Fantasy fiction invariably includes a map for readers to understand the hero’s journey, literally. We know that Hobbits had to walk a long way into Mordor, but seeing it cartographically really hits home. But what of the great road trip novels, where the country is America, the journey is long and often circular, and self-actualization awaits the hero, and not an army of orcs?

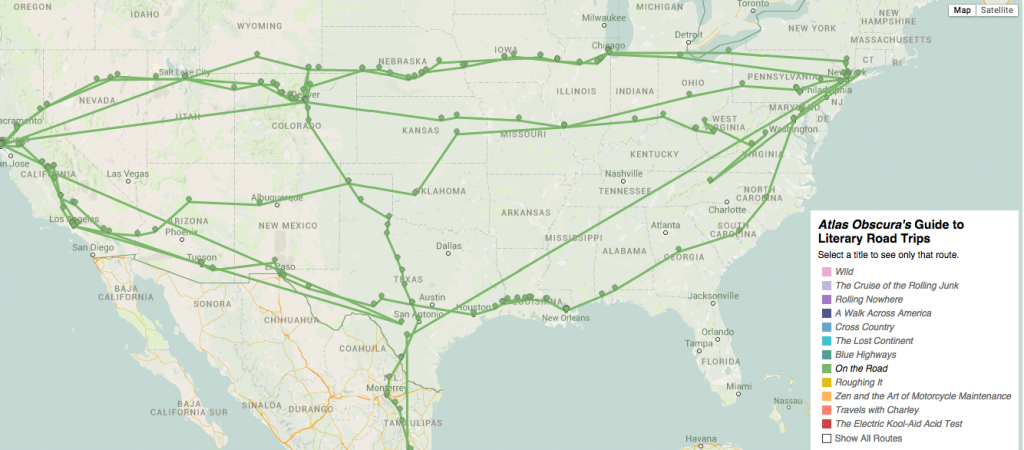

Atlas Obscura, Joshua Foer and Dylan Thuras’ blog of discovery and adventure in the modern world, have come to the rescue with an interactive map that plots out the travels of road trip-filled books, some non-fiction, others fictionalized reality. Where a location is mentioned in a text, it has been pinned to the map, and by clicking on the pin, the relevant text is revealed. Clever stuff.

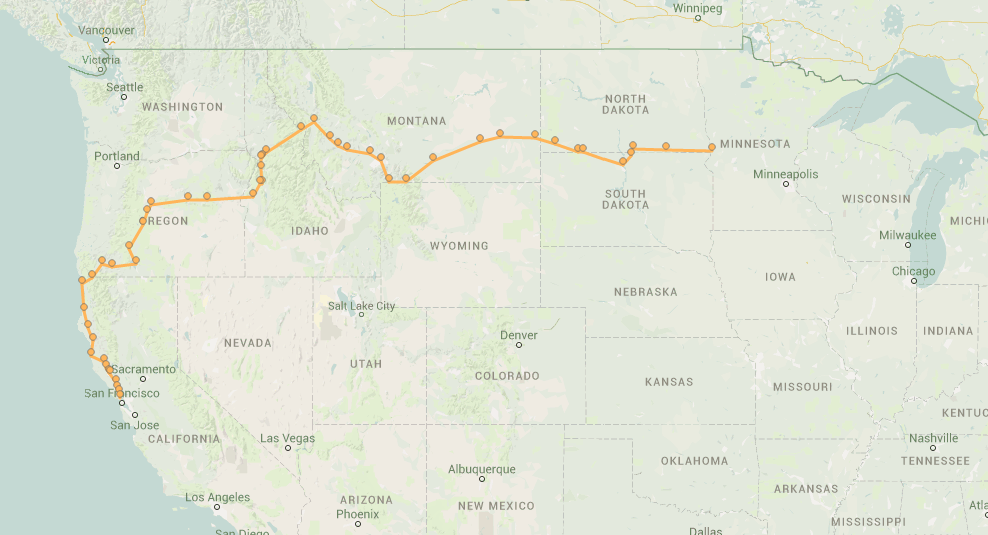

For example, the map for Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (see snapshot above) plots out the five trips contained in the novel, and one can see the main hubs of the story: NYC and San Francisco, of course, but also Denver and the crazed detour town to Mexico City, where Sal, Dean, and Stan Shephard party hard in a bordello and Sal winds up with dysentery for his troubles.

For something more straightforward, check out the Northwest travels at the heart of Robert M. Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Written in the first person, the novel’s narrator travels by motorcycle with his son from Minnesota to Northern California, ending up in San Francisco, taking 17 days. The philosophical journey, however, covers wider terrain.

Another Bay Area tale, Tom Wolfe’s account of Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test starts in La Honda, California, a mountain getaway to the west of San Jose, and, as one can see, completes a circle of the States, including trips to both Calgary, Canada and Manzanillo, Mexico, where everybody is “uptight,” man, heading northeast to both Guanajuato and Aguascalientes, where Acid Tests are administered.

There’s more at the link, including maps for Wild, A Walk Across America, and Travels with Charley. It might inspire a repeat reading of a favorite book. Or it might inspire you to just light out for the territories.

Related Content:

The Acid Test Reels: Ken Kesey & The Grateful Dead’s Soundtrack for the 1960s Famous LSD Parties

Jack Kerouac Reads from On the Road (1959)

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the FunkZone Podcast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.