There may be no sweeter sound to the ears of Open Culture writers than the words “public domain”—you might even go so far as to call it our “cellar door.” The phrase may not be as musical, but the fact that many of the world’s cultural treasures cannot be copyrighted in perpetuity means that we can continue to do what we love: curating the best of those treasures for readers as they appear online. Public domain means companies can sell those works without incurring any costs, but it also means that anyone can give them away for free. “Anyone can re-publish” public domain works, notes Lifehacker, “or chop them up and use them in other projects.” And thereby emerges the remixing and repurposing of old artifacts into new ones, which will themselves enter the public domain of future generations.

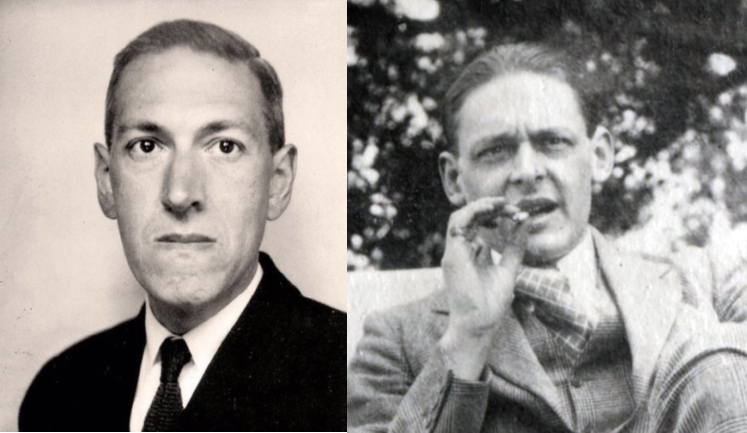

Some of those future works of art may even become the next Great American Novel, if such a thing still exists as anything more than a hackneyed cliché. Of course, no one seriously goes around saying they’re writing the “Great American Novel,” unless they’re Philip Roth in the 70s or William Carlos Williams (top right) in the 20s, who both somehow pulled off using the phrase as a title (though Roth’s book doesn’t quite live up to it.) Where Roth casually used the concept in a light novel about baseball, Williams’ The Great American Novel approached it with deep concern for the survival of the form itself. His modernist text “engages the techniques of what we would now call metafiction,” writes literary scholar April Boone, “to parody worn out formulas and content and, ironically, to create a new type of novel that anticipates postmodern fiction.”

We will all, as of January 1, 2019, have free, unfettered access to Williams’ metafictional shake-up of the formulaic status quo, when “hundreds of thousands of… books, musical scores, and films first published in the United States during 1923” enter the public domain, as Glenn Fleishman writes at The Atlantic. Because of the complicated history of U.S. copyright law—especially the 1998 “Sonny Bono Act” that successfully extended a copyright law from 50 to 70 years (for the sake, it’s said, of Mickey Mouse)—it has been twenty years since such a massive trove of material has become available all at once. But now, and “for several decades from 2019 onward,” Fleishman points out, “each New Year’s Day will unleash a full year’s worth of works published 95 years earlier.”

In other words, it’ll be Christmas all over again in January every year, and while you can browse the publication dates of your favorite works yourself to see what’s coming available in coming years, you’ll find at The Atlantic a short list of literary works included in next-year’s mass-release, including books by Aldous Huxley, Winston Churchill, Carl Sandburg, Edith Wharton, and P.G. Wodehouse. Lifehacker has several more extensive lists, which we excerpt below:

Movies [see many more at Indiewire]

All these movies, including:

- Cecil B. DeMille’s (first, less famous, silent version of) The Ten Commandments

- Harold Lloyd’s Safety Last!, including that scene where he dangles off a clock tower, and his Why Worry?

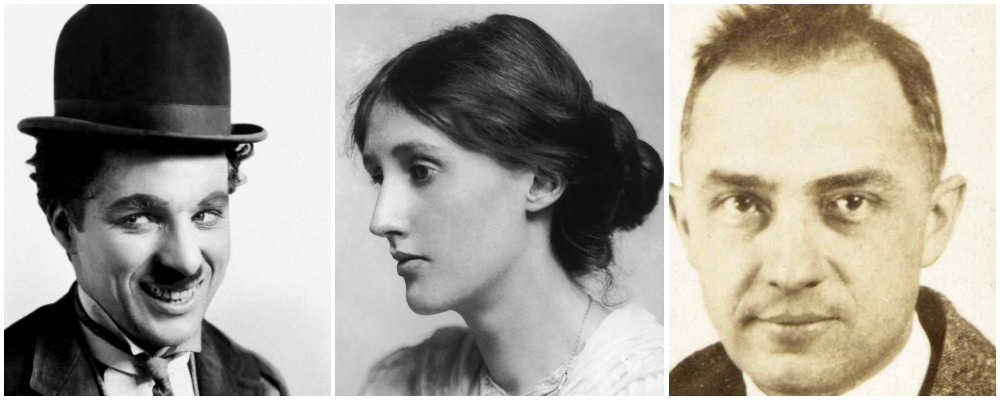

- A long line-up of feature-length silent films, including Buster Keaton’s Our Hospitalityand Charlie Chaplin’s The Pilgrim

- Short films by Chaplin, Keaton, Laurel and Hardy, and Our Gang (later Little Rascals)

- Cartoons including Felix the Cat(the character first appeared in a 1919 cartoon)

- Marlene Dietrich’s film debut, a bit part in the German silent comedy The Little Napoleon; also the debuts of Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and Fay Wray

Music

All this music, including these classics:

- “King Porter Stomp”

- “Who’s Sorry Now?”

- “Tin Roof Blues”

- “That Old Gang of Mine”

- “Yes! We Have No Bananas”

- “I Cried for You”

- “The Charleston”—written to accompany, and a big factor in the popularity of, the Charleston dance

- Igor Stravinsky’s “Octet for Wind Instruments”

Literature

All these books, and these books, including the classics:

- Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

- Cane by Jean Toomer

- The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran

- The Ego and the Id by Sigmund Freud

- Towards a New Architecture by Le Corbusier

- Whose Body?, the first Lord Peter Wimsey novel by Dorothy L. Sayers

- Two of Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot novels, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and The Murder on the Links

- The Prisoner, volume 5 of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (note that English translations have their own copyrights)

- The Complete Works of Anthony Trollope

- George Bernard Shaw’s play Saint Joan

- Short stories by Christie, Virginia Woolf, H.P. Lovecraft, Katherine Mansfield, and Ernest Hemingway

- Poetry by Edna St. Vincent Millay, E.E. Cummings, William Carlos Williams, Rainer Maria Rilke, Wallace Stevens, Robert Frost, Sukumar Ray, and Pablo Neruda

- Works by Jane Austen, D.H. Lawrence, Edith Wharton, Jorge Luis Borges, Mikhail Bulgakov, Jean Cocteau, Italo Svevo, Aldous Huxley, Winston Churchill, G.K. Chesterton, Maria Montessori, Lu Xun, Joseph Conrad, Zane Grey, H.G. Wells, and Edgar Rice Burroughs

Art

These artworks, including:

- Constantin Brâncuși’s Bird in Space

- Henri Matisse’s Odalisque With Raised Arms

- Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass)

- Yokoyama Taikan’s Metempsychosis

- Work by M. C. Escher, Pablo Picasso, Wassily Kandinsky, Max Ernst, and Man Ray

Again, these are only partial lists of highlights, and such highlights…. Speaking for myself, I cannot wait for free access to the very best (and even worst, and weirdest, and who-knows-what-else) of 1923. And of 1924 in 2020, and 1925 and 2021, and so on and so on….

via The Atlantic

Related Content:

The Public Domain Project Makes 10,000 Film Clips, 64,000 Images & 100s of Audio Files Free to Use

List of Great Public Domain Films

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness