Anyone who loves cities almost certainly loves transit maps: for well over a century, they’ve not only played an essential role in the navigation of urban spaces but developed into their very own distinctive form at the intersection of utility and aesthetics. The finest examples simultaneously possess the clarity and information-richness of the best graphic design and hold out promises of excitement and modernity that require a true artistic sensibility to properly express. None of this is lost on Cameron Booth, the Australian graphic designer living in Portland, Oregon who runs the site Transit Maps.

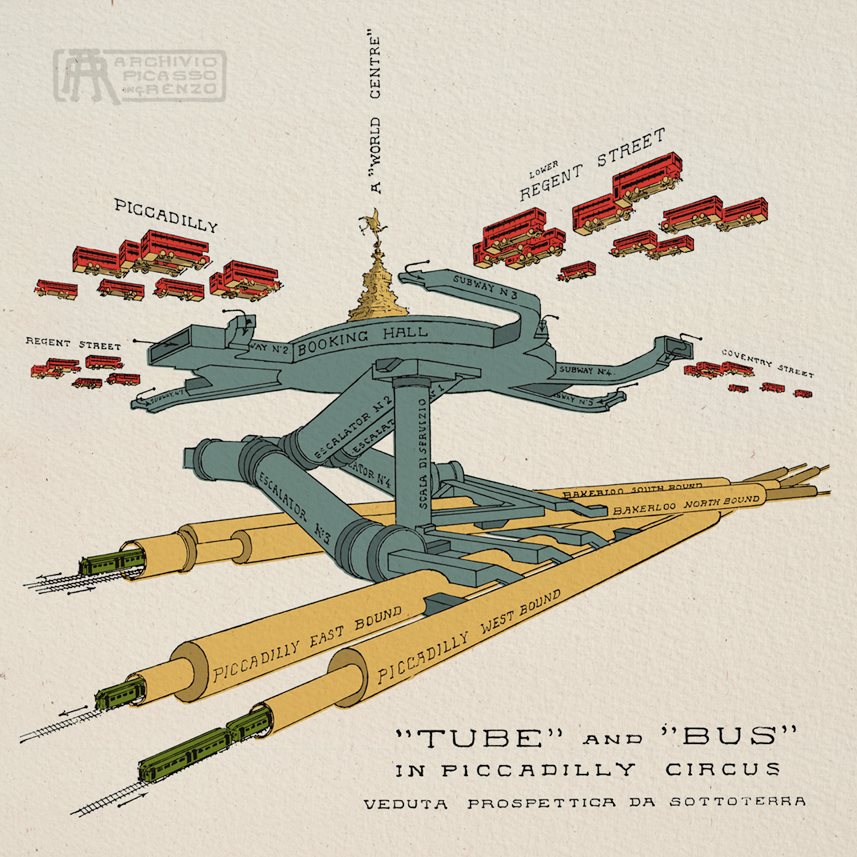

“A well designed transit map conveys a lot of information in a very small space,” writes Booth on the site’s About page. “In an instant, we learn how to get from ‘A’ to ‘B’, simply by following some coloured lines. The very best maps become symbols of their city, admired and loved by all.” None have become quite so symbolic as the map of the London Underground, the oldest subway system in the world, and Transit Maps’ posts filed under the London Underground tag, such as the 1929 cutaway diagram of its Piccadilly Circus station by Italian architect and urban designer Renzo Picasso just above provide plenty of good reading — and even better viewing — for its many enthusiasts.

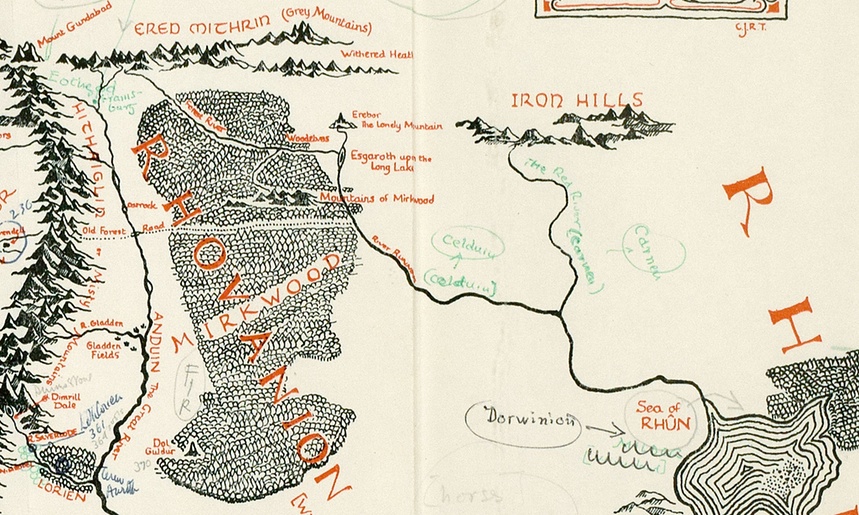

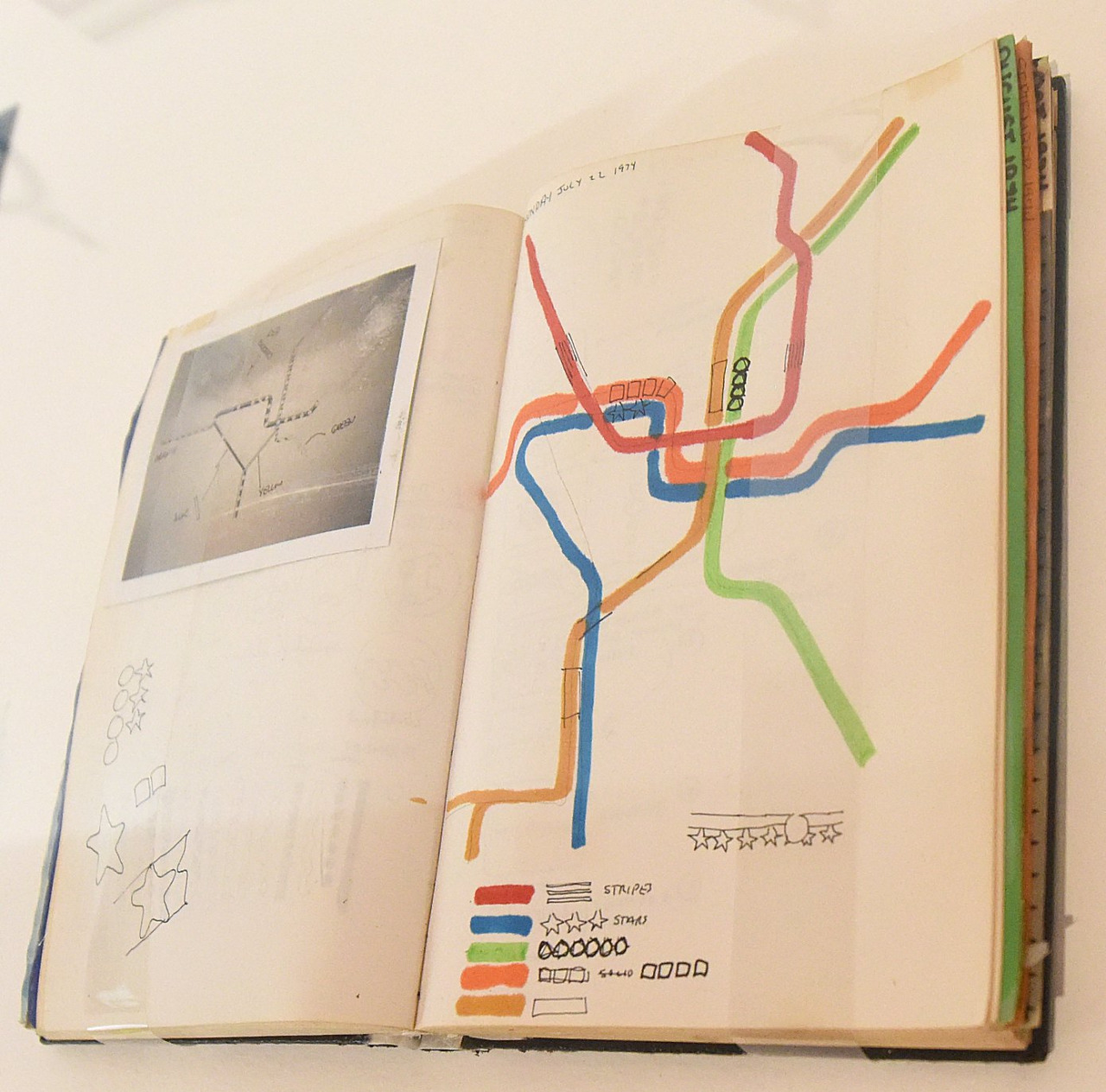

Among American cities, no subway system has a more respected map than Washington, DC’s, the work of graphic designer Lance Wyman, for whom it has remained a work in progress: he oversaw a redesign just five years ago, almost forty years after the system went into service and his original map made its debut. Here we have one of Wyman’s original working sketches for the map straight from his notebook. “Interestingly, it looks like Wyman was experimenting with textural treatments for the route lines at this time,” adds Booth, “an idea I’m ever so glad he abandoned, because it would have looked so busy and hideous.”

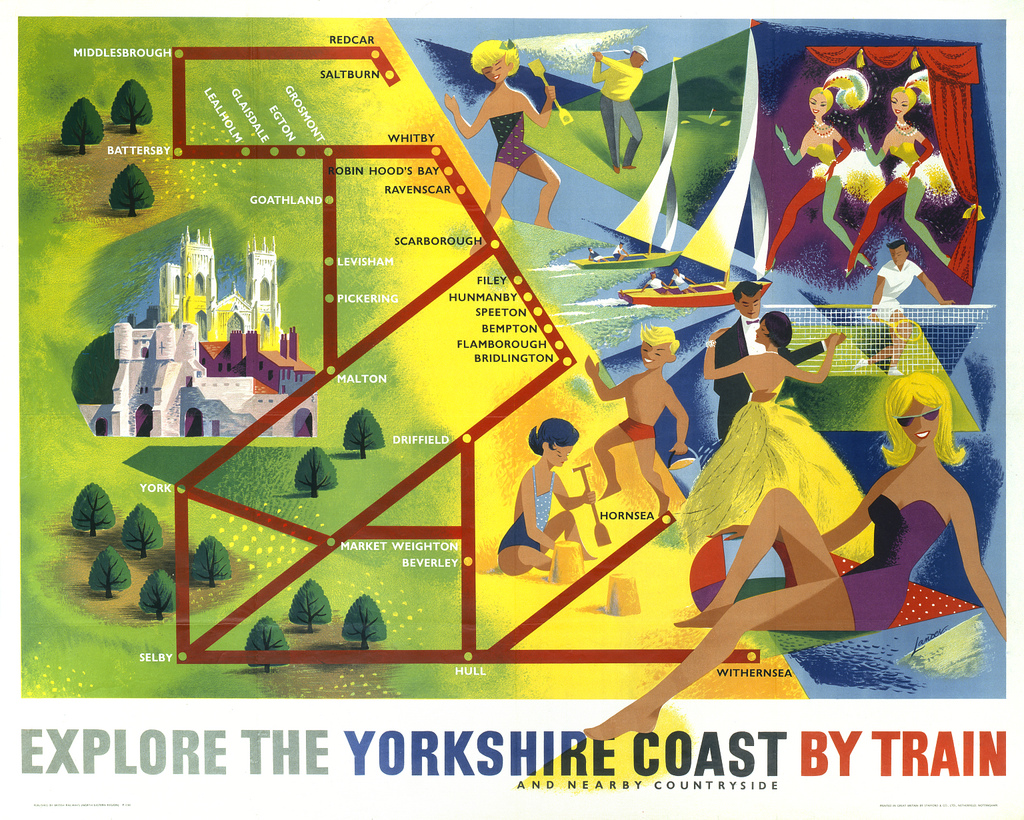

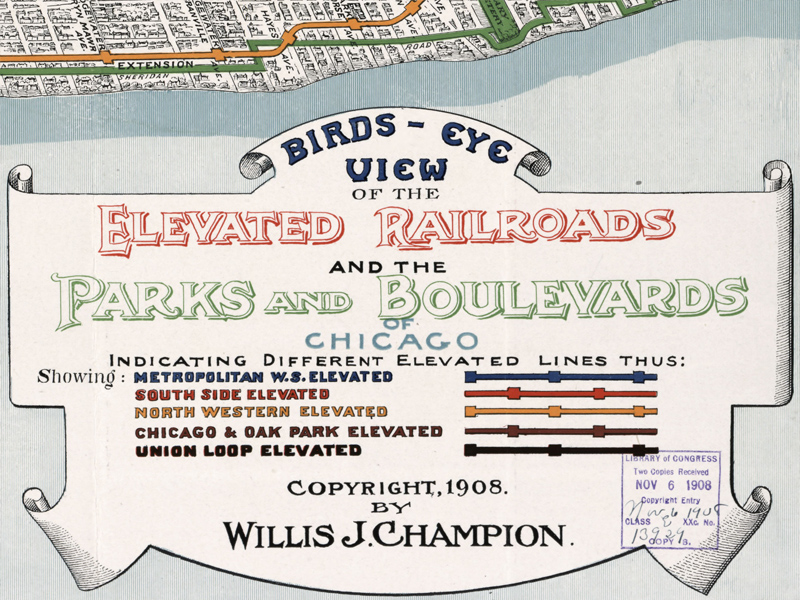

Having seen many more transit maps than most, and even having designed some of his own (including a reworking of the DC Metro map), Booth doesn’t hesitate to point out both the virtues and the flaws of the ones he posts. He even grades them on a star rating system (with, of course, circular London Underground logos substituting for actual stars), collecting the very best under the five-star tag. One such passage with flying colors, the 1950s Yorkshire coast train map at the top of the post, has Booth exclaiming that “they don’t make ‘em like this any more. The 1908 bird’s-eye view of Chicago, source of the legend above, scores its own five stars by “minute attention to detail,” down to the inclusion of “smoke curls from factory chimneys” and “almost every tree in the city’s parks.”

