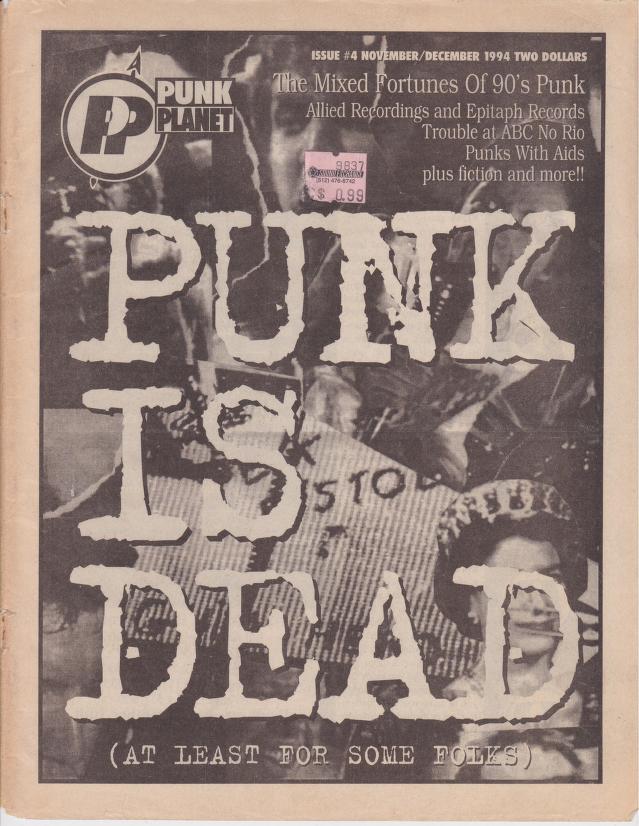

Punk didn’t die, it evolved, since its inception in the 70s to the ethos of majorly influential figures like Kathleen Hanna and Ian MacKaye in the 90s, two of the most prominent faces of progressive DIY punk in the U.S. Then, as before, scenes came together around zines, sites of cultural recognition, dissemination, and recording for posterity in the archives of physical print. One zine critical to the socially conscious punk that emerged at the time, Punk Planet, has recently been digitized in all 80 issues by the Internet Archive.

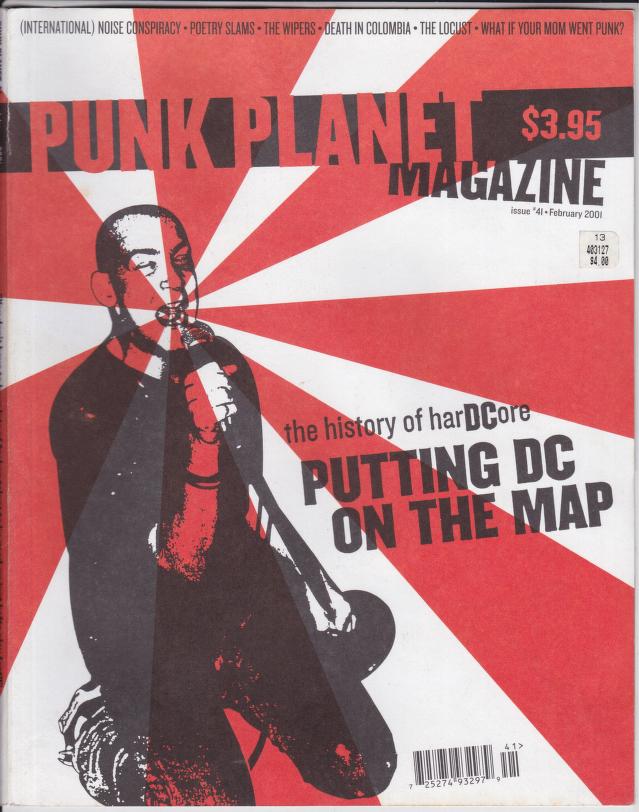

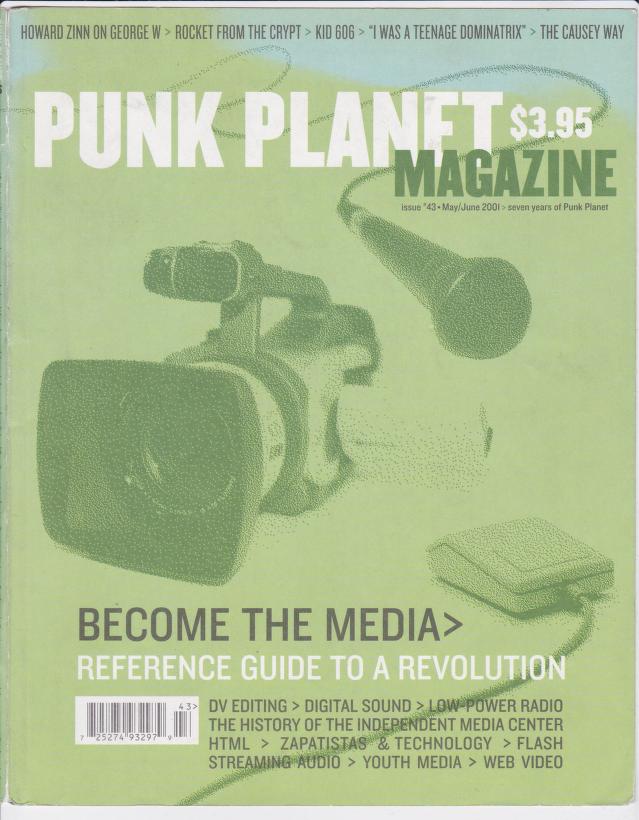

Based in Chicago and founded by editor Dan Sinker (whom you may know from his presence on Twitter), Punk Planet ran from 1994 to 2007, focusing “most of its energy on looking at punk subculture,” the Internet Archive writes, “rather than punk as simply another genre of music to which teenagers listen. In addition to covering music, Punk Planet also covered visual arts and a wide variety of progressive issues—including media criticism, feminism, and labor issues.”

