Having once been involved in the founding of an arts magazine, I have experienced intimately the ways in which such an endeavor can depend upon a community of equals pooling a diversity of skills. The process can be painful: egos compete, certain elements seek to dominate, but the successful product of such a collaborative effort will represent a living community of artists, writers, editors, and other masters of technique who subordinate their individual wills, temporarily, to the will of a collective, creating new gestalt identities from conceptual atoms. As Monoskop—“a wiki for collaborative studies of art, media and the humanities”—points out, “the whole” of an arts magazine, “could become greater than the sum of its parts.” Often when this happens, a publication can serve as the platform or nucleus of an entirely new movement.

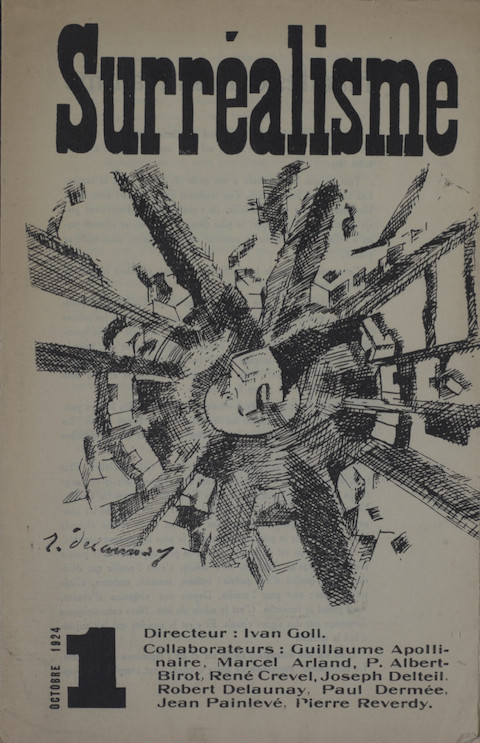

Monoskop maintains a digital archive of printed avant-garde and modernist magazines dating from the late-19th century to the late 1930s, published in locales from Arad to Bucharest, Copenhagen to Warsaw, in addition to the expected New York and Paris. From the latter city comes the 1924 first issue of Surrealisme at the top of the post.

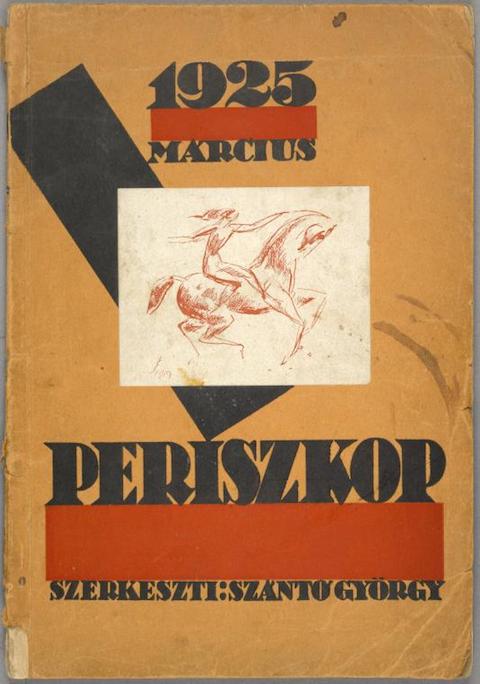

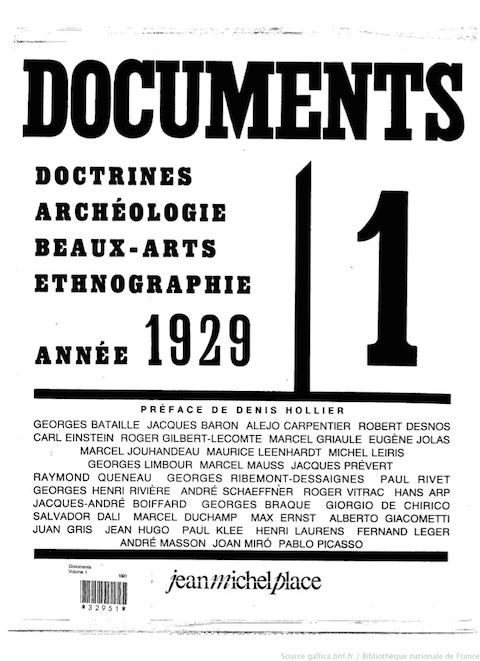

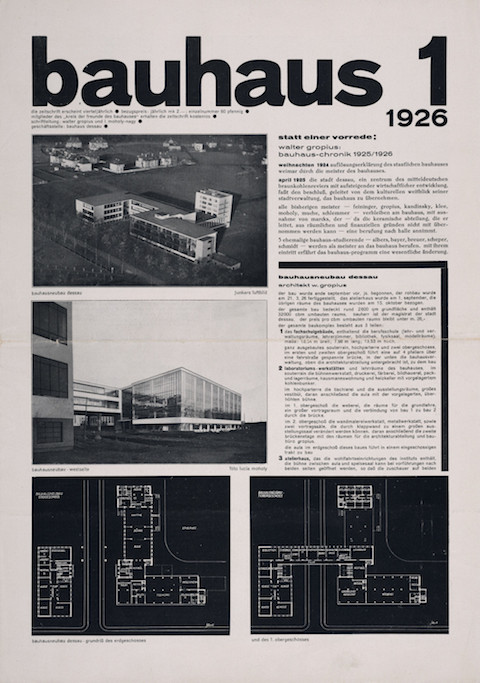

From the much smaller city of Arad in Romania comes the March, 1925 issue 1 of Periszkóp above, published in Hungarian and featuring works by Picasso, Marc Chagall, and many lesser-known Eastern European artists. Just below, see another Paris publication: the first, 1929 issue of Documents, a surrealist journal edited by Georges Bataille and featuring such luminaries as Cuban novelist Alejo Carpentier and artists Georges Braque, Giorgio De Chirico, Salvador Dali, Marcel Duchamp, Paul Klee, Joan Miro, and Pablo Picasso. Further down, see the first, 1926, issue of the Bauhaus journal, vehicle of the famous arts movement founded by Walter Gropius in 1919.

The variety of modernist and avant garde publications archived at Monoskop “provide us with a historical record of several generations of artists and writers.” They also “remind us that our lenses matter.” In an age of “the relentless linearity of digital bits and the UX of the glowing screen” we tend to lose sight of such critically important matters as design, typography, layout, writing, and the “techniques of printing and mechanical reproduction.” Anyone can build a website, fill it with “content,” and propagate it globally, giving little or no thought to aesthetic choices and editorial framing. But the magazines represented in Monoskop’s archive are specialized creations, the products of very deliberate choices made by groups of highly skilled individuals with very specific aesthetic agendas.

A majority of the publications represented come from the explosive period of modernist experimentation between the wars, but several, like the journal Rhythm: Art Music Literature—first published in 1911—offer glimpses of the early stirrings of modernist innovation in the Anglophone world. Others like the 1890–93 Parisian Entretiens politiques et littéraires showcase the work of pioneering early French modernist forebears like Jules Laforgue (a great influence upon T.S. Eliot) and also André Gide and Stéphane Mallarmé. Some of the publications here are already famous, like The Little Review, many much lesser-known. Most published only a handful of issues.

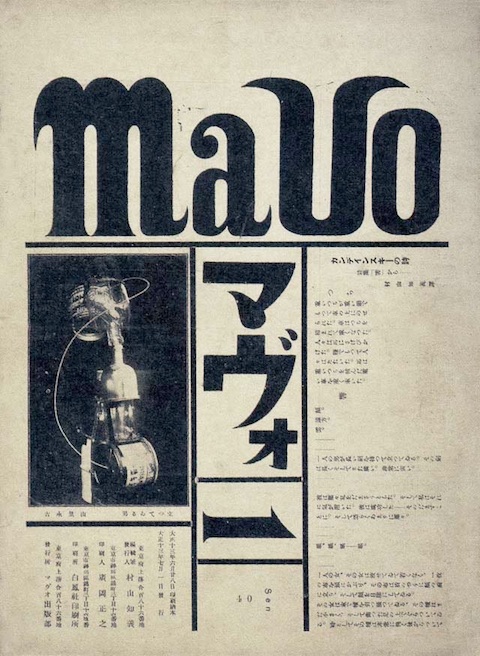

With a few exceptions—such as the 1923 Japanese publication MAVO shown above—almost all of the journals represented at Monoskop’s archive hail from Eastern and Western Europe and the U.S.. While “only a few journals had any significant impact outside the avant-garde circles in their time,” the ripples of that impact have spread outward to encompass the art and design worlds that surround us today. These examples of the literary and design culture of early 20th century modernist magazines, like those of late 20th century postmodern ‘zines, provide us with a distillation of minor movements that came to have major significance in decades hence.

Related Content:

The ABCs of Dada Explains the Anarchic, Irrational “Anti-Art” Movement of Dadaism

William S. Burrough’s Avant-Garde Movie ‘The Cut Ups’ (1966)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness