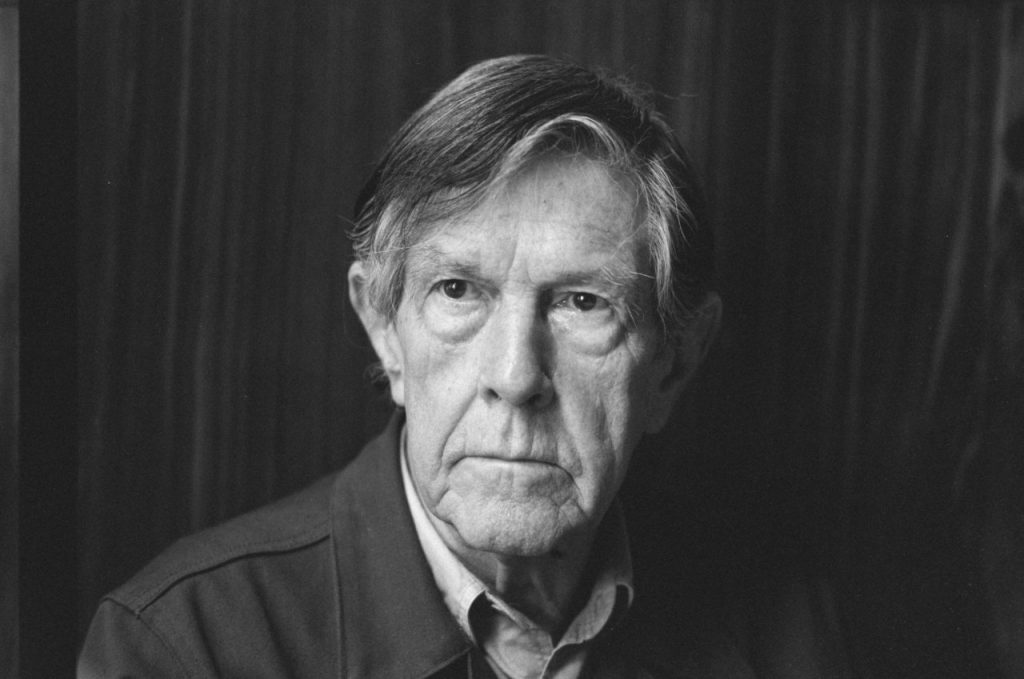

Image by United Press International, via Wikimedia Commons

When totalitarian regimes around the world are in power, writing that tells the truth—whether literary, journalistic, scientific, or legal—effectively serves as counter-propaganda. To write honestly is to expose: to uncover what is hidden, stand apart from it, and observe. These actions are anathema to dictatorships. But they are integral to resistance movements, which must develop their own press in order to disseminate ideas other than official state dogma.

For the French Resistance during World War II, one such publication that served the purpose came from a cell called “Combat,” which gave its name to the underground newspaper to which Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus both contributed during and after the war. Camus became Combat’s editor and editorial writer between 1944 and 1947. During his tenure, he “was suspicious,” writes Michael McDonald, and he urged his readers to “be suspicious of those who speak the loudest in defense of democratic ideals and absolutes but whose goal is to instill fear in opponents and to silence dissent.”

Camus witnessed and recorded the liberation of France from the Nazi occupation in moving passages like this one:

Paris is firing all its ammunition into the August night. Against a vast backdrop of water and stone, on both sides of a river awash with history, freedom’s barricades are once again being erected. Once again justice must be redeemed with men’s blood.

After the previously unthinkable event that ended the war in the Pacific, the 1945 bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Camus explicitly critiqued the “formidable concert” of opinion impressed with fact that “any average city can be wiped out by a bomb the size of a football.” Against these “eloquent essays,” he wrote darkly,

We can sum it up in one sentence: our technical civilization has just reached its greatest level of savagery. We will have to choose, in the more or less near future, between collective suicide and the intelligent use of our scientific conquests.

Camus heavily documented the early post-war years in France, as the country slowly reconstituted itself, and as coalitions formerly united in resistance collapsed into competing factions. He was alarmed by not only by the fascists on the right, but by the many French socialists seduced by Stalinism. The very next month after the liberation of Paris, Camus began addressing the “problem of government” in an essay titled “To Make Democracy.” Government, writes Camus, “is, to a great extent our problem, as it is indeed the problem of everyone,” but he prefaced his own position with, “we do not believe in politics without clear language.”

By December of 1944, a few months before the fall of Berlin, Camus had grown deeply reflective, expressing attitudes found in many eyewitness accounts. “France has lived through many tragedies,” he wrote, and “will live through many more.” The tragedy of the war, he wrote, was “the tragedy of separation.”

Who would dare speak the word “happiness” in these tortured times? Yet millions today continue to seek happiness. These years have been for them only a prolonged postponement, at the end of which they hope to find that the possibility for happiness has been renewed. Who could blame them? … We entered this war not because of any love of conquest, but to defend a certain notion of happiness. Our desire for happiness was so fierce and pure that it seemed to justify all the years of unhappiness. Let us retain the memory of this happiness and of those who have lost it.

These lucid, passionate essays “include little that is obsolete,” wrote Stanley Hoffman at Foreign Affairs in 2006. “Indeed it is shocking to find how current Camus’ fears, exhortations, and aspirations still are.” Hoffman particularly found Camus’ demand “for morality in politics” compelling. Though “deemed naïve… [by] many other philosophers and writers of his time,” Camus’ insistence on clarity of thought and ethical choice made for what he called “a modest political philosophy… free of all messianic elements and devoid of any nostalgia for an earthly paradise.” How sobering those words sound in our current moment.

Camus’ Combat essays have been collected in Princeton University Press’s Camus at Combat: Writing 1944–1947 and in Between Hell and Reason: Essays from the Resistance Newspaper Combat, 1944–1947 from Wesleyan.

Related Content:

Albert Camus: The Madness of Sincerity — 1997 Documentary Revisits the Philosopher’s Life & Work

Albert Camus Talks About Nihilism & Adapting Dostoyevsky’s The Possessed for the Theatre, 1959

Albert Camus’ Historic Lecture, “The Human Crisis,” Performed by Actor Viggo Mortensen

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness