Last month, we delved into a proposal to use digital technology to clone the 2,500-year-old Parthenon Marbles currently housed in the British Museum.

The hope is that such uncanny facsimiles might finally convince museum Trustees and the British government to return the originals to Athens.

Today, we’ll take a closer look at just how these treasures of antiquity, known to many as the Elgin marbles, wound up so far afield.

The most obvious culprit is Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin, who initiated the takeover while serving as Britain’s ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1798–1803.

Prior to setting sail for this posting, he hatched a plan to assemble a documentary team who would sketch and create plaster molds of the Parthenon marbles for the eventual edification of artists and architects back home. Better yet, he’d get the British government to pay for it.

The British government, eying the massive price tag of such a proposal, passed.

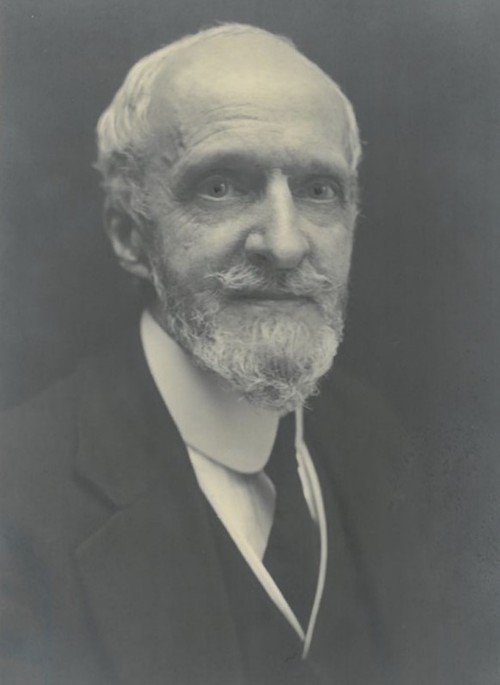

So Elgin used some of his heiress wife’s fortune to finance the project himself, hiring landscape painter Giovanni Battista Lusieri — described by Lord Byron as “an Italian painter of the first eminence” — to oversee a team of draftsmen, sculptors, and architects.

As The Nerdwriter’s Evan Puschak notes above, political alliances and expansionist ambition greased Lord Elgin’s wheels, as the Ottoman Empire and Great Britain found common cause in their hatred of Napoleon.

British efforts to expel occupying French forces from Egypt generated good will sufficient to secure the requisite firman, a legal document without which Lusieri and the team would not have been given access to the Acropolis.

The original firman has never surfaced, and the accuracy of what survives — an English translation of an Italian translation — casts Elgin’s acquisition of the marbles in a very dubious light.

Some scholars and legal experts have asserted that the document in question is a mere administrative letter, since it apparently lacked the signature of Sultan Selim III, which would have given it the contractual heft of a firman.

In addition to giving the team entry to Acropolis grounds to sketch and make plaster casts, erect scaffolding and expose foundations by digging, the letter allowed for the removal of such sculptures or inscriptions as would not interfere with the work or walls of the Acropolis.

This implies that the team was to limit itself to windfall apples, the result of the heavy damage the Acropolis sustained during a 1687 mortar attack by Venetian forces.

Some of the dislodged marble had been harvested for building materials or souvenirs, but plenty of goodies remained on the ground for Elgin and company to cart off.

In an article for Smithsonian Magazine, Hellenist author Bruce Clark details how Elgin’s personal assistant, clergyman Philip Hunt, leveraged Britain’s support of the Ottoman Empire and anti-France position to blur these boundaries:

Seeing how highly the Ottomans valued their alliance with the British, Hunt spotted an opportunity for a further, decisive extension of the Acropolis project. With a nod from the sultan’s representative in Athens—who at the time would have been scared to deny a Briton anything—Hunt set about removing the sculptures that still adorned the upper reaches of the Parthenon. This went much further than anyone had imagined possible a few weeks earlier. On July 31, the first of the high-standing sculptures was hauled down, inaugurating a program of systematic stripping, with scores of locals working under Lusieri’s enthusiastic supervision.

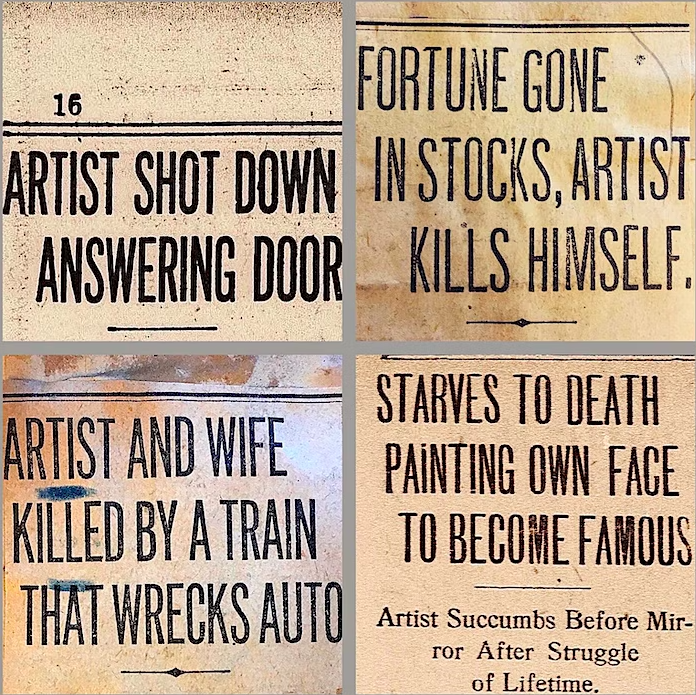

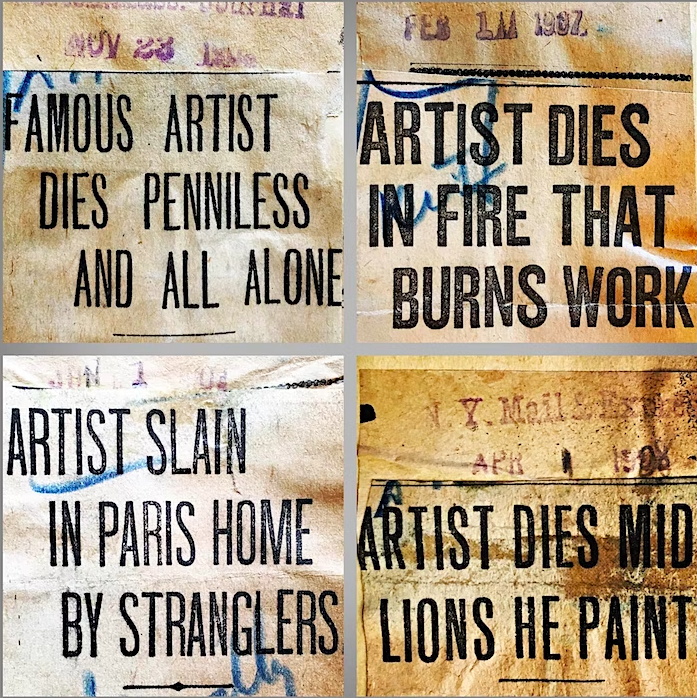

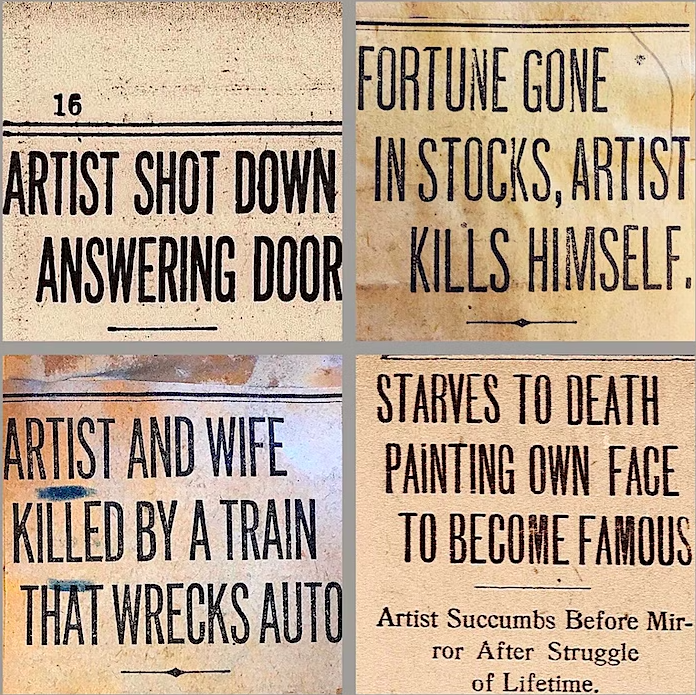

Lusieri, whose admirer Lord Byron became a furious critic of Elgin’s removal of the Parthenon marbles, ended his days believing that his commitment to Lord Elgin ultimately cost him an illustrious career as a watercolorist.

He also conceded that the team had been “obliged to be a little barbarous”, a gross understatement when one considers their vandalism of the Parthenon during the ten years it took them to make off with half of its surviving treasures — 21 figures from East and West pediments, 15 metope panels, and 246 feet of what had been a continuous narrative frieze.

Clark notes that although Elgin succeeded in relocating them to British soil, he “derived little personal happiness from his antiquarian acquisitions.”

After numerous logistical headaches involved in their transport, he found himself begging the British government to take them off his hands when an acrimonious divorce landed him in financial straits.

This time the British government agreed, acquiring the lot for £35,000 — less than half of what Lord Elgin claimed to have shelled out for the operation.

The so-called Elgin Marbles became part of the British Museum’s collection in 1816, five years before the Greek War of Independence’s start.

They have been on continual display ever since.

The 21st-century has witnessed a number of world class museums rethinking the provenance of their most storied artifacts. In many cases, they have elected to return them to their land of origin.

Greece has long called for the Parthenon marbles in the British Museum to be permanently repatriated to Athens, but thusfar museum Trustees have refused.

In their opinion, it’s complicated.

Is it though? Lord Elgin’s ultimate motivations might have been, and Bruce Clark, in a brilliant ninja move, suggests that the return could be viewed as a positive stripping away, atonement by way of getting back to basics:

Suppose that among his mixture of motives—personal aggrandizement, rivalry with the French and so on—the welfare of the sculptures actually had been Elgin’s primary concern. How could that purpose best be served today? Perhaps by placing the Acropolis sculptures in a place where they would be extremely safe, extremely well conserved and superbly displayed for the enjoyment of all? The Acropolis Museum, which opened in 2009 at the foot of the Parthenon, is an ideal candidate; it was built with the goal of eventually housing all of the surviving elements of the Parthenon frieze…. If the earl really cared about the marbles, and if he were with us today, he would want to see them in Athens now.

Related Content

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Restores the Original Colors to Ancient Statues

John Oliver’s Show on World-Class Art Museums & Their Looted Art: Watch It Free Online

Take a Virtual Reality Tour of the World’s Stolen Art

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.