Punk Planet “transcended stereotypes to chronicle the progressive underground community, from thoughtful band interviews to exceptionally thorough investigative features,” wrote the A.V. Club’s Kyle Ryan in an interview with Sinker the year of the magazine’s demise.

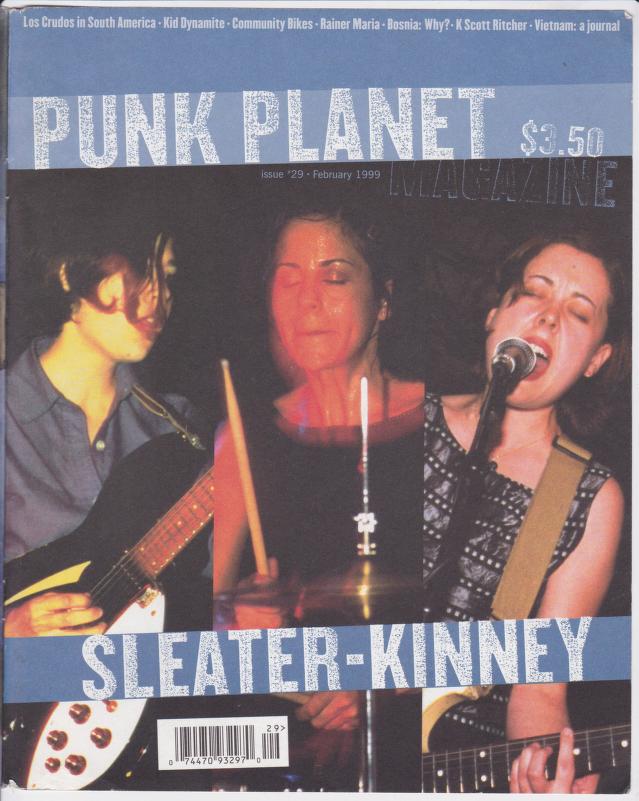

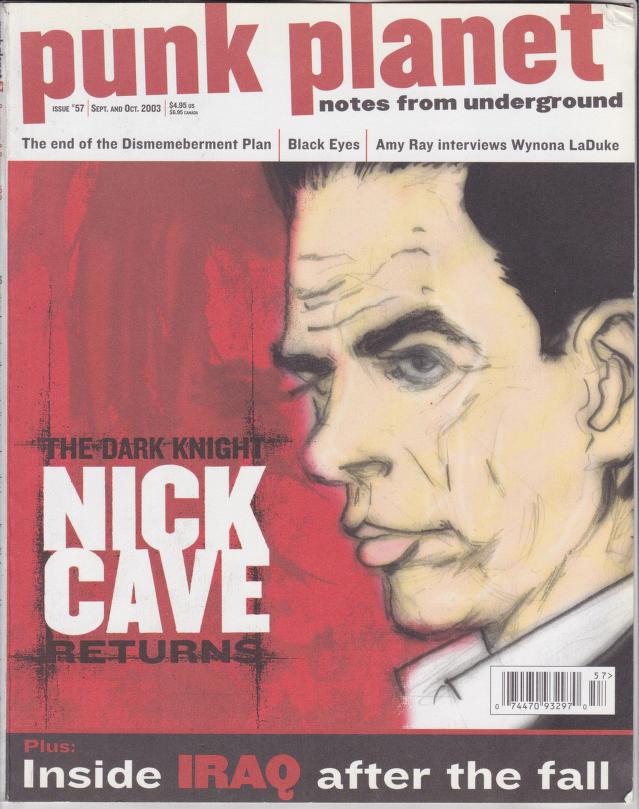

“Over the course of 13 years, Punk Planet became heavily influential beyond the increasingly small world of independent publishing.” Arguably, that influence can be felt in online magazines like Rookie as well as music-focused stalwarts like Pitchfork, who note that Punk Planet’s “issues included interviews with Sleater-Kinney, Nick Cave, Ralph Nader, and countless other cultural icons.”

The magazine folded for the usual reasons, as Utne noted in a farewell, leaving a “gaping hole in the landscape of independent magazines…. The deck was stacked against Punk Planet, though, and the hard knocks of independent publishing finally became too much to bear.” Sinker says he saw the end as part of a bigger picture and “started looking at the larger issues that were also affecting us. Things like, ‘Hey, wow, record labels are going under because no one is paying for music!’ And, ‘Hey, look at this, people are going to these Internet sites because people can pick up a record review the same day the record came out!’”

It’s a moot point now—2020 has not made it any easier for small publications and independent musicians to survive. But the continued existence of Punk Planet online for new generations to discover promises to foster the continuity that carried the spirit of punk rock through decades of evolutionary change. Enter the Punk Planet archive here.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness