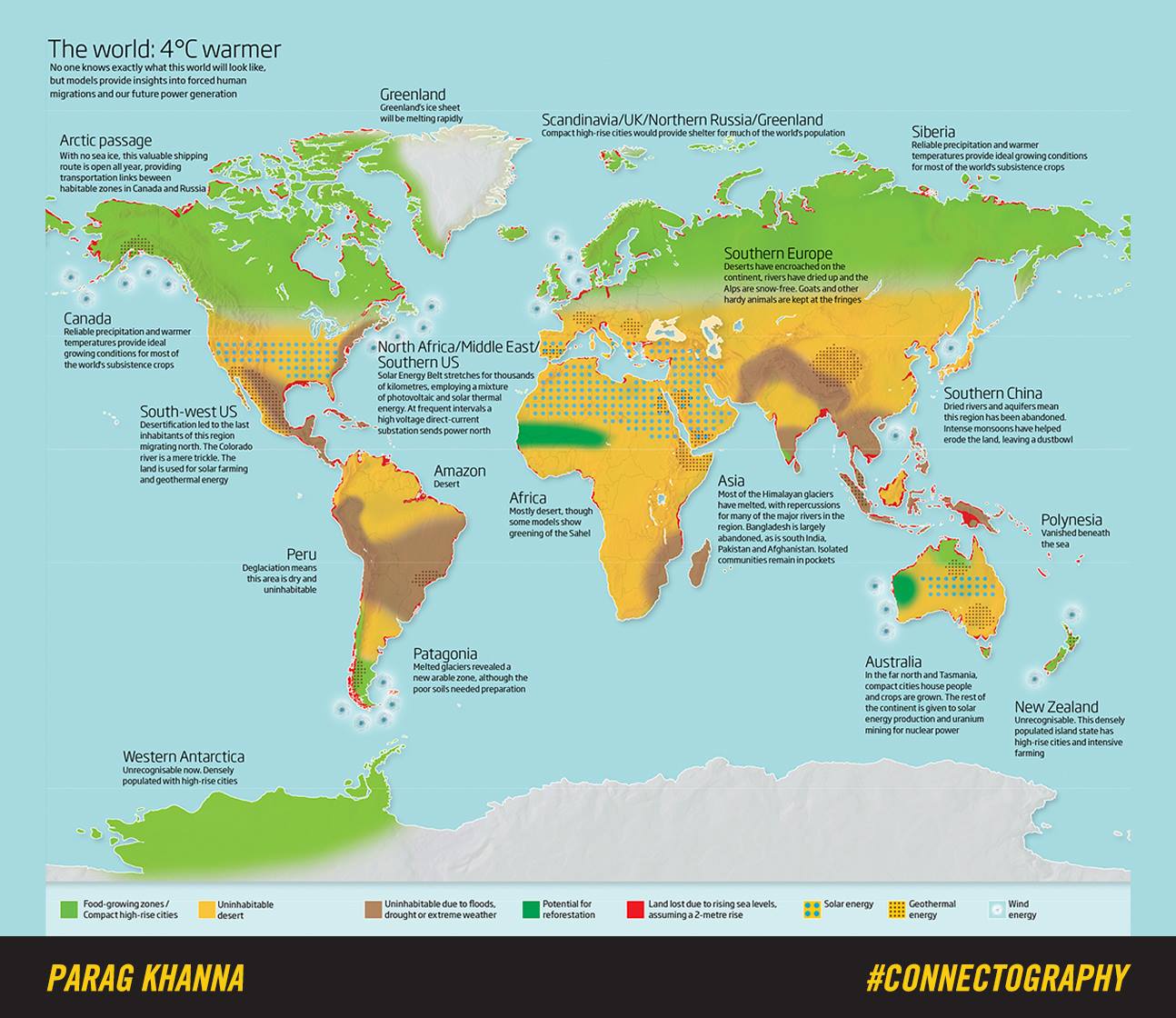

Humanity faces few larger questions than what, exactly, to do about climate change — and, in a sense larger still, what climate change even means. We’ve all heard a variety of different future scenarios laid out, each of them based on different data. But data can only make so much of an impact unless translated into a form with which the imagination can readily engage: a visual form, for instance, and few visual forms come more tried and true than the map.

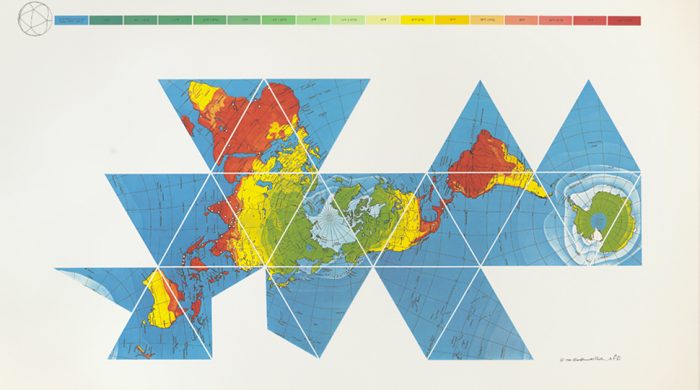

And so “leading global strategist, world traveler, and best-selling author” Parag Khanna has created the map you see above (view in a larger format here), which shows us the state of our world when it gets just four degrees celsius warmer. “Micronesia is gone – sunk beneath the waves,” writes Big Think’s Frank Jacobs in an examination of Khanna’s map. “Pakistan and South India have been abandoned. And Europe is slowly turning into a desert.”

But “there is also good news: Western Antarctica is no longer icy and uninhabitable. Smart cities thrive in newly green and pleasant lands. And Northern Canada, Scandinavia, and Siberia produce bountiful harvests to feed the hundreds of millions of climate refugees who now call those regions home.”

Not quite as apocalyptic a climate-change vision as some, to be sure, but it still offers plenty of considerations to trouble us. Lands in light green, according to the map’s color scheme, will remain or turn into “food-growing zones” and “compact high-rise cities.” Yellow indicates “uninhabitable desert,” brown areas “uninhabitable due to floods, drought, or extreme weather.” In dark green appear lands with “potential for reforestation,” and in red those places that rising sea levels have rendered utterly lost.

Those last include the edges of many countries in Asia (and all of Polynesia), as well as the area where the southeast of the United States meets the northeast of Mexico and the north and south coasts of South America. But if you’ve ever wanted to live in Antarctica, you won’t have to move into a research base: within a couple of decades, according to Khanna’s data, that most mysterious continent could become unrecognizable and “densely populated with high-rise cities,” presumably with their own hipster quarters. But where best to grow the ingredients for its avocado toast?

Anyone interested in Parag Khanna’s map will want to check out his book, Connectography: Mapping the Future of Global Civilization.

via Big Think

Related Content:

Global Warming: A Free Course from UChicago Explains Climate Change

A Century of Global Warming Visualized in a 35 Second Video

132 Years of Global Warming Visualized in 26 Dramatically Animated Seconds

A Song of Our Warming Planet: Cellist Turns 130 Years of Climate Change Data into Music

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

er

er