If you’re thirsty, a vending machine is usually close by. (Especially if you’re in Japan. You’re probably standing right next to one right now!) But what if you have time to kill and you’re thirsty for literature? Then the Short Édition vending machine might be for you. Choose one of three buttons—one minutes, three minutes, or five minutes—and the cylindrical machine, currently available in France, will print out an appropriately-long short story to read on a receipt-like piece of paper.

Short Édition co-founder Quentin Pleple says the idea came to him, where else, at a vending machine, while on break with co-workers.“We thought it would be cool to have it for short stories. Then, a couple of days later we decided to hack a prototype.”

Though people spend a lot of their free time on their pocket devices, the Short Édition is another attempt–like the short stories Chipotle printed on the side of its drinking cups–to free us from a life of staring at glowing rectangles. It’s tangible yet disposable at the same time.

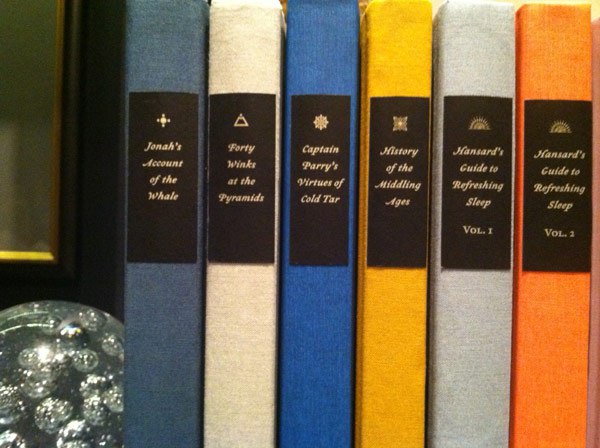

At the turn of the 20th century automation and vending machines looked to be the wave of the future, where everything would be done for us on command. And that has happened in a totally different way, through the microprocessor. It just didn’t happen through the vending machine, at least not in America, where they mostly dispense food, drink, and cigarettes. Like high speed rail, Japan has picked up the slack and made the world rethink the machine’s possibilities all over again. It now looks like France and Poland (where you can find Haruki Murakami novels being sold in vending machines) are catching on.

The Short Édition vending machines, currently only available in eight locations in Grenoble, France, draw from a database of 600 stories chosen by the community at Short Édition’s website, which counts 1,100 authors as members. Presumably, all these stories are in French.

While new, the machines have gathered enough media attention to attract inquiries from Italy and the United States. So look out, you might find one in your area soon.

Related Content:

Haruki Murakami Novels Sold in Polish Vending Machines

Isaac Asimov Predicts in 1964 What the World Will Look Like Today

Kurt Vonnegut’s 8 Tips on How to Write a Good Short Story

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the FunkZone Podcast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.