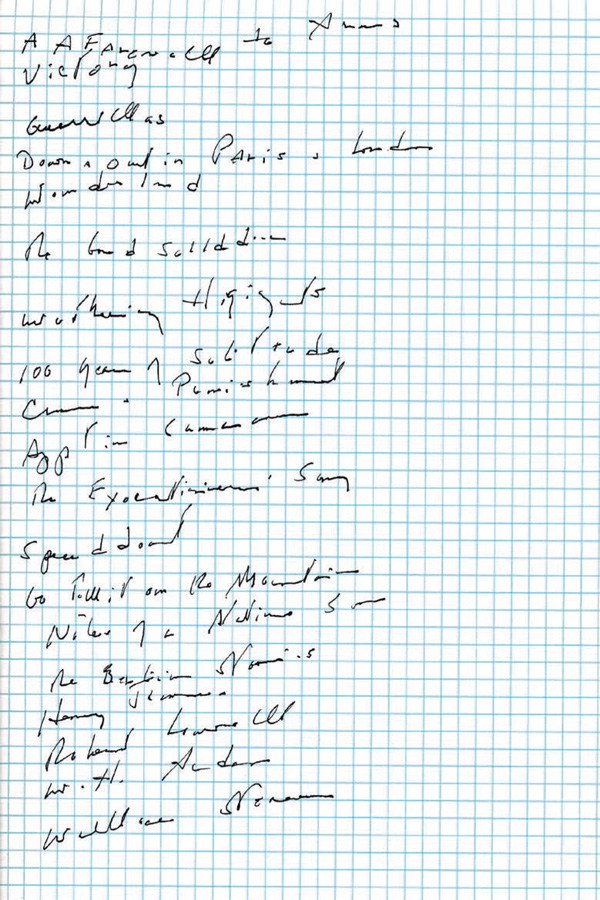

If you’ve read much Joan Didion, you’ve almost surely come across an observation or phrase that has changed the way you look at California, the media, or the culture of the late 20th century — or indeed, changed your life. But if life-changing writers have all had their own lives changed by the writers before them, which writers made Joan Didion the Joan Didion whose writing still exerts an influence today? Conveniently enough, the author of Play It as It Lays, Slouching Towards Bethlehem, and The White Album once drew up a list of the books that changed her life, and it surfaced on Instagram a few years ago:

- A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway

- Victory by Joseph Conrad

- Guerrillas by V.S. Naipaul

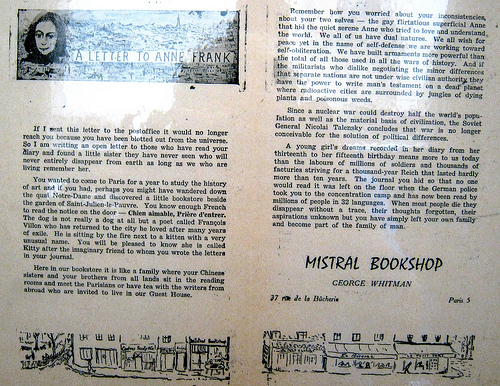

- Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell

- Wonderland by Joyce Carol Oates

- Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

- The Good Soldier by Ford Madox Ford

- One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Márquez

- Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

- Appointment in Samarra by John O’Hara

- The Executioner’s Song by Norman Mailer

- The Novels of Henry James: Washington Square, Portrait of a Lady, The Bostonians, Wings of the Dove, The Ambassadors, The Golden Bowl, Daisy Miller, The Aspern Papers, The Turn of the Screw

- Speedboat by Renata Adler

- Go Tell It on the Mountain by James Baldwin

- Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin

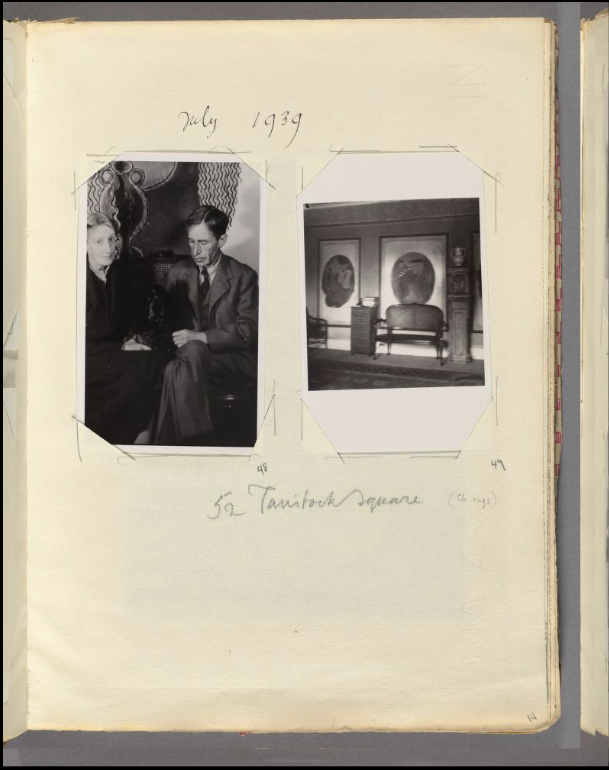

- The Berlin Stories by Christopher Isherwood

- Collected Poems by Robert Lowell

- Collected Poems by W.H. Auden

- The Collected Poems by Wallace Stevens

In 1978, when Didion had already become a new-journalism icon, The Paris Review’s Linda Kuehl asked her whether any writer influenced her more than others. “I always say Hemingway,” she replied, “because he taught me how sentences worked. When I was fifteen or sixteen I would type out his stories to learn how the sentences worked. I taught myself to type at the same time.” Teaching A Farewell to Arms, her number-one most influential book, she “fell right back into those sentences. I mean they’re perfect sentences. Very direct sentences, smooth rivers, clear water over granite, no sinkholes.”

Didion’s list also includes other masters of the sentence, albeit most of them possessed of sensibilities quite distinct from Hemingway’s. Henry James, for instance: “He wrote perfect sentences, too, but very indirect, very complicated. Sentences with sinkholes. You could drown in them.” Consider them alongside the other writers among her favored nineteen, from novelists like Emily Brontë and Joyce Carol Oates to poets like Wallace Stevens and W.H. Auden to figures with one foot in literature and the other in journalism like George Orwell and Norman Mailer, and you’ve got a mix that no two aspiring writers could read and come out sounding exactly alike. No surprise that such a set of influences would produce a writer like Didion, so often imitated but, in her niche, never equaled.

Related Content:

Read 12 Masterful Essays by Joan Didion for Free Online, Spanning Her Career From 1965 to 2013

Joan Didion Reads From New Memoir, Blue Nights, in Short Film Directed by Griffin Dunne

New Documentary Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold Now Streaming on Netflix

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.