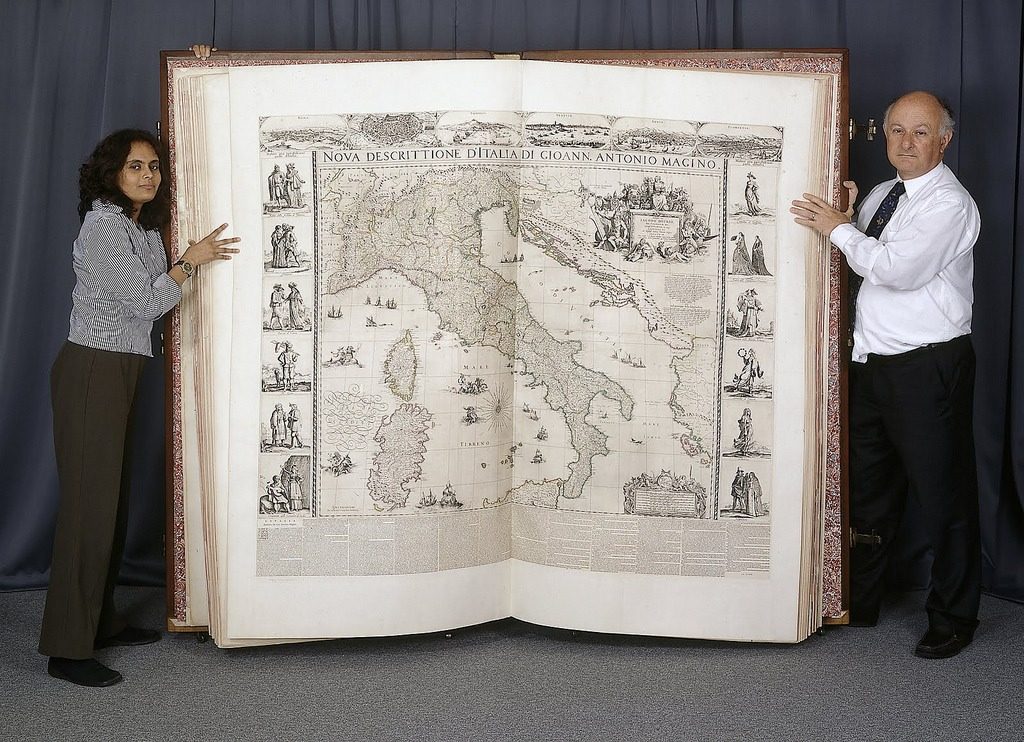

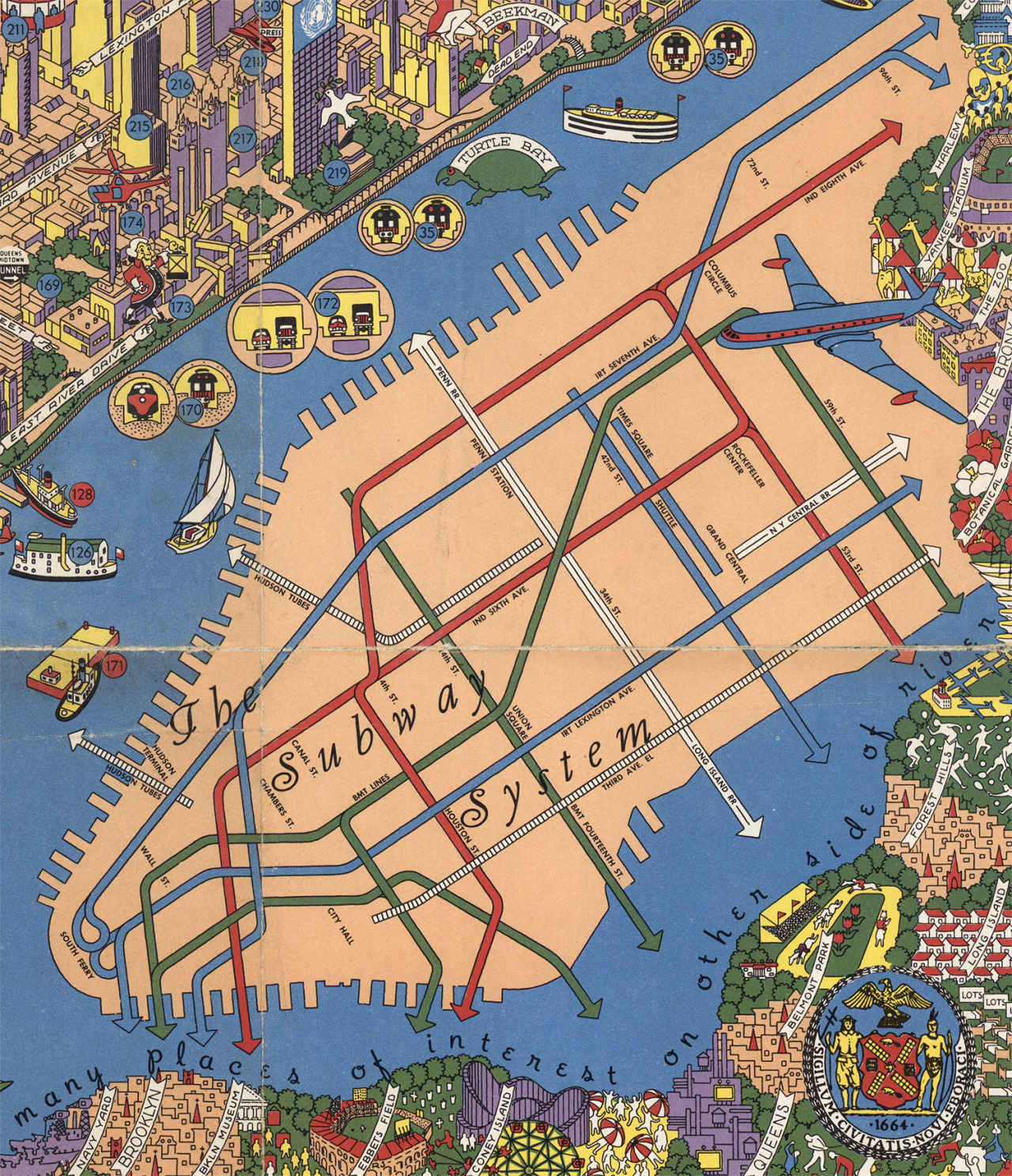

Few cities have attracted as much attention from mapmakers as New York, possibly due to all its wonders — or at least those are what IBM graphic designer Nils Hansell emphasizes in his mid-1950s map “Wonders of New York” which, despite not looking far past Manhattan, does include transit and much else besides: Booth mentions its depiction of “300-odd numbered points of interest” as well as “the last vestiges of New York’s once-extensive elevated railway lines.” You need quite a high-definition scan to really appreciate all this, and Booth found one in the David Rumsey Map Collection, which we’ve previously featured here on Open Culture.

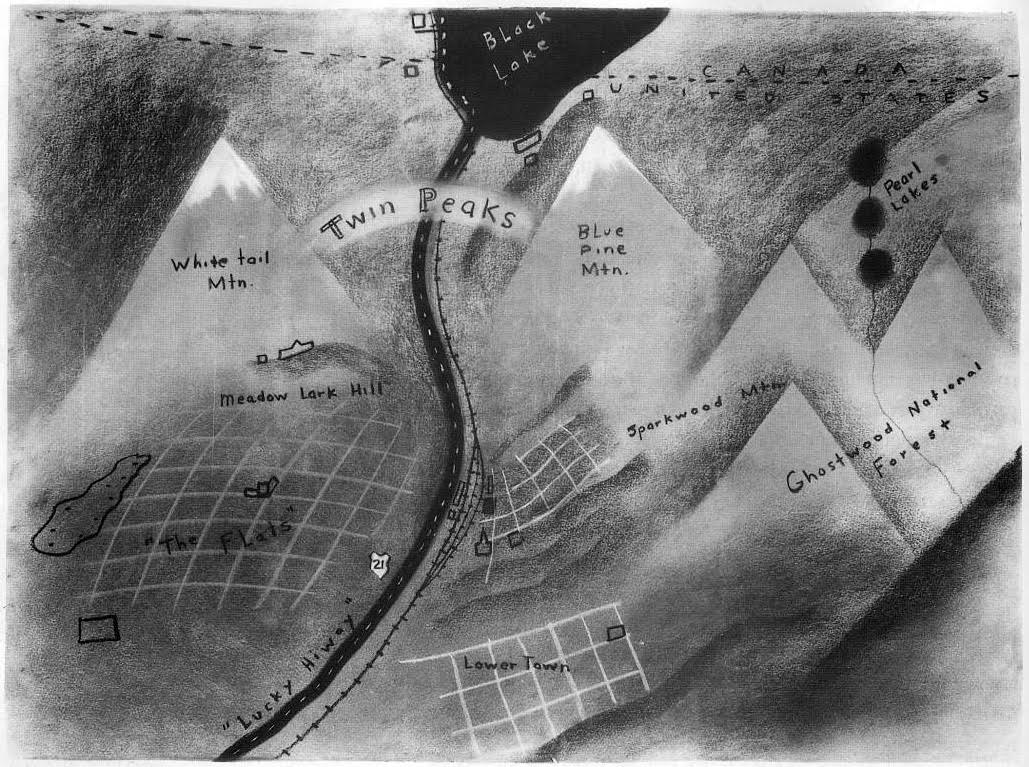

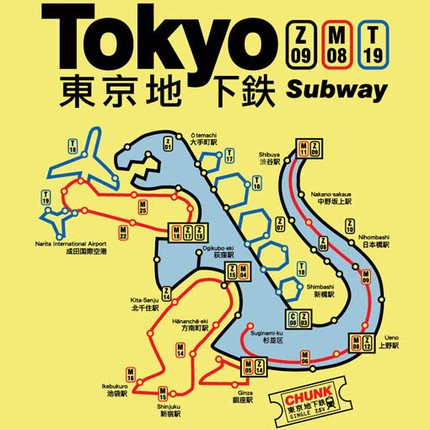

Scroll through the pages and pages of Transit Maps’ historical tag, and you’ll find a wealth of fascinating showpieces of the transit mapper’s art, not just from the Londons and New Yorks of the world, but also from times and places like Berlin in 1931, Madison, Wisconsin in 1975, and Booth’s own old hometown of Sydney in 1950 and new hometown of Portland in 1978. The archive even includes transit maps from unusual places, such as a delightful one printed on the back of a Japanese matchbox in the 1920s, and maps for transit systems never completed, such as the one for the Baghdad Metro from the early 1980s just above. Iraq’s capital may still await a full-service subway system — and much else besides — but at least its map earns top marks.

Related Content:

Designer Massimo Vignelli Revisits and Defends His Iconic 1972 New York City Subway Map

Vintage Video: A New York City Subway Train Travels From 14th St. to 42nd Street (1905)

Vladimir Nabokov Creates a Hand-Drawn Map of James Joyce’s Ulysses

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.