I live in South Korea, but the South Koreans don’t call it South Korea. The country has its own language, of course, and that language has its own name for the country, daehan minguk (대한 민국), or more commonly hanguk (한국) — not that it stops the global branding-friendly letter K, which has made its way from “K‑pop” to “K‑beauty” to even (albeit much less successfully) things like “K‑food.” As far as our much-reported-on northern neighbor, South Koreans call it bukhan (북한), but its inhabitants call their land joseon minjujueui inmin gonghwaguk (조선민주주의인민공화국). And as with Korea South and North, so with every country in the world: each one has an endonym.

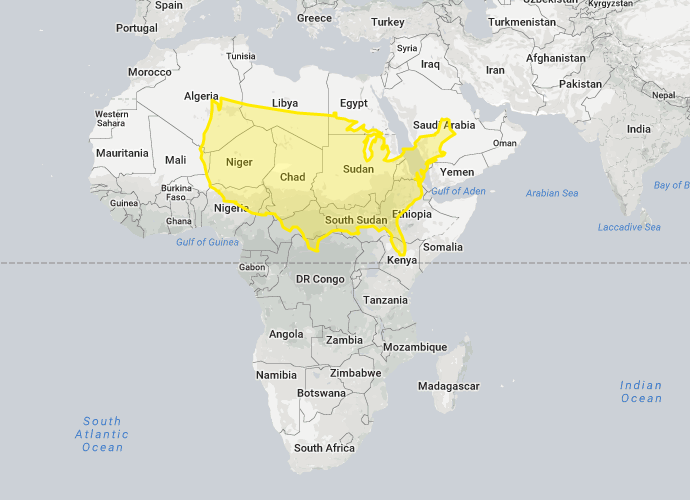

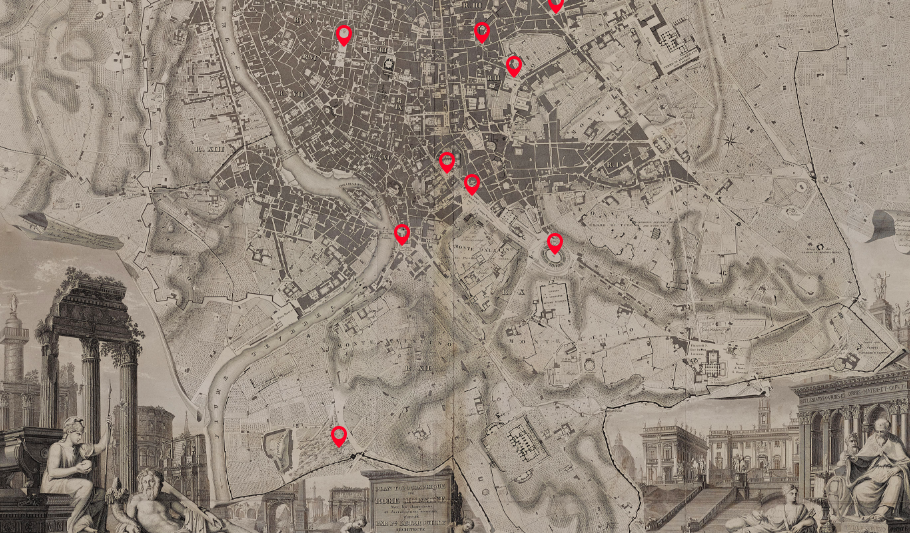

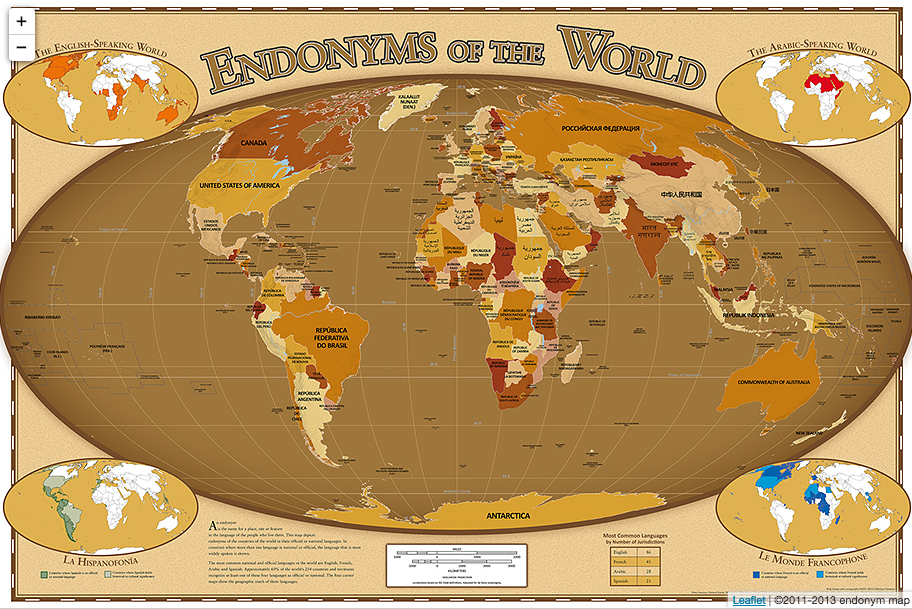

“An endonym is the name for a place, site or location in the language of the people who live there. These names may be officially designated by the local government or they may simply be widely used.” So says the front page of the Endonym Map, which labels every country (or disputed territory) in the world with its endonym, written in the language’s own script.

When you first learned the names of foreign countries, you actually learned their exonyms, their names in a foreign language: yours. “South Korea” and “North Korea” are exonyms, as are names like “Japan,” “Finland,” “Turkey,” and “France.” Nihon-koku (日本国), Suomen tasavalta, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, and la République française all appear on the Endonym Map, as do many other well-known countries you might at first glance assume you’ve never heard of.

The map’s creator notes that “the most common official or national language in the world is English, with 86 countries or territories,” which represents “one-third the number of total countries and approximately 30% of the planet’s land area.” Because of that, people all over the world do tend to know the English exonym for their own country, but that’s hardly an excuse not to learn its real name should you decide to pay them a visit. And that counts as the first step toward actually learning its language, a journey that the Foreign Service Institute’s language-learning map we featured last year can help you plan. Hwaiting, as we say here in the Koreanized English — or Englishized Korean? — of hanguk.

You can view the Endonym Map in a larger, zoomable format here.

Related Content:

The Favorite Literary Work of Every Country Visualized on a World Map

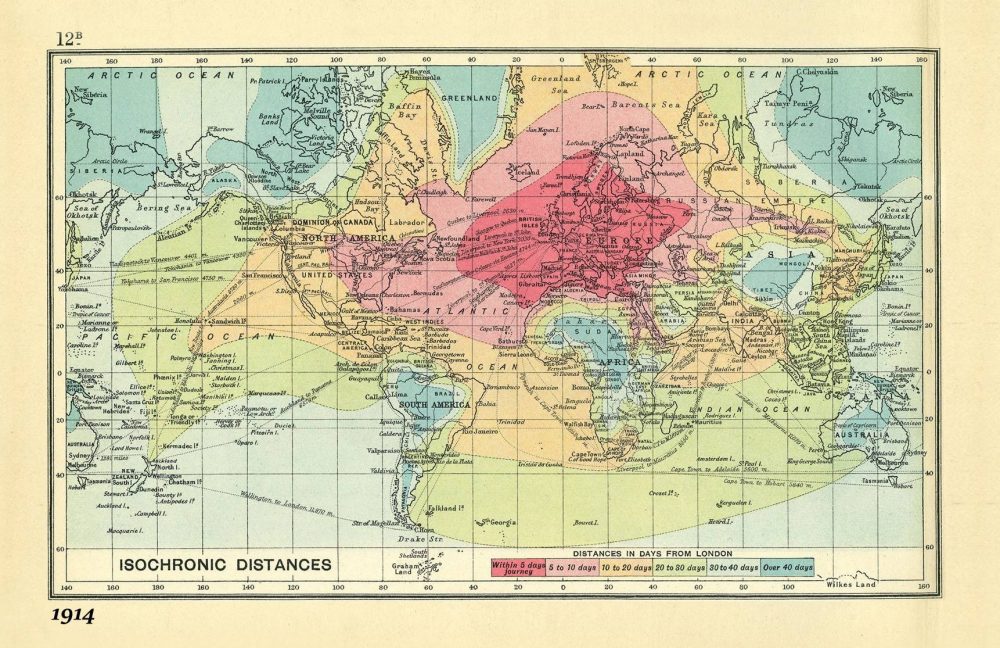

A Map Showing How Much Time It Takes to Learn Foreign Languages: From Easiest to Hardest

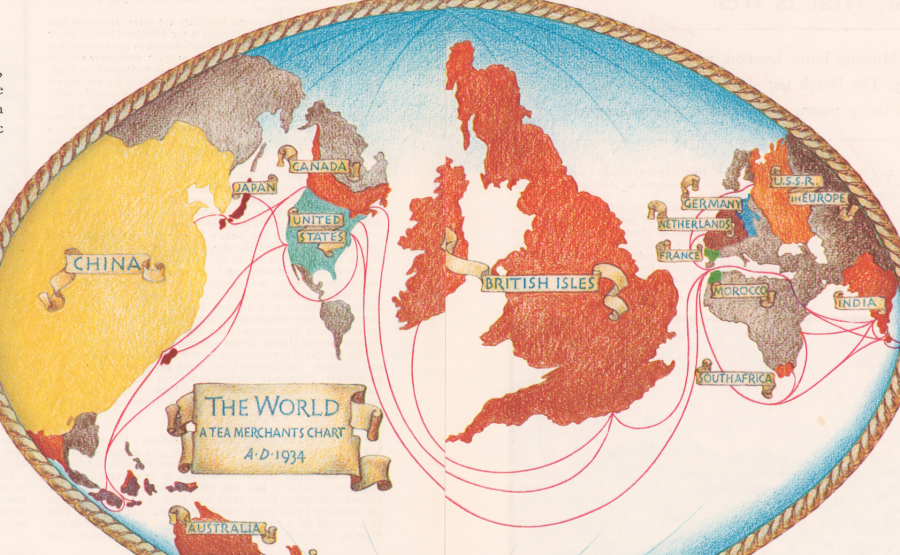

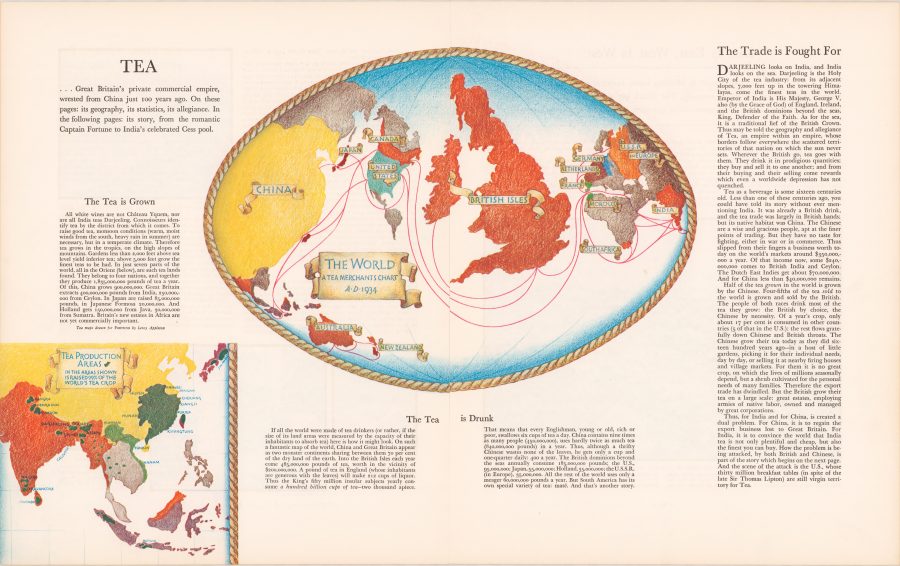

1934 Map Resizes the World to Show Which Country Drinks the Most Tea

“Every Country in the World”–Two Videos Tell You Curious Facts About 190+ Countries

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.