If you’ve ever lived in a metropolis like London or New York, you know the sometimes-disorienting feeling of experiencing several decades—or centuries—at once in the dizzying accretions of architecture, street, and park designs. Or, at least, if you’ve toured one of those cities with a longtime resident, you’ve heard them loudly complain about how everything has changed. Whether you study urban life as a historian or a city dweller, you know well that change is constant in the story of big cities.

The animations here illustrate the point on a grand scale, with a satellite’s‑eye view of New York, above, from 1609 when the city was first built on Lenape land to its current configuration of five boroughs, dense thickets of high-rises, a massive, complex transportation system, and 8,600,000 residents. It ends with a quote from E.B. White that sums up the geography and vibrancy of Manhattan: “The city is like poetry: it compresses all life, all races, and breeds, into a small island and adds music and the accompaniment of internal engines.”

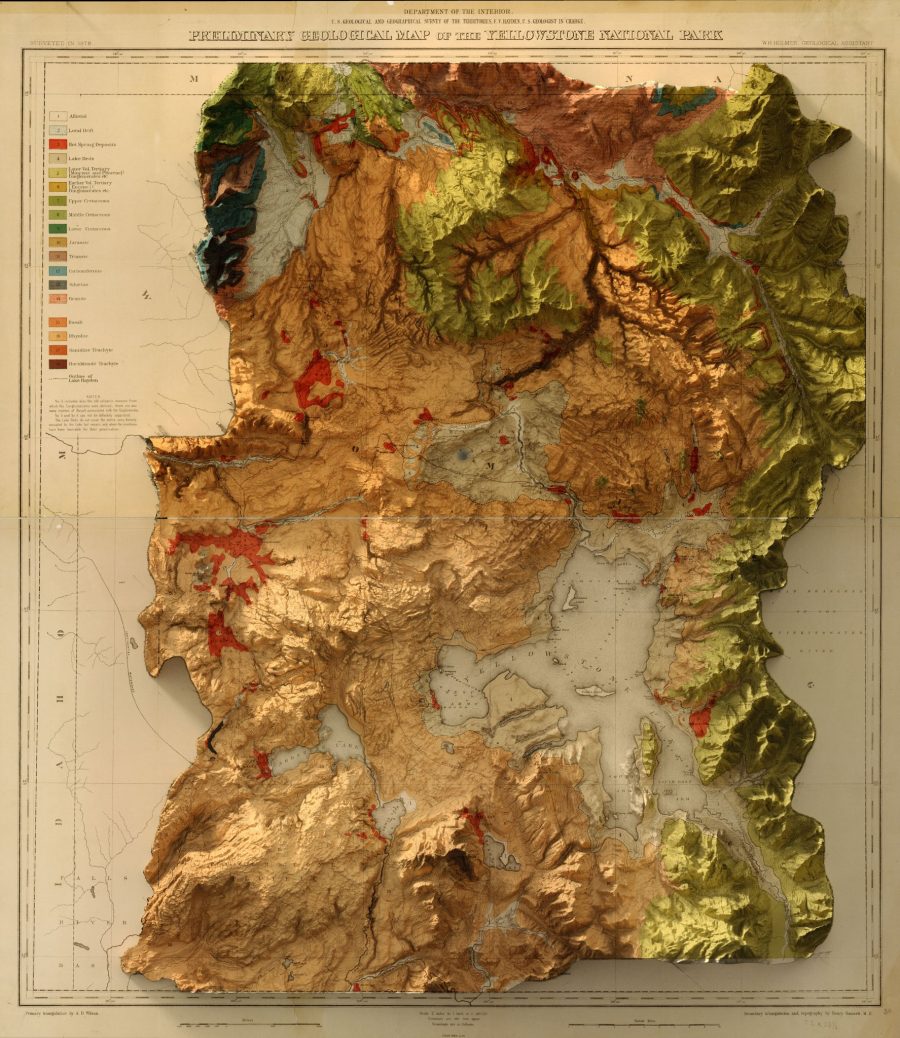

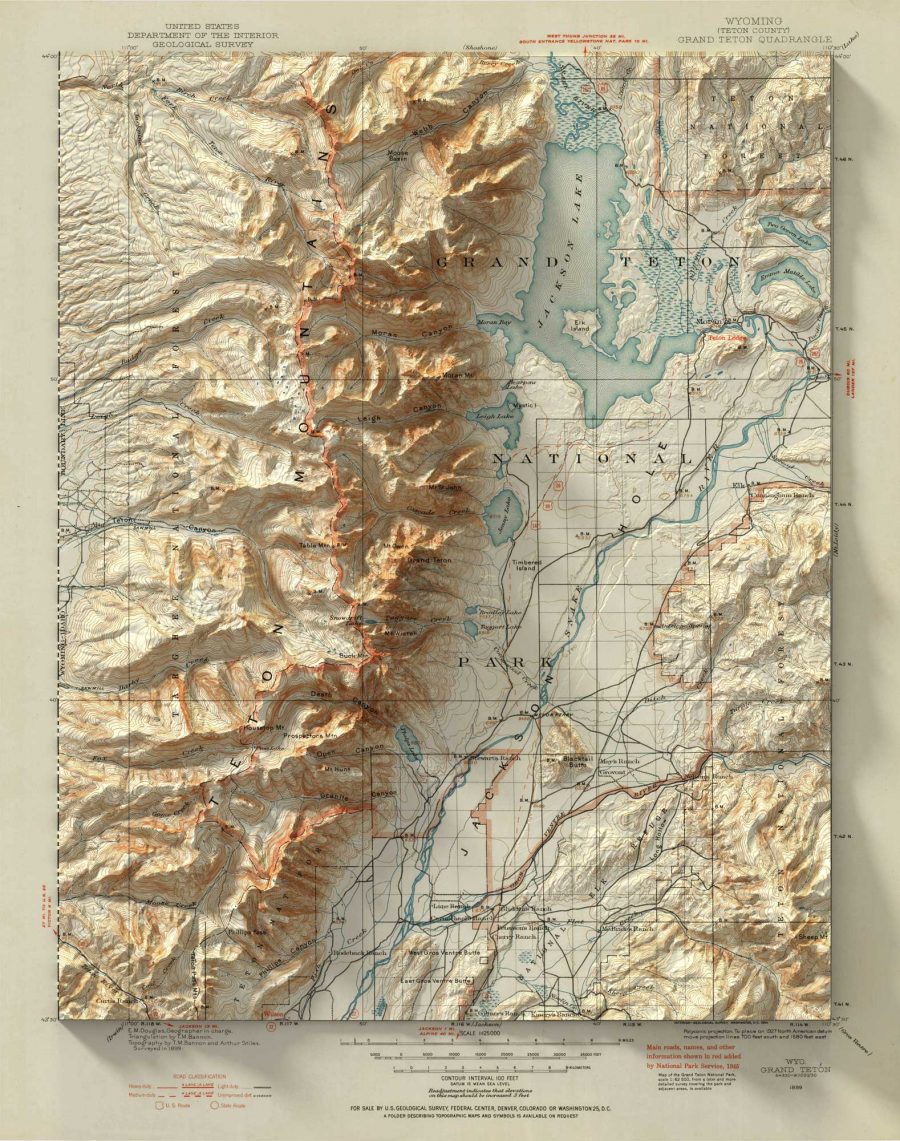

The New York video “animates the development of this city’s street grid and infrastructure systems,” writes its creator Myles Zhang at Here Grows New York City, “using geo-referenced road network data, historic maps, and geological surveys” to give us “cartographic snapshots” of every 20–30 years. Another project, the London Evolution Animation, uses similar techniques. But, of course, it reaches much further back in time, to over 2000 years ago when the Romans built the first road system across England and the port of Londinium.

Created in 2014, the visualization shows how the city evolved, “from its creation as a Roman city in 43AD to the crowded, chaotic megacity we see today.” As designers Flora Roumpani and Polly Hudson describe at The Guardian, the project drew from several sources, including the Museum of London Archaeology and the University of Cambridge’s engineering department. From these two institutions came “datasets from the Roman and Medieval periods as well as the 17th and early 18th centuries,” and “road network datasets from the late 18th century to today.”

Other archives offered information on the city’s historical buildings and monuments. Captions and a timeline provide a handy guide through its long history, as we watch more and more roads and buildings appear (and disappear after the Great Fire). These videos are useful references for students of urbanism, and they might give some perspective to the New Yorker or Londoner in your life who can’t stop talking about how much the city’s changed. Just imagine what these megacities could look like in another few hundred years.

Related Content:

Immaculately Restored Film Lets You Revisit Life in New York City in 1911

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness