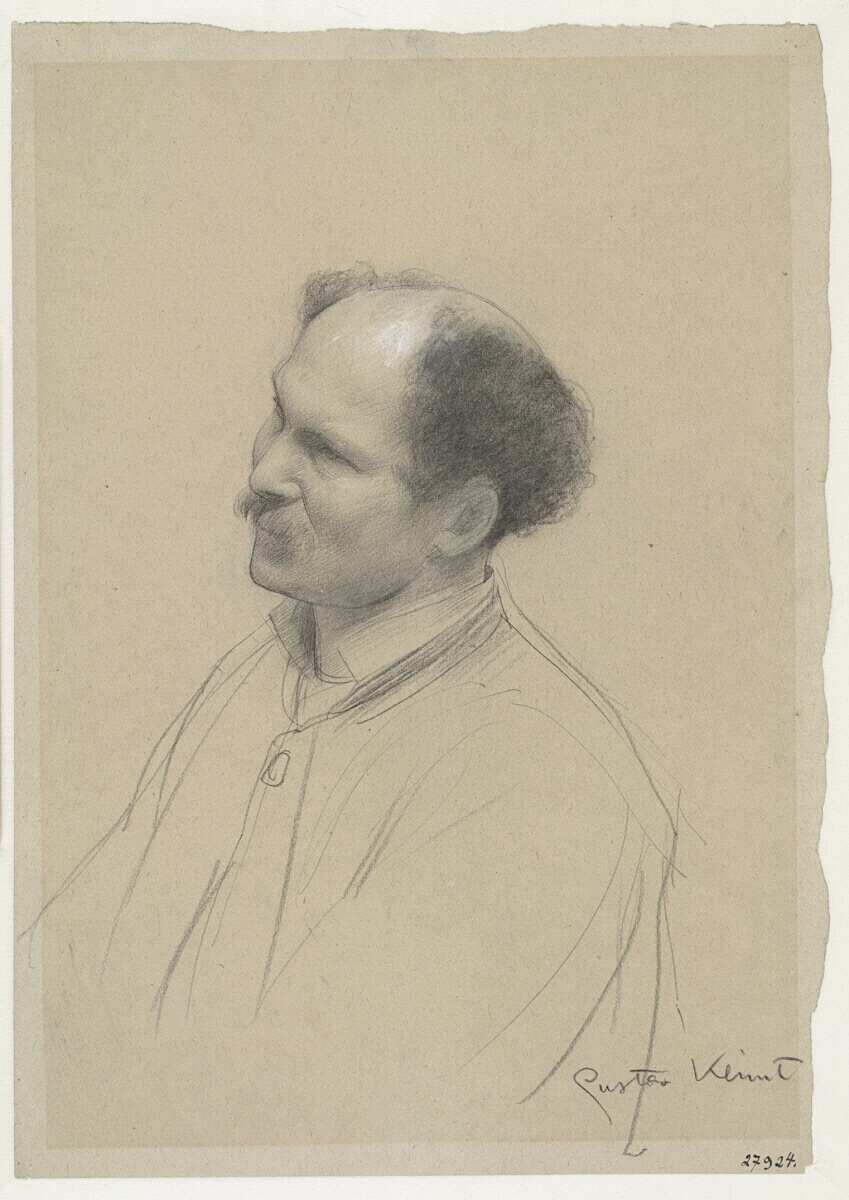

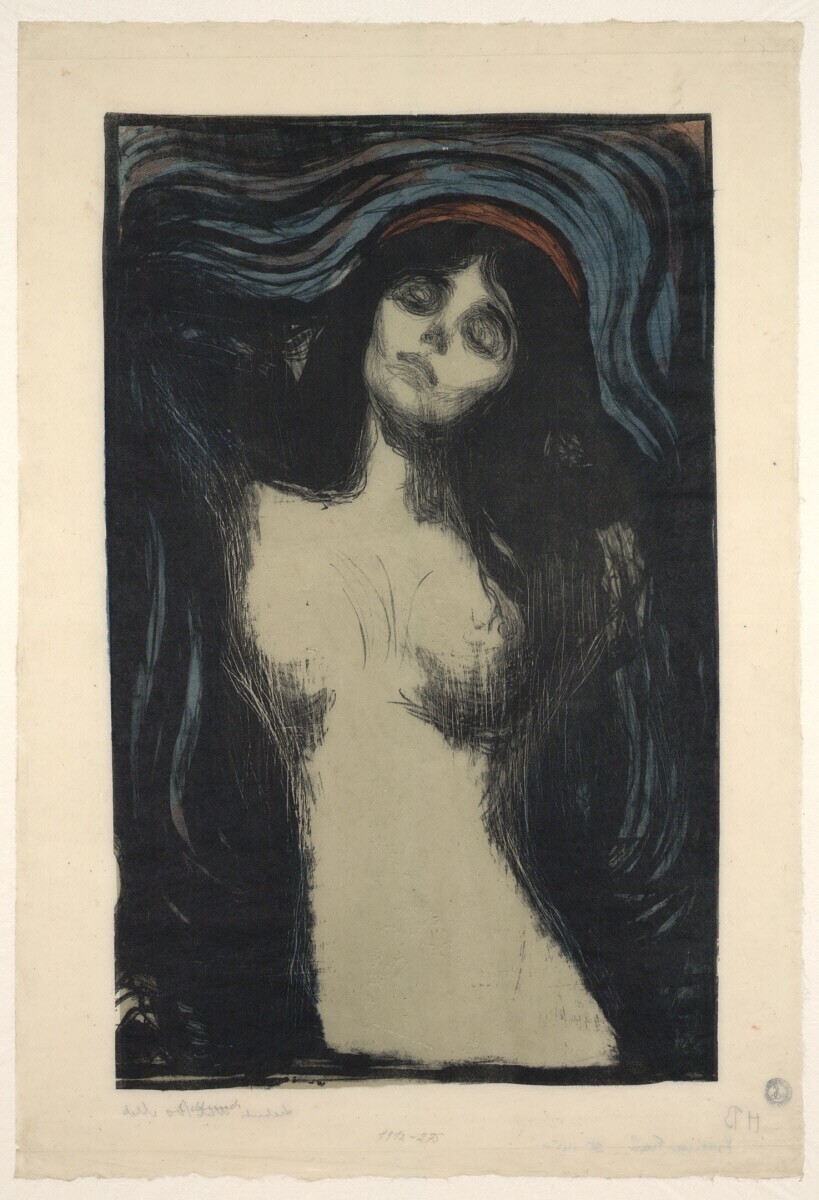

“Considered to have one of the best collections of drawings and prints in the world,” says Medievalists.net, the Albertina boasts “a large collection of works by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), a German artist who was famous for his woodcut prints and a variety of other works.” Here on Open Culture we’ve previously featured the genius of Dürer as revealed by his famed self-portraits. We’ve also featured visual exegeses of the art of Vienna’s own Gustav Klimt as well as Edvard Munch, two more recent European artists of great (and indeed still-growing) repute, works from both of whom you’ll find available to download in the Albertina’s online archive.

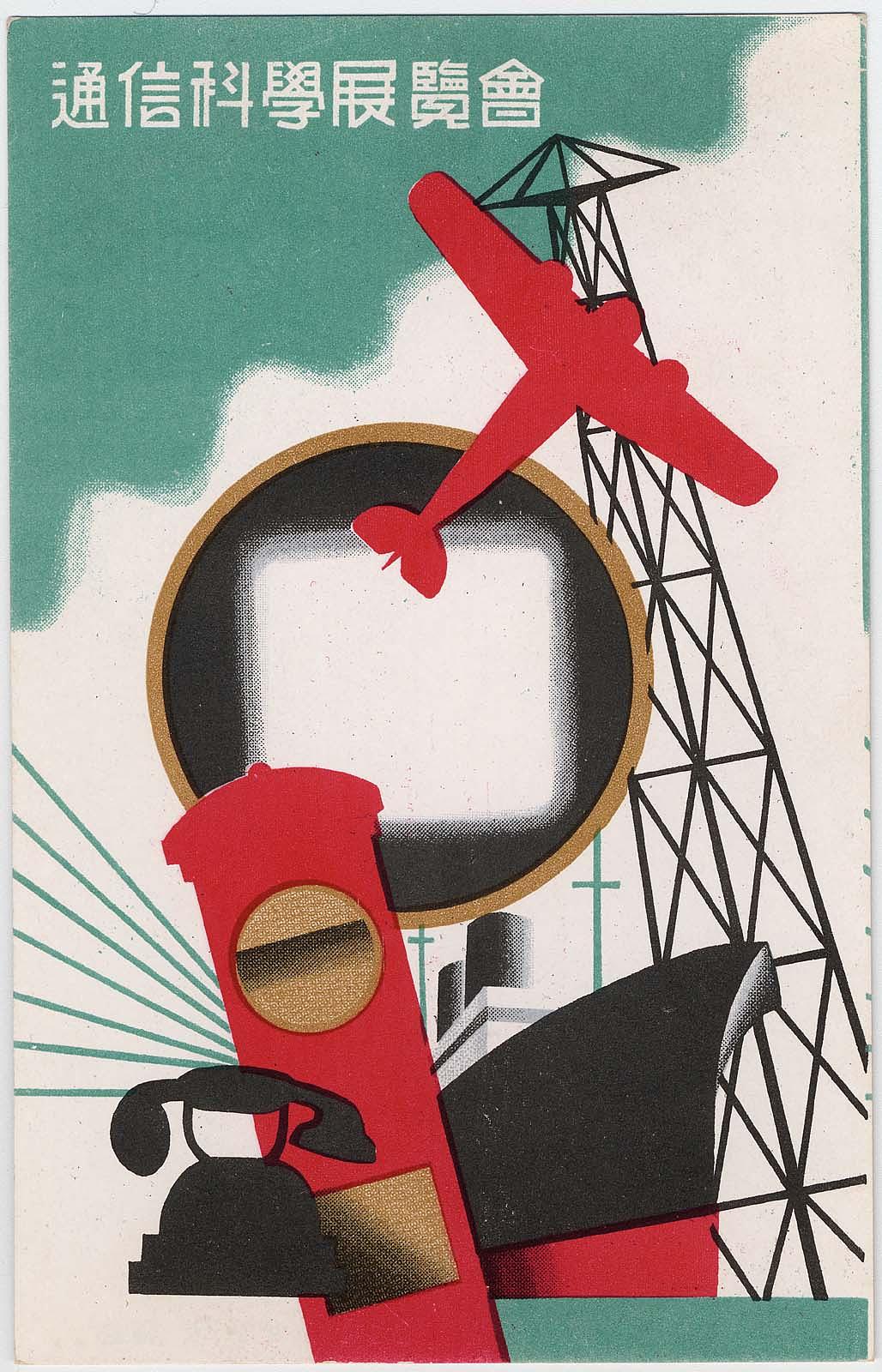

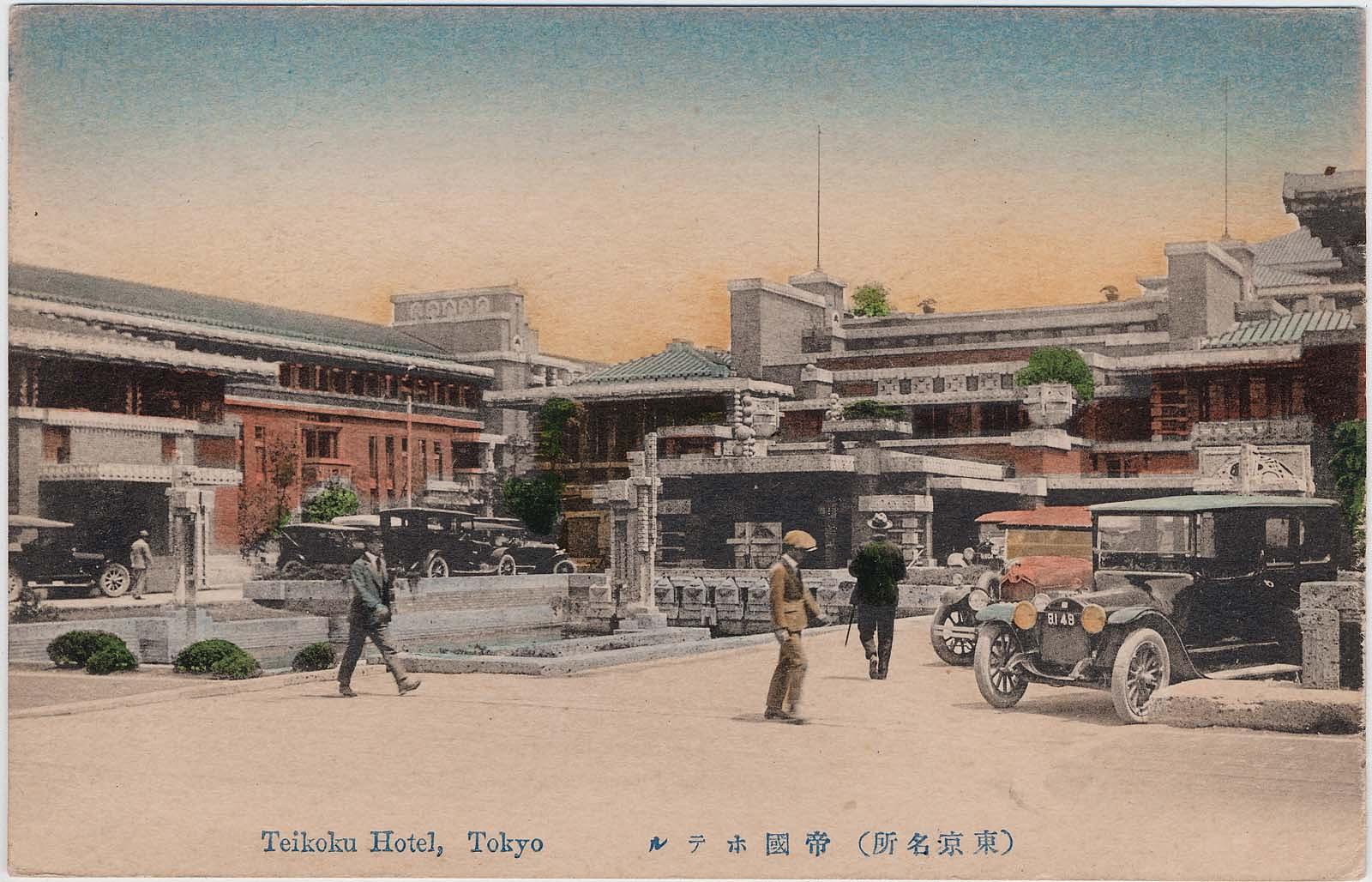

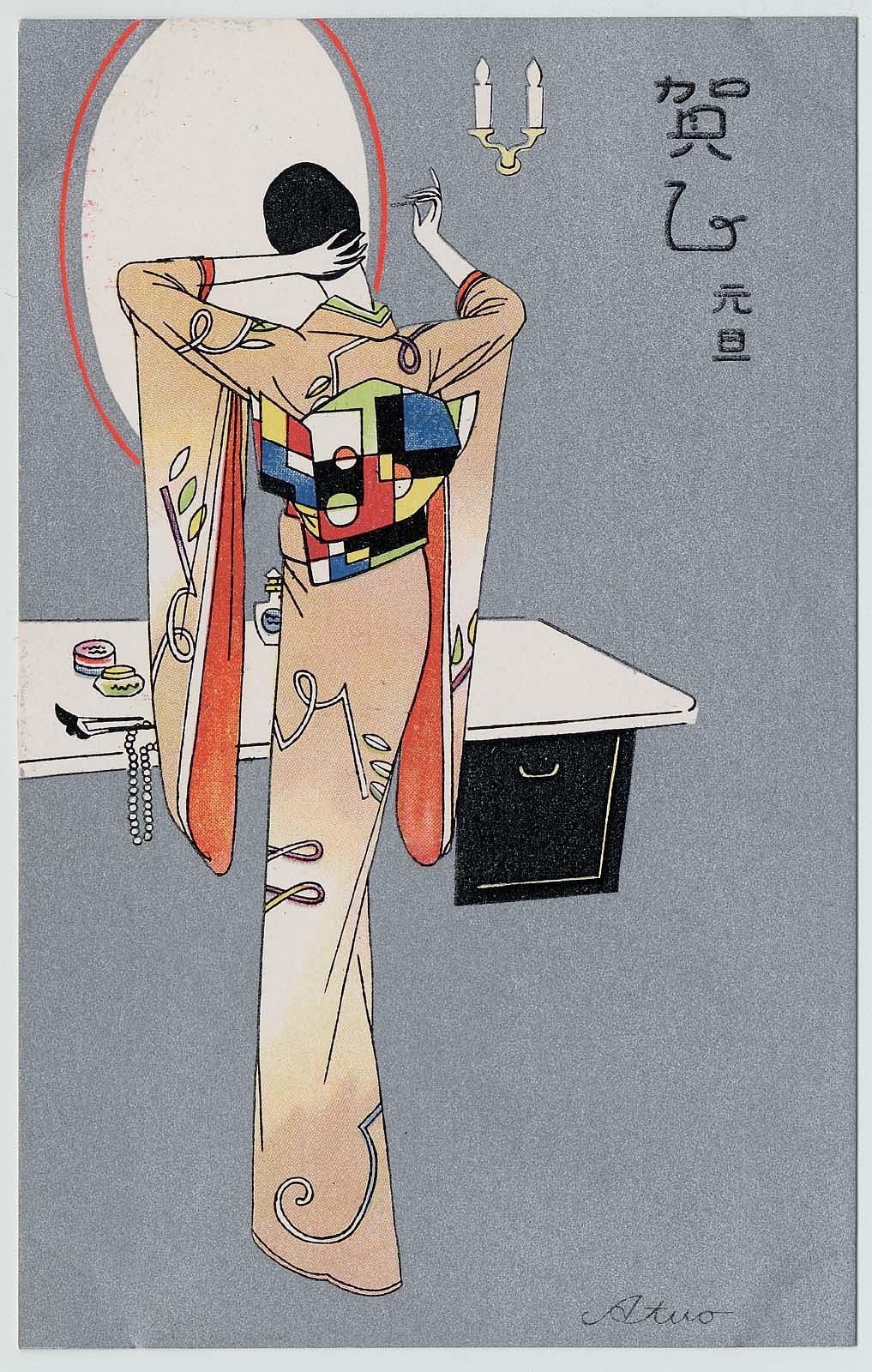

Those interested in the development of Dürer, Klimt, Munch, and other European masters will especially appreciate the Albertina’s online offerings. As an institution renowned for its large print room and collections of drawings, the museum has made available a great many sketches and studies, some of which clearly informed the iconic works we all recognize today. But there are also complete works as well, on which you can focus by clicking the “Highlights” checkbox above your search results. To understand Europe, you’d do well to begin in Vienna; to understand Europe’s art — including its photography, its posters, and its architecture, each of which gets its own section of the archive — you’d do well to begin at the Albertina online.

via Medievalists.net

Related content:

The Genius of Albrecht Dürer Revealed in Four Self-Portraits

Explore 7,600 Works of Art by Edvard Munch: They’re Now Digitized and Free Online

30,000 Works of Art by Edvard Munch & Other Artists Put Online by Norway’s National Museum of Art

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.