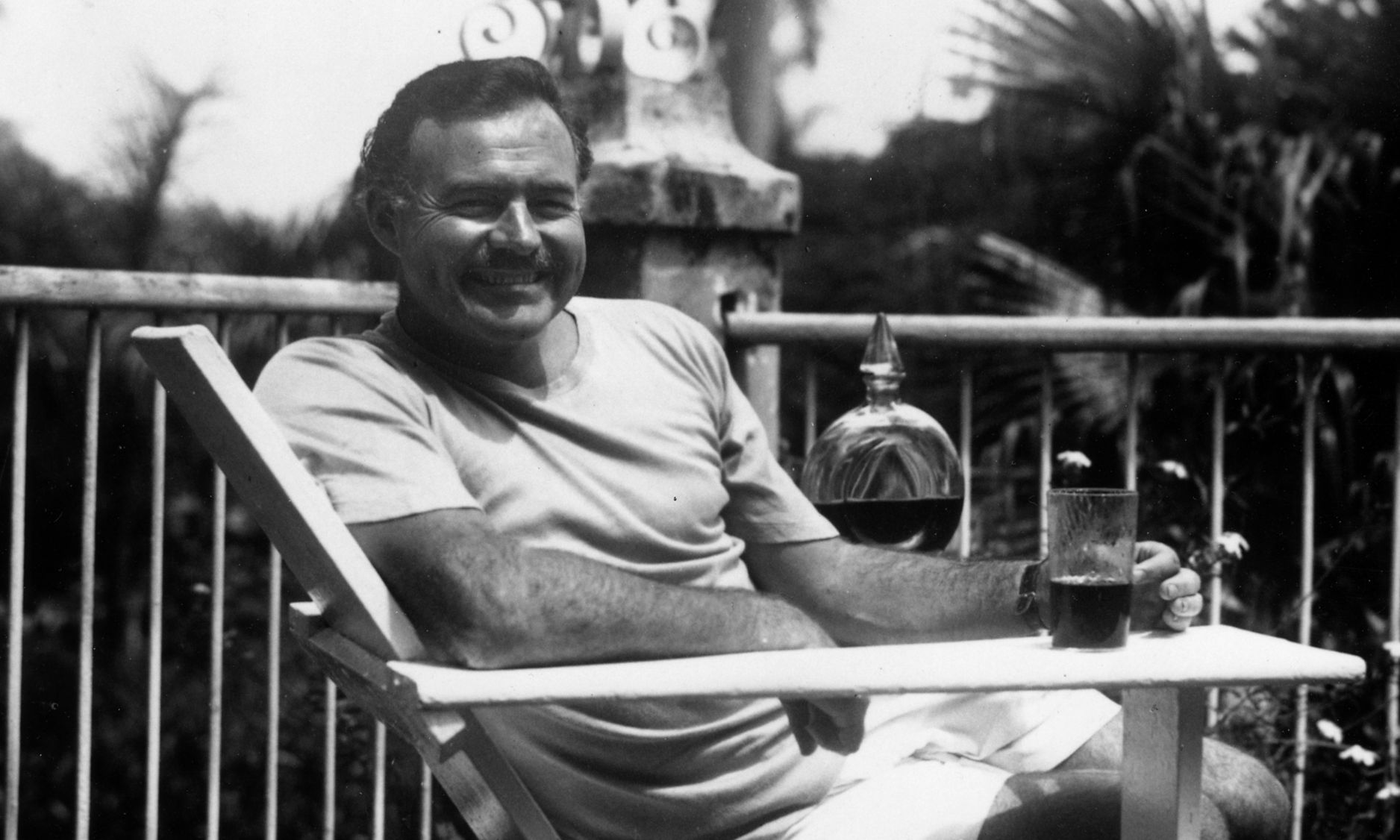

Ernest Hemingway’s romantic adventure of man and marlin, The Old Man and the Sea, has perhaps spent more time on high school freshman English reading lists than any other work of fiction, which might lead one to think of the novel as young adult fiction. But beyond the book’s ability to communicate broad themes of perseverance, courage, and loss, it has an appeal that also reaches old, wizened men like Hemingway’s Santiago and young, imaginative boyish apprentices like his Manolin. The 1952 novella reinvigorated Hemingway’s career, won him a Pulitzer Prize, and eventually contributed to his Nobel win in 1954. And luckily for all those high school English students, Hemingway’s story has lent itself to some worthy screen adaptations, including the 1958 film starring Spencer Tracy as the indefatigable Spanish-Cuban fisherman and a 1990 version with the mighty Anthony Quinn in the role.

One adaptation that readers of Hemingway might miss is the animation above, a co-production with Canadian, Russian, and Japanese studios created by Russian animator Aleksander Petrov. Winner of a 2000 Academy Award for animated short, the film has as much appeal to a range of viewers young and old as Hemingway’s book, and for some of the same reasons—it’s captivatingly vivid depiction of life on the sea, with its long periods of inactivity and short bursts of extreme physical exertion and considerable risk.

Both states provide ample opportunities for complex character development and rich storytelling as well as exciting white-knuckle suspense. Petrov’s film illustrates them all, opening with images of Santiago’s stories of his seafaring boyhood off the coast of Africa and staging the dramatic contests between Santiago, his “brother” the marlin, and the sharks who devour his prize.

But the production here, unlike Hemingway’s spare prose, makes a dazzling display of its technique. For his The Old Man and the Sea, Petrov—only one of a handful of animators skilled in this art—handpainted over 29,000 frames on glass (with help from his son, Dmitri) using slow-drying oils. Petrov moved the paint with his fingers to capture the movement in the next shot, and while the magical effect resembles a moving painting, the shooting itself was very technologically advanced, involving a specially constructed motion-capture camera. Petrov and son began their painting in 1997 and finished two years later, taking to heart some of the lessons of the book, it seems. The film’s creators, however, fared better than The Old Man’s protagonist, richly rewarded for their struggle. In addition to an Oscar, the short won awards from BAFTA, the San Diego Film Festival, and a handful of other prestigious international bodies.

Related Content:

William Faulkner’s Review of Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea (1952)

Watch a Hand-Painted Animation of Dostoevsky’s “The Dream of a Ridiculous Man”

Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Faulkner: A Free Yale Course

The Great Gatsby Is Now in the Public Domain and There’s a New Graphic Novel

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness