By reasons of parenting, I’ve become well acquainted with a song—perhaps you know it?— called “Fifty Nifty United States,” taught to schoolchildren as a geographical mnemonic device. The lyrics mention that “each individual state contributes a quality that is great.” What are some great qualities of, say, Delaware, New Mexico, or South Dakota? We aren’t told. Hey, it’s enough that a five or six-year-old can remember “shout ‘em, scout ‘em, tell all about ‘em” before rattling off an alphabetical list of “ev’ry state in the good old U.S.A.”

But if you hail from the U.S., you can enumerate many contributions from a few nifty states, whether culinary delights, historical events, writers, artists, sports heroes, etc. And most everyone’s got stories about visiting natural wonders, hiking mountain trails, fording rivers, gazing upon breathtaking vistas.

We may be occasional tourists, travel enthusiasts, or experts, but whatever our level of experience in the country, it’s probably kid stuff compared to the work of the scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

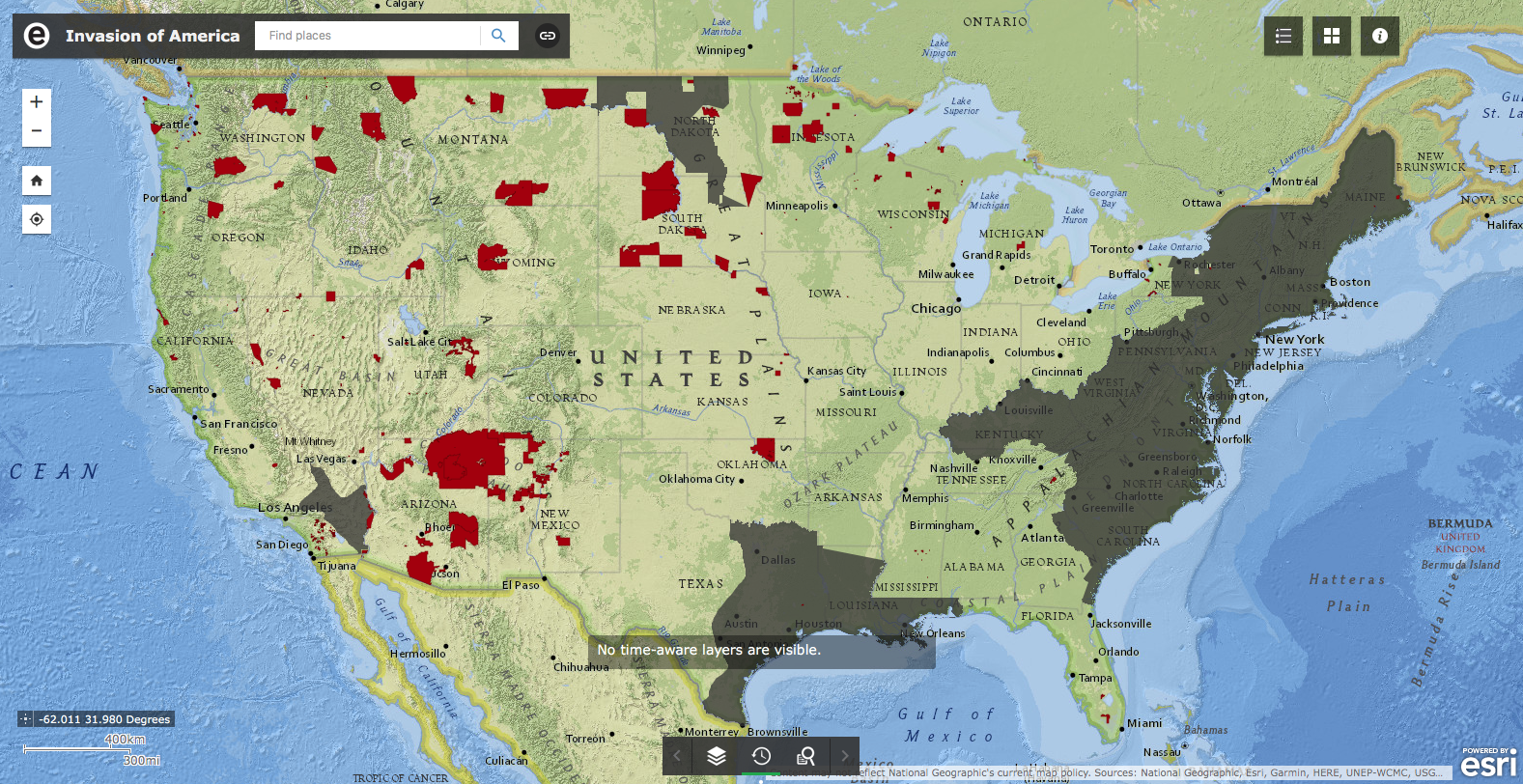

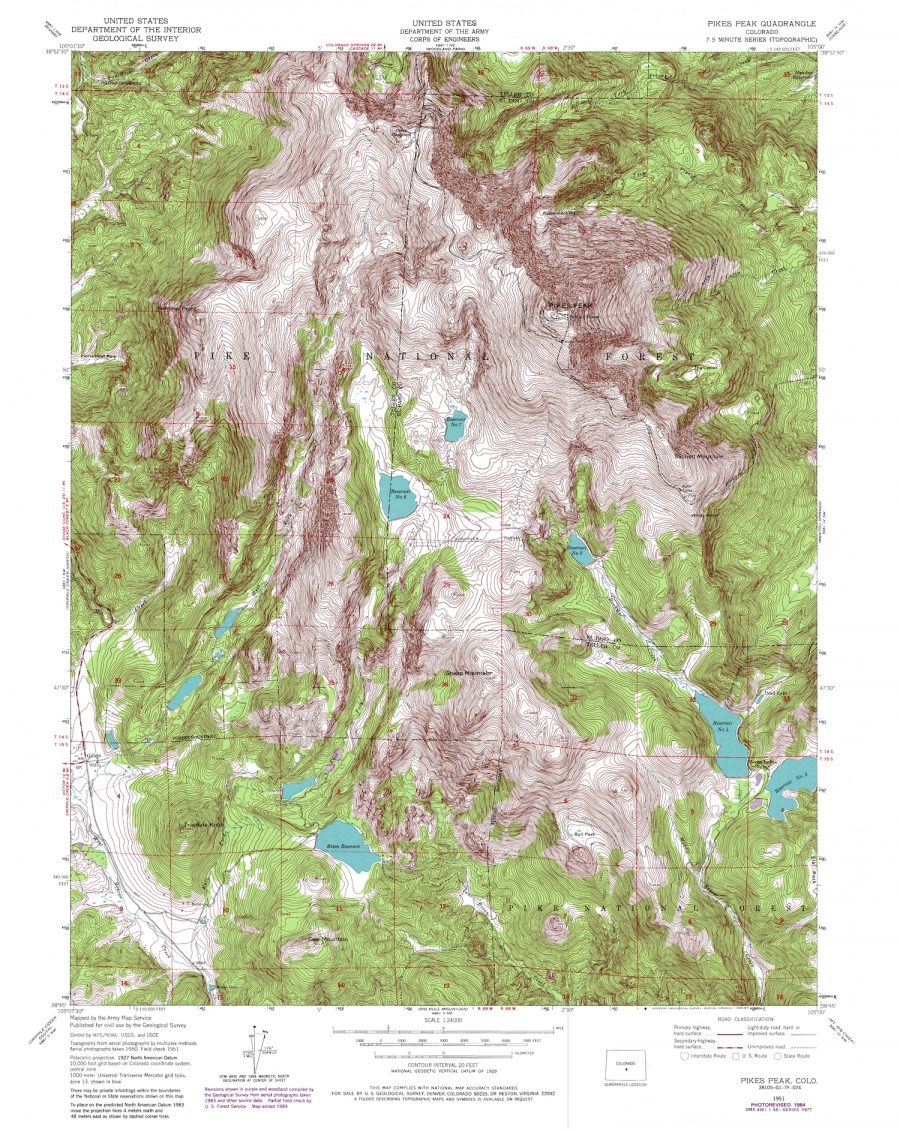

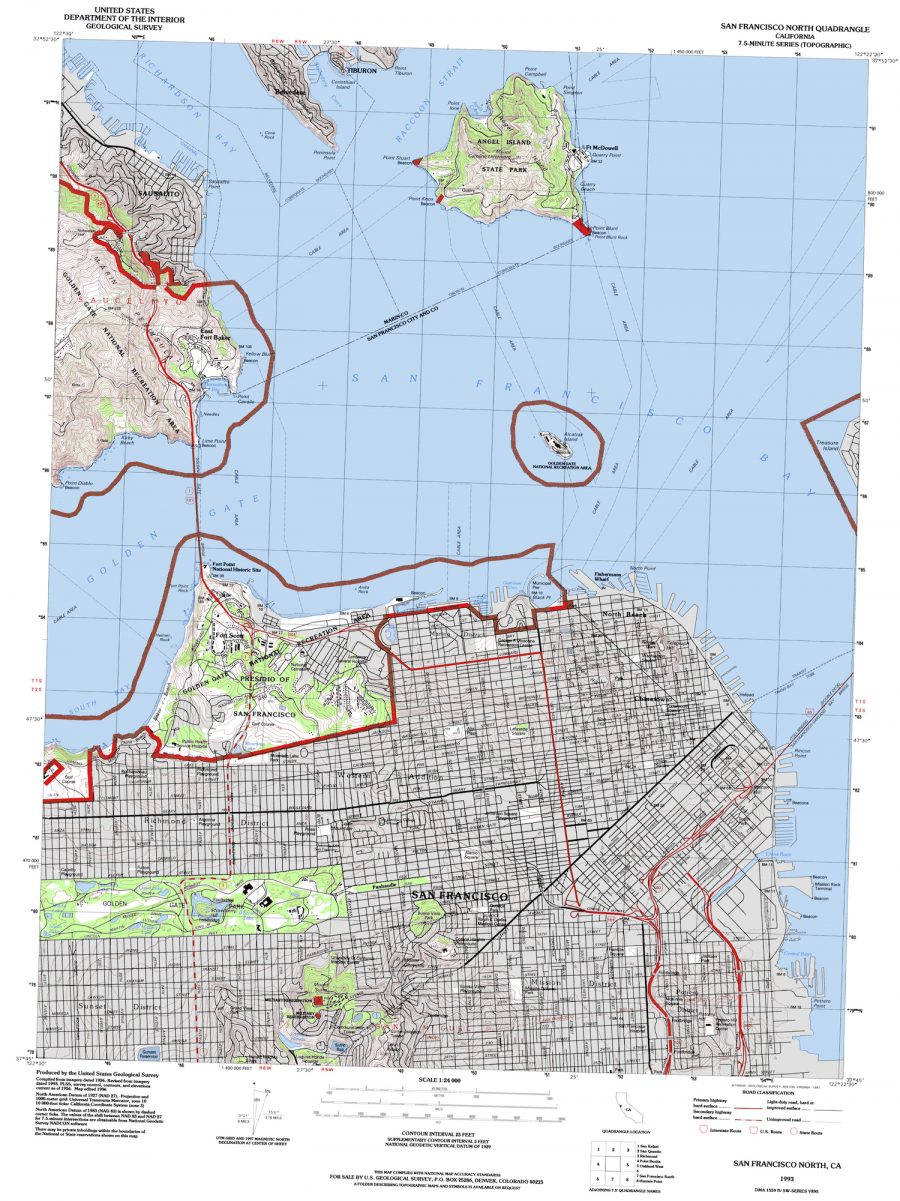

Established by Congress in 1879, this august body has documented U.S. lands and waters for 125 years, gathering an incredible amount of detailed information as “the nation’s largest water, earth, and biological science and civilian mapping agency.” Thanks to the Libre Map Project, the general public can view and download nearly 60,000 of those topographical maps, from all fifty states, and nearly every region within each of those states. See Colorado’s Pike National Forest and surrounding environs, at the top, for example, created from aerial photographs taken in 1950. Above, see a map of San Francisco, compiled in 1956, then revised in 1993 and further edited in 1996.

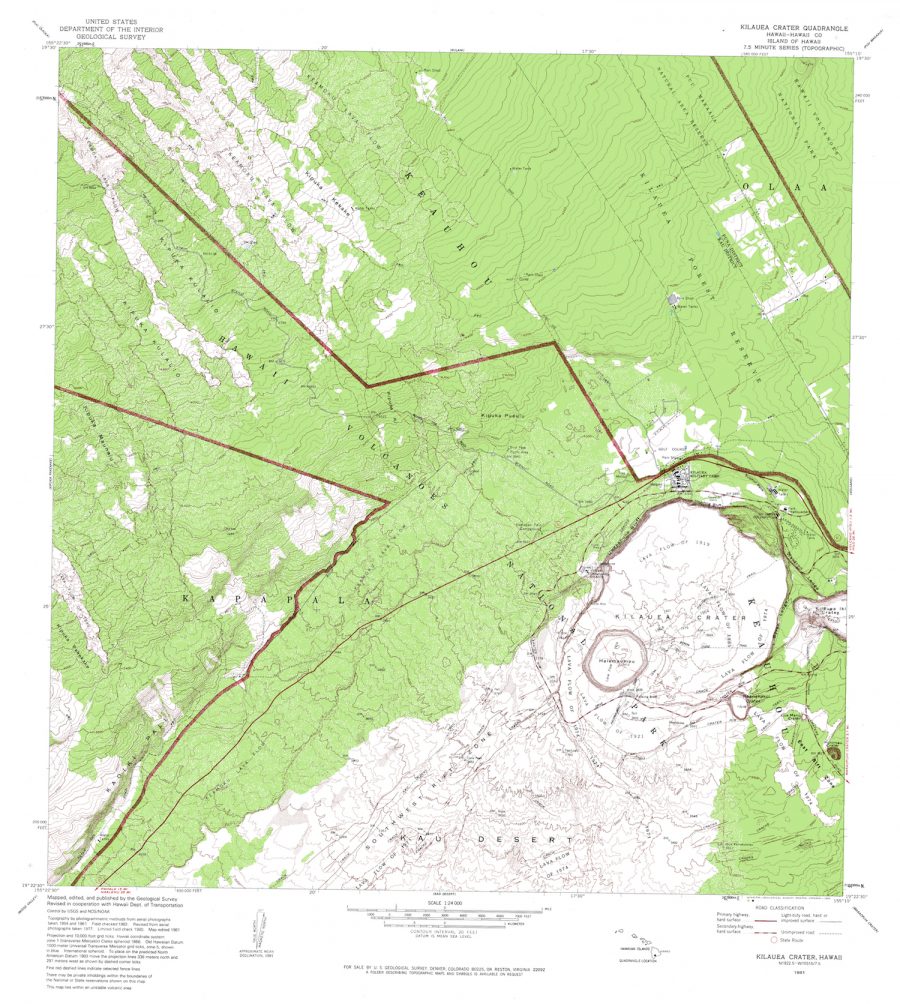

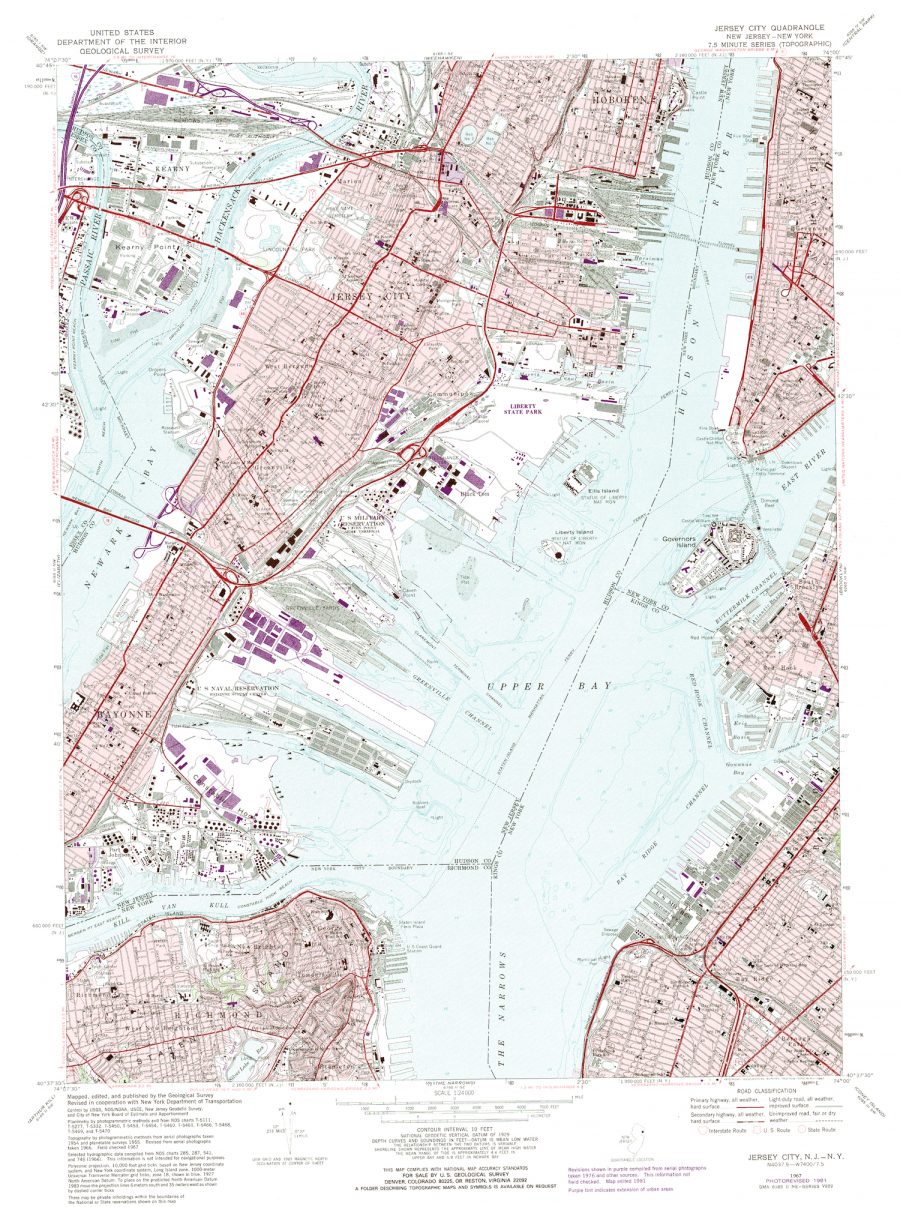

And just above, the devastating Kīlauea Volcano, in a map compiled from aerial photos taken in 1954 and 1961. (See the USGS site for the latest info about the ongoing eruption there.) Below, a nifty map of New York City, created “by photogrammetric methods from aerial photographs taken [in] 1954 and planetable surveys [in] 1955. Revised from aerial photographs taken [in] 1966.” Google maps may be more current, but these USGS maps have an aura of scientific authority around them, evidence of painstaking surveys, checked and rechecked over the decades by hundreds of pairs of hands and eyes.

Browsing the archive can be a challenge, since the maps are catalogued by coordinates rather than place names, but you can enter the names of specific locations in the search field. Also, be advised, the maps “are best used with global positioning software,” the archive tells visitors. Nonetheless, you can click on the first download option for “Multi Page Processed TIFF” to pull up a huge, downloadable image. Enter the archive here and get to scouting.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness