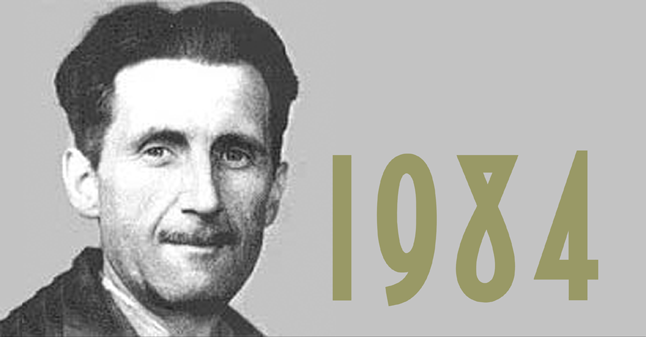

Image via Wikimedia Commons

In 1983, Anthony Burgess took up a commission from a Nigerian publishing company and, in two weeks, delivered to them the manuscript for Ninety-Nine Novels: The Best in English since 1939 — A Personal Choice. Published the following year, the book delivers exactly what its title, subtitle, and sub-subtitle promises: the finest novels English-language writers produced between the years 1939 and 1983, according to the preferences of the writer of more than a few novels himself, including A Clockwork Orange, Earthly Powers, and 1985.

Burgess wrote that last one, so its own title may suggest, as a tribute to George Orwell’s 1984, one of those 99 novels. “Nineteen eighty four has arrived, but George Orwell’s glum prophecy has not been fulfilled,” Burgess declared in a New York Times piece published as that year began. Yet “for 35 years a mere novel, an artifact meant primarily for diversion, has been scaring the pants off us all. Evidently the novel is a powerful literary form which is capable of reaching out into the real world and modifying it. It is a form which even the nonliterary had better take seriously.”

Prolific in his literary consumption as well as production, Burgess got plenty of practice taking the novel seriously in his capacity as a book reviewer. “It was clear that certain novels had to be reviewed whether I wished to review them or not,” he writes. “A new Graham Greene or Evelyn Waugh — this was the known brand-name which would grant an expected satisfaction. But the unknown had to be considered as well. After all, both Greene and Waugh produced first novels. V. S. Naipaul’s first novel went totally unreviewed.” Greene appears among the 99 for The Power and the Glory and The Heart of the Matter, Waugh for Brideshead Revisited and Sword of Honor, and Naipaul for A Bend in the River.

What makes these novels, and Burgess’ other 93 picks, so good? “The primary substance I have considered in making my selection is human character,” meaning that their authors have created “human beings whom we accept as living creatures filled with complexities and armed with free will” — and who thus, to a great extent, shape the story independently of authorial intention. “At best there will be a compromise between the narrative line you have dreamed up and the course of action preferred by the characters,” writes Burgess, as if addressing his colleagues in the enterprise of presenting “the preoccupations of real human beings through invented ones.”

You can see Burgess’ full list of 99 novels below, which includes such other favorite writers here at Open Culture as J.G. Ballard, Aldous Huxley (who scores three hits), James Joyce, and Vladimir Nabokov, all of whom, beyond their duty to character, “have managed language well, have clarified the motivations of action, and have sometimes expanded the bounds of imagination. And they entertain or divert, which means to turn our faces away from the repetitive patterns of daily life and look at humanity and the world with a new interest and even joy.” Only one question remains: why exactly 99? “The reader can decide on his own 100th,” Burgess replies. “He may even choose one of my own novels.”

Note: you can purchase online used copies of Ninety-Nine Novels: The Best in English since 1939 — A Personal Choice. It runs about 160 pages. Now here’s the basic list.

Achebe, Chinua — A Man of the People — (1966)

Aldiss, Brian — Life in the West (1980)

Amis, Kingsley — Lucky Jim (1954)

Amis, Kingsley — The Anti-Death League (1966)

Baldwin, James — Another Country (1962)

Ballard, J.G. — The Unlimited Dream Company (1979)

Barth, John — Giles Goat-Boy (1966)

Bellow, Saul — The Victim (1947)

Bellow, Saul — Humboldt’s Gift (1975)

Bowen, Elizabeth — The Heat of the Day (1949)

Bradbury, Malcolm — The History Man (1975)

Braine, John — Room at the Top (1957)

Cary, Joyce — The Horse’s Mouth (1944)

Chandler, Raymond — The Long Goodbye (1953)

Compton-Burnett, Ivy — The Mighty and Their Fall (1961)

Cooper, William — Scenes from Provincial Life (1950)

Davies, Robertson — The Rebel Angels (1982)

Deighton, Len — Bomber (1970)

Durrell, Lawrence — The Alexandria Quartet (1957)

Ellison, Ralph — Invisible Man (1952)

Faulkner, William — The Mansion (1959)

Fleming, Ian — Goldfinger (1959)

Fowles, John — The French Lieutenant’s Woman (1969)

Frayn, Michael — Sweet Dreams (1973)

Golding, William — The Spire (1964)

Gordimer, Nadine — The Late Bourgeois World (1966)

Gray, Alasdair — Lanark (1981)

Green, Henry — Party Going (1939)

Greene, Graham — The Power and the Glory (1940)

Greene, Graham — The Heart of the Matter (1948)

Harris, Wilson — Heartland (1964)

Hartley, L.P. — Facial Justice (1960)

Heller, Joseph — Catch-22 (1961)

Hemingway, Ernest — For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940)

Hemingway, Ernest — Old Man and the Sea (1952)

Hoban, Russell — Riddley Walker (1980)

Hughes, Richard — The Fox in the Attic (1961)

Huxley, Aldous — After Many a Summer (1939)

Huxley, Aldous — Ape and Essence (1948)

Huxley, Aldous — Island (1962)

Isherwood, Christopher — A Single Man (1964)

Johnson, Pamela Hansford — An Error of Judgement (1962)

Jong, Erica — How to Save Your Own Life (1977)

Joyce, James — Finnegans Wake (1939)

Lessing, Doris — The Golden Notebook (1962)

Lodge, David — How Far Can You Go? (1980)

Lowry, Malcolm — Under the Volcano (1947)

MacInnes, Colin — The London Novels (1957)

Mailer, Norman — The Naked and the Dead (1948)

Mailer, Norman — Ancient Evenings (1983)

Malamud, Bernard - The Assistant (1957)

Malamud, Bernard — Dubin’s Lives (1979)

Manning, Olivia — The Balkans Trilogy (1960)

Maugham, Somerset — The Razor’s Edge (1944)

McCarthy, Mary — The Groves of Academe (1952)

Moore, Brian — The Doctor’s Wife (1976)

Murdoch, Iris — The Bell (1958)

Nabokov, Vladimir — Pale Fire (1962)

Nabokov, Vladimir — The Defence (1964)

Naipaul, V.S. — A Bend in the River (1979)

Narayan, R.K. — The Vendor of Sweets (1967)

Nye, Robert — Falstaff (1976)

O’Brien, Flann — At Swim-Two-Birds (1939)

O’Connor, Flannery — Wise Blood (1952)

O’Hara, John — The Lockwood Concern (1965)

Orwell, George — Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949)

Peake, Mervyn — Titus Groan (1946)

Percy, Walker — The Last Gentleman (1966)

Plunkett, James — Farewell Companions (1977)

Powell, Anthony — A Dance to the Music of Time (1951)

Priestley, J.B. — The Image Men (1968)

Pynchon, Thomas — Gravity’s Rainbow (1973)

Richler, Mordecai — Cocksure (1968)

Roberts, Keith — Pavane (1968)

Roth, Phillip — Portnoy’s Complaint (1969)

Salinger, J.D. — The Catcher in the Rye (1951)

Sansom, William — The Body (1949)

Schulberg, Budd — The Disenchanted (1950)

Scott, Paul — Staying On (1977)

Shute, Nevil — No Highway (1948)

Sillitoe, Alan — Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1958)

Snow, C.P. - Strangers and Brothers (1940)

Spark, Muriel — The Girls of Slender Means (1963)

Spark, Muriel — The Mandelbaum Gate (1965)

Styron, William — Sophie’s Choice (1979)

Theroux, Alexander — Darconville’s Cat (1981)

Theroux, Paul — The Mosquito Coast (1981)

Toole, John Kennedy — A Confederacy of Dunces (1980)

Updike, John — The Coup (1978)

Vidal, Gore — Creation (1981)

Warner, Rex — The Aerodrome (1941)

Waugh, Evelyn — Brideshead Revisited (1945)

Waugh, Evelyn — Sword of Honor (1952)

White, T.H. — The Once and Future King (1958)

White, Patrick — Riders in the Chariot (1961)

Williamson, Henry — A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight (1951)

Wilson, Angus — The Old Men at the Zoo (1961)

Wilson, Angus — Late Call (1964)

Wouk, Herman — The Caine Mutiny (1951)

Related Content:

A Clockwork Orange Author Anthony Burgess Lists His Five Favorite Dystopian Novels: Orwell’s 1984, Huxley’s Island & More

Anthony Burgess’ Lost Introduction to Joyce’s Dubliners Now Online

Vladimir Nabokov Names the Greatest (and Most Overrated) Novels of the 20th Century

The 100 Best Novels: A Literary Critic Creates a List in 1898

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.