An interesting thing happens when you read certain of George Saunders’ stories. At first, you see the satirist at work, skewering American meanness and banality with the same unsparing knife’s edge as earlier postmodernists like John Barth or Donald Barthelme. Then you begin to notice something else taking shape… something perhaps unexpected: compassion. Rather than serving as paper targets of Saunders’ dark humor, his misguided characters come to seem like real people, people he cares about; and the real target of his satire becomes a culture that alienates and devalues those people.

Take the oft-anthologized “Sea Oak,” a farcical melodrama about a dead aunt who returns reanimated to annoy and depress her downwardly mobile family members. The stage is set for a series of buffoonish episodes that, in the hands of a less mature writer, might play out to emphasize just how ridiculous these characters’ lives are, and how justifiably we—author and reader—might mock them from our perches. Saunders does not do this at all. Rather than distancing, he draws us closer, so that the characters in the story become more sympathetic and three-dimensional even as events become increasingly outlandish.

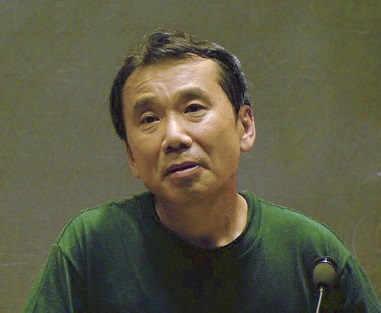

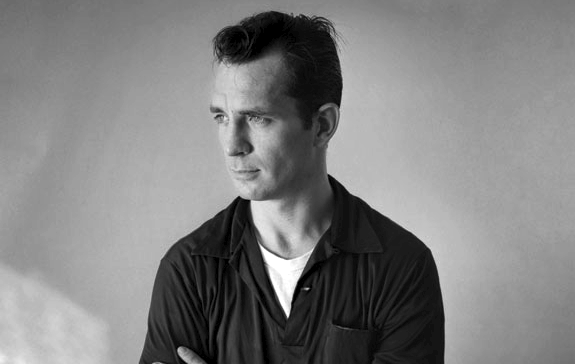

All of this humanizing is by design, or rather, we might say that empathy is baked into Saunders’ ethos—one he has articulated many times in essays, interviews, and a moving 2013 Syracuse University commencement speech. Now we can see him in a candid filmed appearance above, in a documentary titled “George Saunders: On Story” by Redglass Pictures (executive produced by Ken Burns). Created from a two-hour interview with Saunders, the short video at the top offers “a direct look at the process by which he is able to take a single mundane sentence and infuse it with the distinct blend of depth, compassion, and outright magic that are the trademarks of his most powerful work.”

In Saunders’ own words, “a good story is one that says, at many different levels, ‘we’re both human beings, we’re in this crazy situation called life, that we don’t really understand. Can we put our heads together and confer about it a little bit at a very high, non-bullshitty level?’ Then, all kinds of magic can happen.” The rest of Saunders’ fascinating monologue on story gets an animated treatment that illustrates the magic he describes. If you haven’t read Saunders, this is almost as good an introduction to him as, say, “Sea Oak.” His thoughts on the role fiction plays in our lives and the ways good stories work are always lucid, his examples vividly inventive. The effect of listening to him mirrors that of sitting in a seminar with one of the best teachers of creative writing, which Saunders happens to be as well.

I would love to take a class with him, but barring that, I’m very happy for the chance to hear him discuss writing techniques and philosophy in the short film at the top and in the interview extras below it: “On the relationship between reader and writer,” “On the tricks of the writing process,” and “In defense of darkness.” Praised by no less a postmodernist luminary than Thomas Pynchon, Saunders’ story collections like CivilWArLand in Bad Decline, Pastoralia, and In Persuasion Nation get at much of what ails us in these United States, but they do so always with an underlying hopefulness and a “non-bullshitty” conviction of shared humanity.

You can read 10 of Saunders’ stories free—including “Sea Oak” and the excellent “The Red Bow”—here.

Related Content:

The Importance of Kindness: An Animation of George Saunders’ Touching Graduation Speech

Kurt Vonnegut’s 8 Tips on How to Write a Good Short Story

Ray Bradbury Gives 12 Pieces of Writing Advice to Young Authors (2001)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness