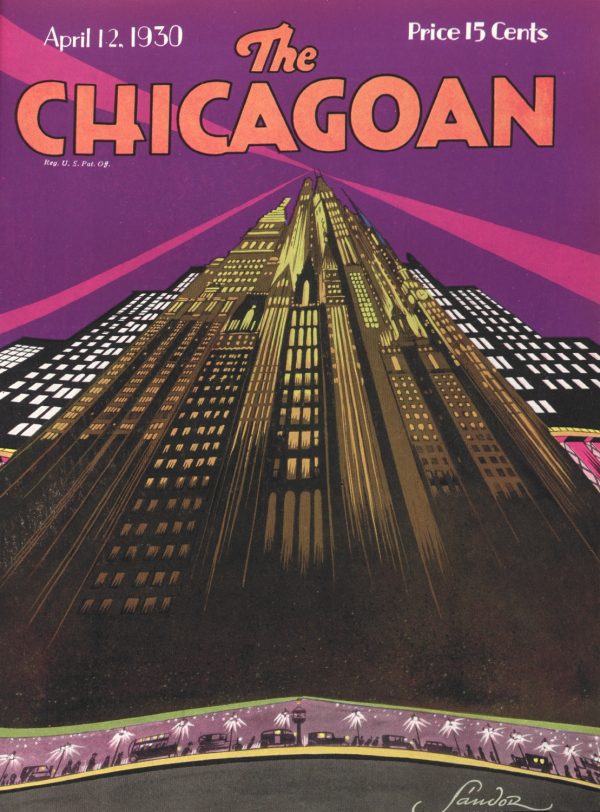

The early years of the Soviet Union roiled with internal tensions, intrigues, and ideological warfare, and the new empire’s art reflected its uneasy heterodoxy. Formalists, Futurists, Suprematists, Constructivists, and other schools mingled, published journals, critiqued and reviewed each other’s work, and like modernists elsewhere in the world, experimented with every possible medium, including those just coming into their own at the beginning of the 20th century, like film and photography.

These two mediums, along with radio, also happened to serve as the primary means of propagandizing Soviet citizens and carrying the messages of the Party in ways everyone could understand. And like much of the rest of the world, photography engendered its own consumer culture.

Out of these competing impulses came Soviet Photo (Sovetskoe foto), a monthly photography magazine featuring, writes Ksenia Nouril at the Museum of Modern Art’s site, “editorials, letters, articles, and photographic essays alongside advertisements for photography, photographic processes, and photographic chemicals and equipment.”

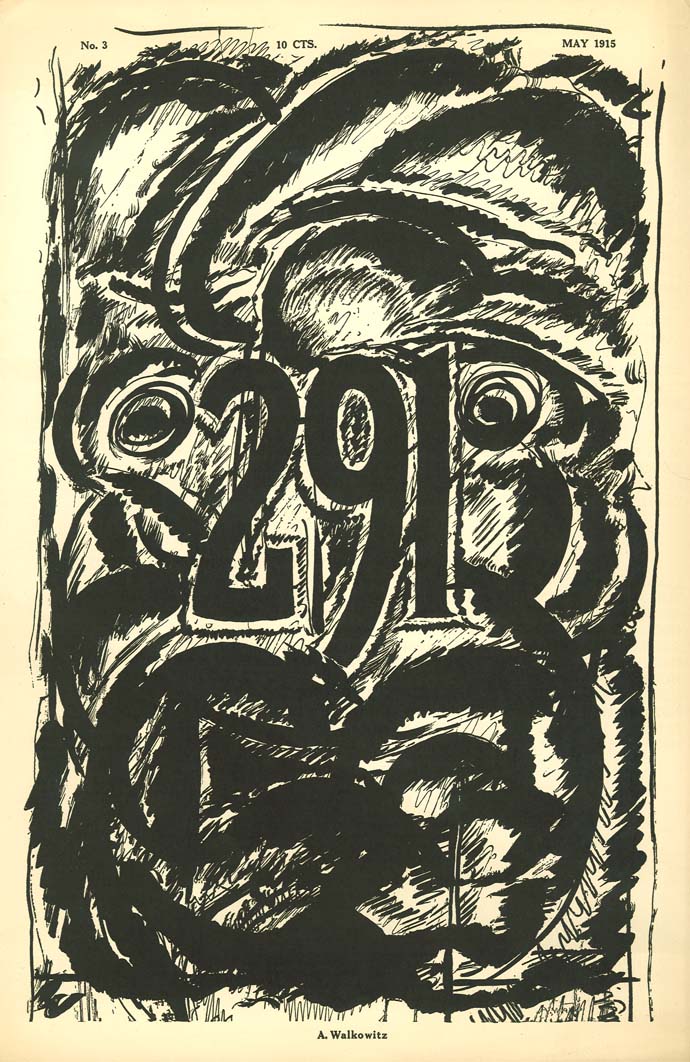

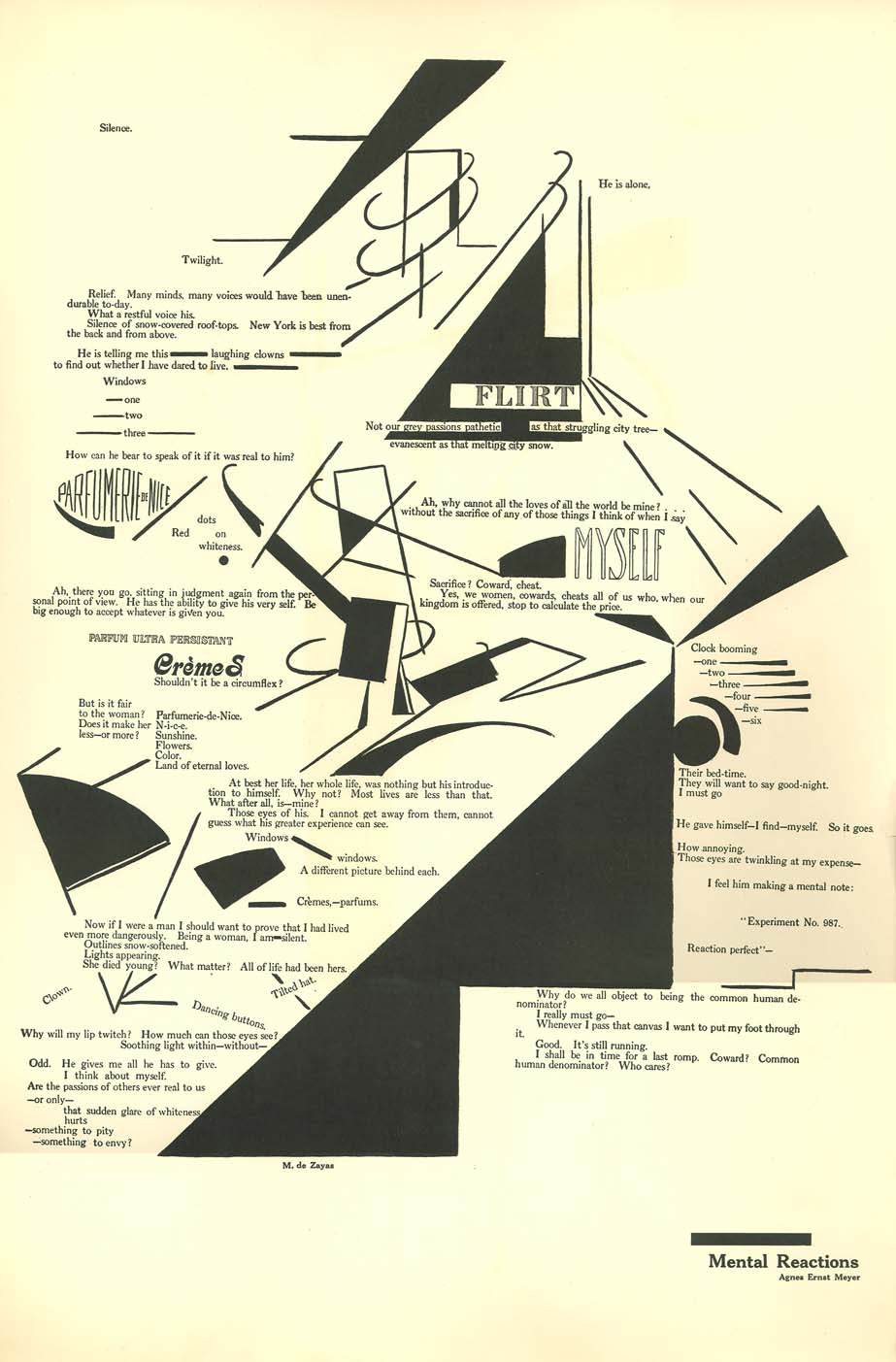

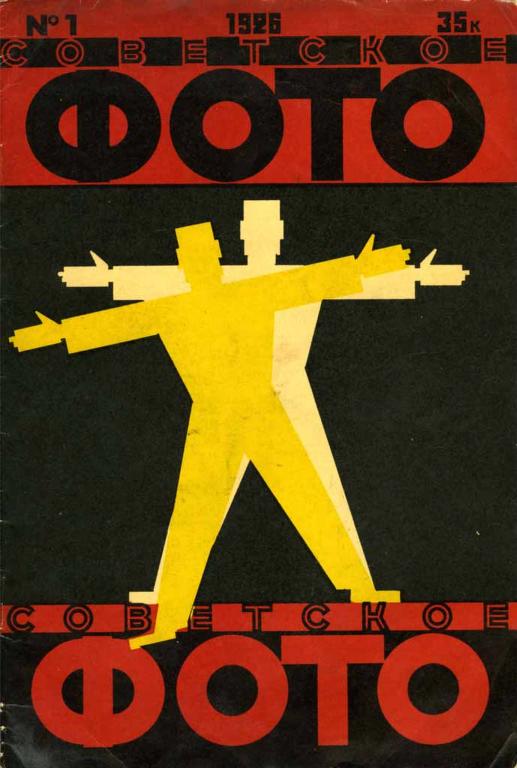

Soviet Photo was not founded by artists, but by a photojournalist, Arkady Shaikhet, in 1926 (see the first issue’s cover at the top). Though its audience primarily consisted of a “Soviet amateur photographers and photo clubs,” its early years freely mixed documentary, didacticism, and experimental art. It published the “works of international and professional photographers” and that of avant-gardists like Constructivist painter and graphic designer Aleksander Rodchenko.

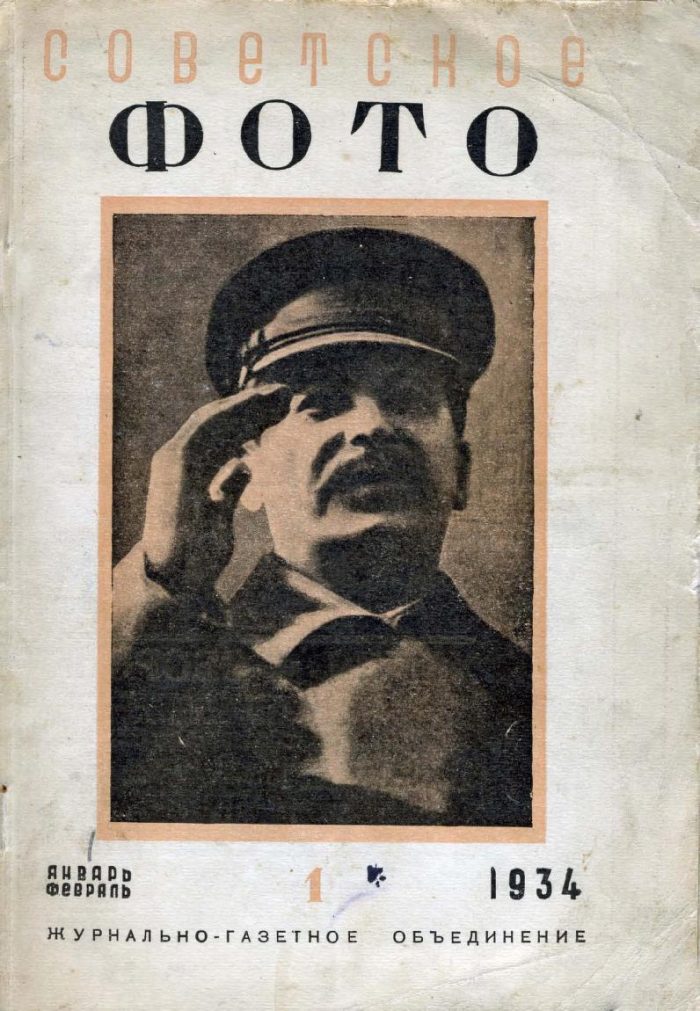

The aesthetic purges under Stalin—in which artists and writers one after another fell victim to charges of elitism and obscurantism—also played out in the pages of Soviet Photo. “Even before Socialist Realism was decreed to be the official style of the Soviet Union in 1934,” Nouril writes, “the works of avant-garde photographers,” including Rodchenko, “were denounced as formalist (implying that they reflected a foreign and elitist style).” Soviet Photo boycotted Rodchenko’s work in 1928 and “throughout the 1930s this state-sanctioned journal became increasingly conservative,” emphasizing “content over form.”

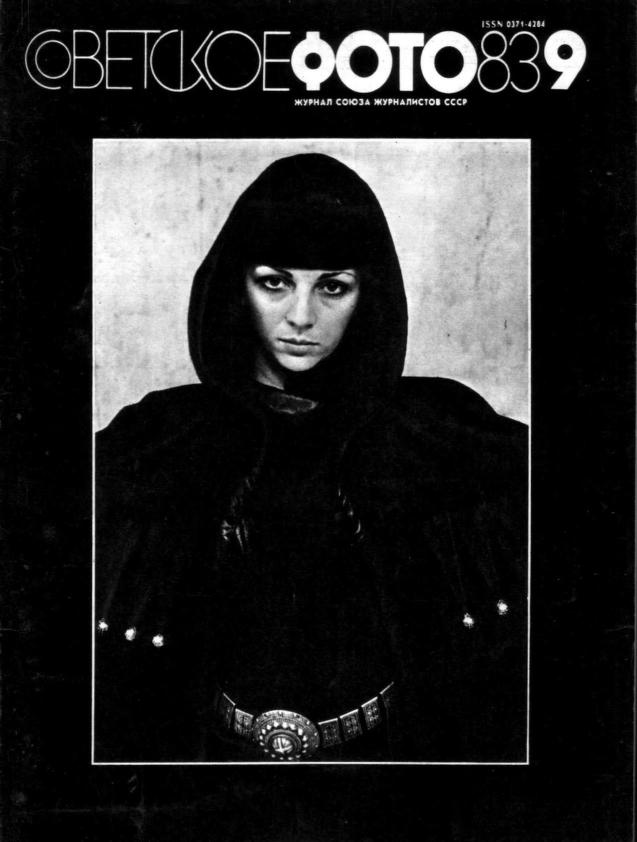

This does not mean that that the contents of the magazine were inelegant or pedestrian. Though it once briefly bore the name Proletarskoe foto (Proletariat Photography), and tended toward monumental and industrial subjects, war photography, and idealizations of Soviet life during the Stalinist years. After the 60s thaw, experimental photomontages returned, and more abstract compositions became commonplace. Soviet Photo also kept pace with many glossy magazines in the West, with stunning full-color photojournalism and, after glasnost and the fall of the Berlin wall, high fashion and advertising photography.

Fans of photography, Soviet history, or some measure of both, can follow Soviet Photo’s evolution in a huge archive featuring 437 digitized issues, published between 1926 and 1991. Expect to find a gap between 1942 and 1956, when publication ceased “due to World War II and the war’s aftereffects.” Aside from these years and a few other missing months, the archive contains nearly every issue of Soviet Photo, free to browse or download in various formats. “Dig deep enough,” writes photo blog PetaPixel, “and you’ll find some really interesting (and surprisingly familiar) things in there.” Enter the archive here.

via PetaPixel

Related Content:

Behold a Beautiful Archive of 10,000 Vintage Cameras at Collection Appareils

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness