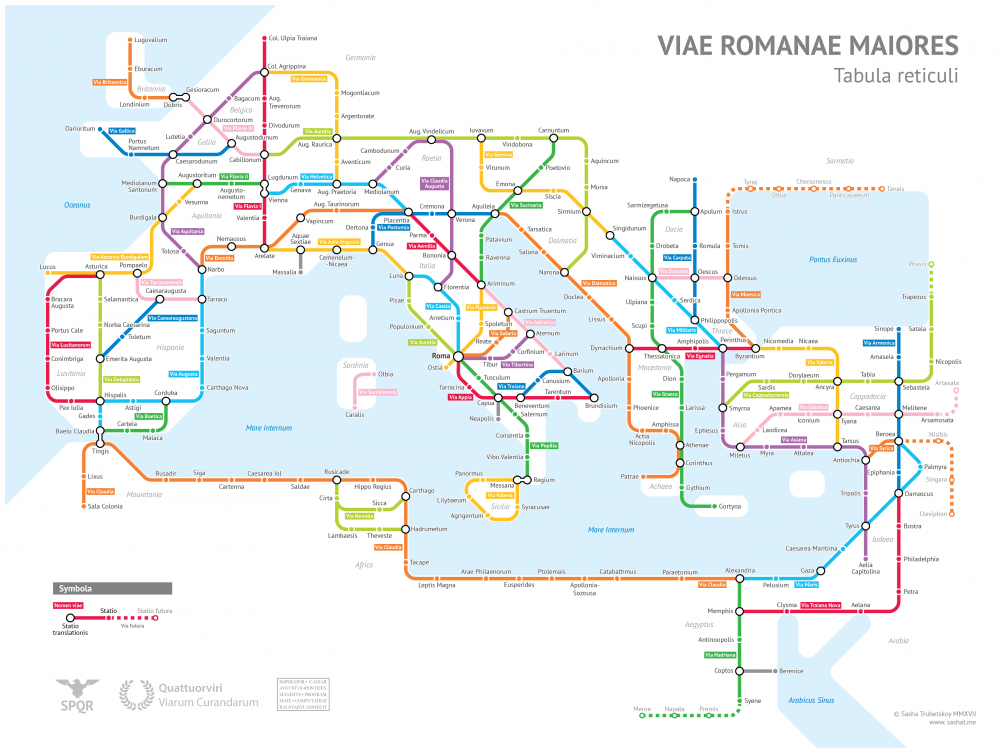

Walk around London with someone who knows its deep history — not hard to arrange, given the way London enthusiasts treat historical knowledge as a hypercompetitive sport — and you’ll have more than a few paths of “Roman roads” pointed out to you. Even in the city of Big Ben and Buckingham Palace, the Shard and the Gherkin, chicken shops and curry houses, there remain fragments and traces of the 2,000 miles of roads the Roman Army built between British towns and cities between 43 and 410 AD, Britain’s centuries as a province of the Roman Empire.

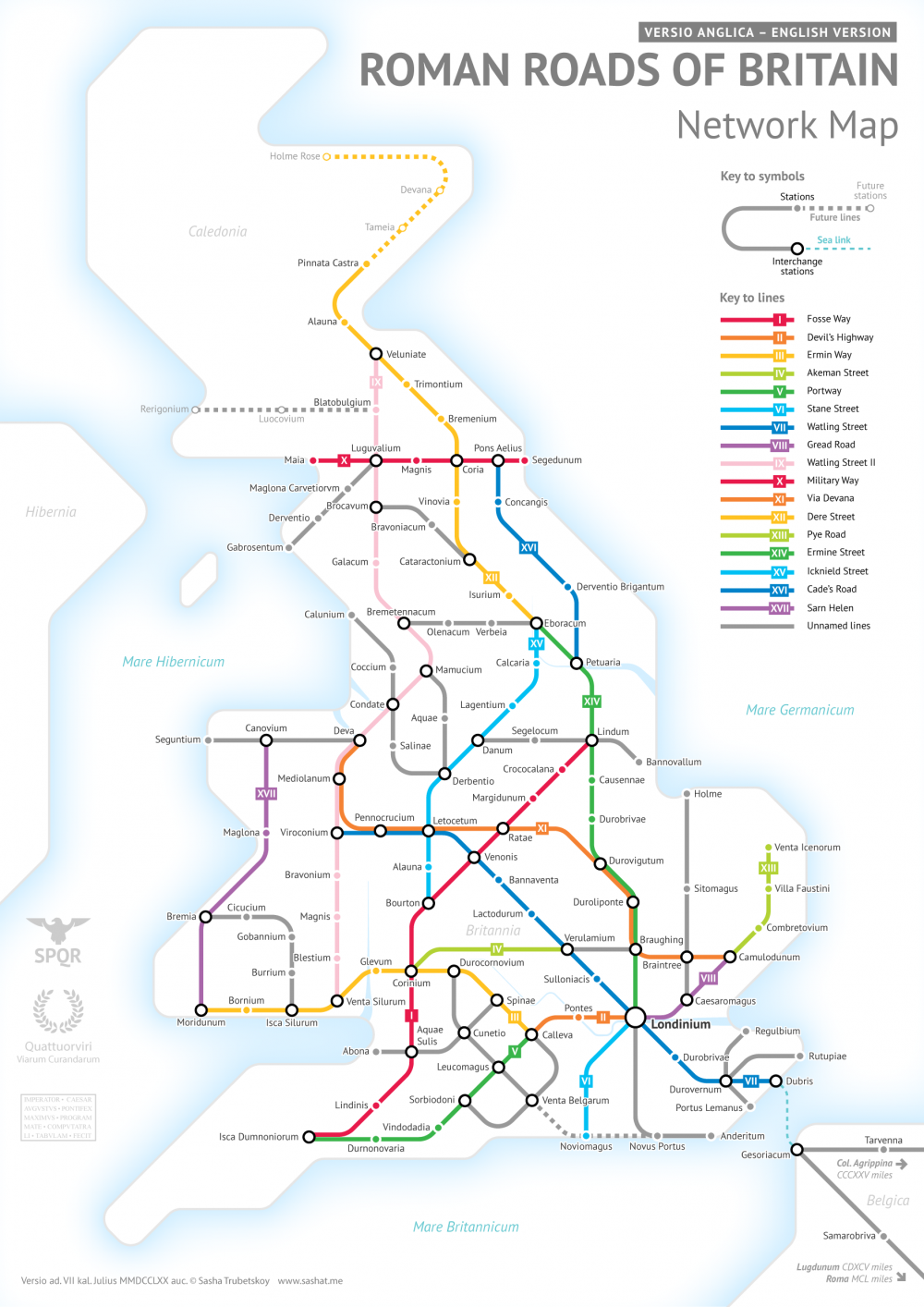

Though some of Britain’s Roman Roads have become modern motorways, most no longer exist in any form but those bits and pieces history buffs like to spot. This makes it difficult to get a sense of how they all ran and where — or at least it did until Sasha Trubetskoy made a Roman Roads of Britain Network Map in the graphic-design style of the subway maps you’ll find in London or any other major city today. Trubetskoy, an undergraduate statistics major at the University of Chicago, first found cartographical fame a few months ago with his “subway map” of roads across the entire Roman Empire circa 125 AD.

“Popular request,” he writes, demanded a Britain-specific follow up, a project he describes as “far more complicated than I had initially anticipated.” The challenges included not just the sheer number of Roman Roads in Britain but a lack of clarity about their exact location and extents. As in his previous map, Trubetskoy admits, “I had to do some simplifying and make some tough choices on which cities to include.” While this closer-up view demanded a more geographical faithfulness, he nevertheless “had to get rather creative with the historical evidence” in places, to the point of using such “not exactly Latin-sounding” names as “Watling Street” and “Ermin Way.”

Still, barring a revolutionary discovery in Roman history, you’re unlikely to find a more rigorous example of subway-mapped Roman Roads in Britain than this one. And for $9 USD you can have it as a “crisp PDF” suitable for printing as a poster and giving to anyone passionate about the history of Britain — or the history of Rome, or graphic design, or maps that aren’t what they might seem at first glance.

Related Content:

Ancient Rome’s System of Roads Visualized in the Style of Modern Subway Maps

Rome Reborn: Take a Virtual Tour of Ancient Rome, Circa 320 C.E.

The Rise & Fall of the Romans: Every Year Shown in a Timelapse Map Animation (753 BC ‑1479 AD)

A Wonderful Archive of Historic Transit Maps: Expressive Art Meets Precise Graphic Design

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.