The light was departing. The brown air drew down

all the earth’s creatures, calling them to rest

from their day-roving, as I, one man alone,prepared myself to face the double war

of the journey and the pity, which memory

shall here set down, nor hesitate, nor err.

Reading Dante’s Inferno, and Divine Comedy generally, can seem a daunting task, what with the book’s wealth of allusion to 14th century Florentine politics and medieval Catholic theology. Much depends upon a good translation. Maybe it’s fitting that the proverb about translators as traitors comes from Italian. The first Dante that came my way—the unabridged Carlyle-Okey-Wicksteed English translation—renders the poet’s terza rima in leaden prose, which may well be a literary betrayal.

Gone is the rhyme scheme, self-contained stanzas, and poetic compression, replaced by wordiness, antiquated diction, and needless density. I labored through the text and did not much enjoy it. I’m far from an expert by any stretch, but was much relieved to later discover John Ciardi’s more faithful English rendering, which immediately impresses upon the senses and the memory, as in the description above in the first stanzas of Canto II.

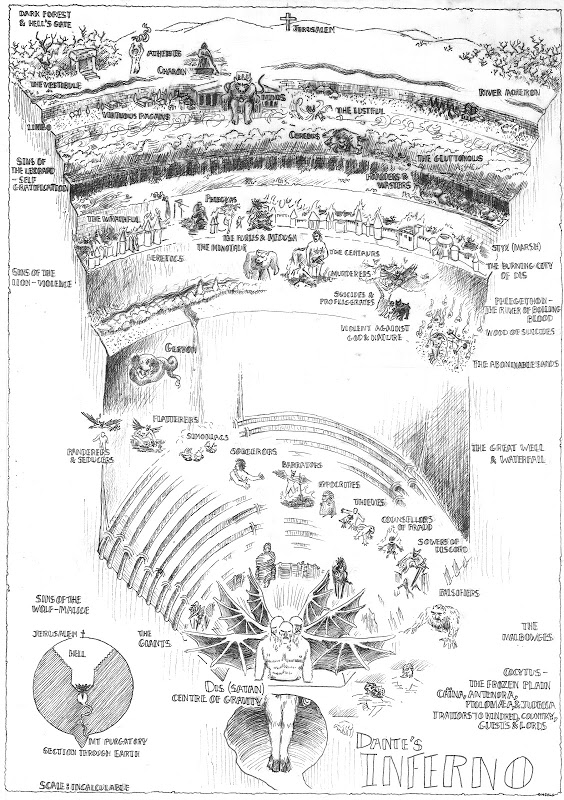

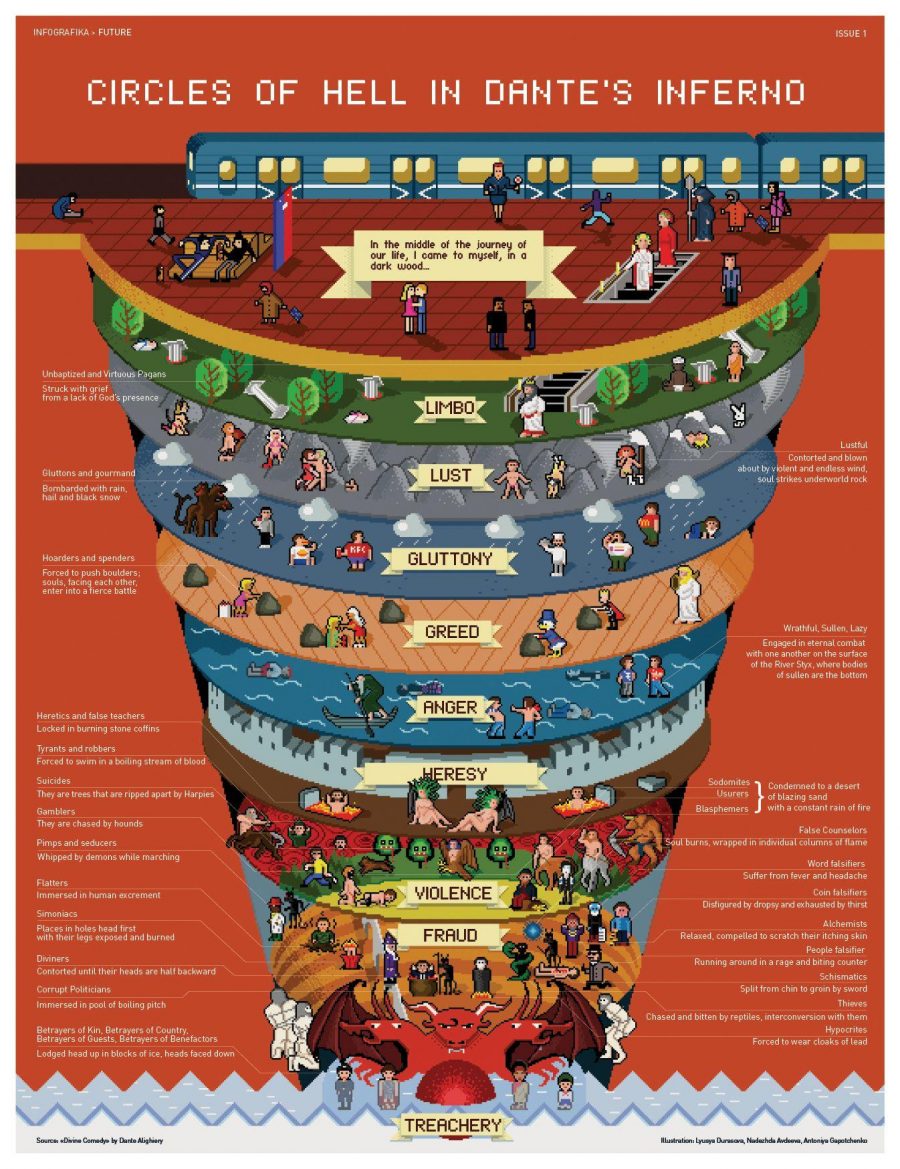

The sole advantage, perhaps, of the translation I first encountered lies in its use of illustrations, maps, and diagrams. While readers can follow the poem’s vivid action without visual aids, these lend to the text a kind of imaginative materiality: saying yes, of course, this is a real place—see, it’s right here! We can suspend our disbelief, perhaps, in Catholic doctrine and, doubly, in Dante’s weirdly officious, comically bureaucratic, scheme of hell.

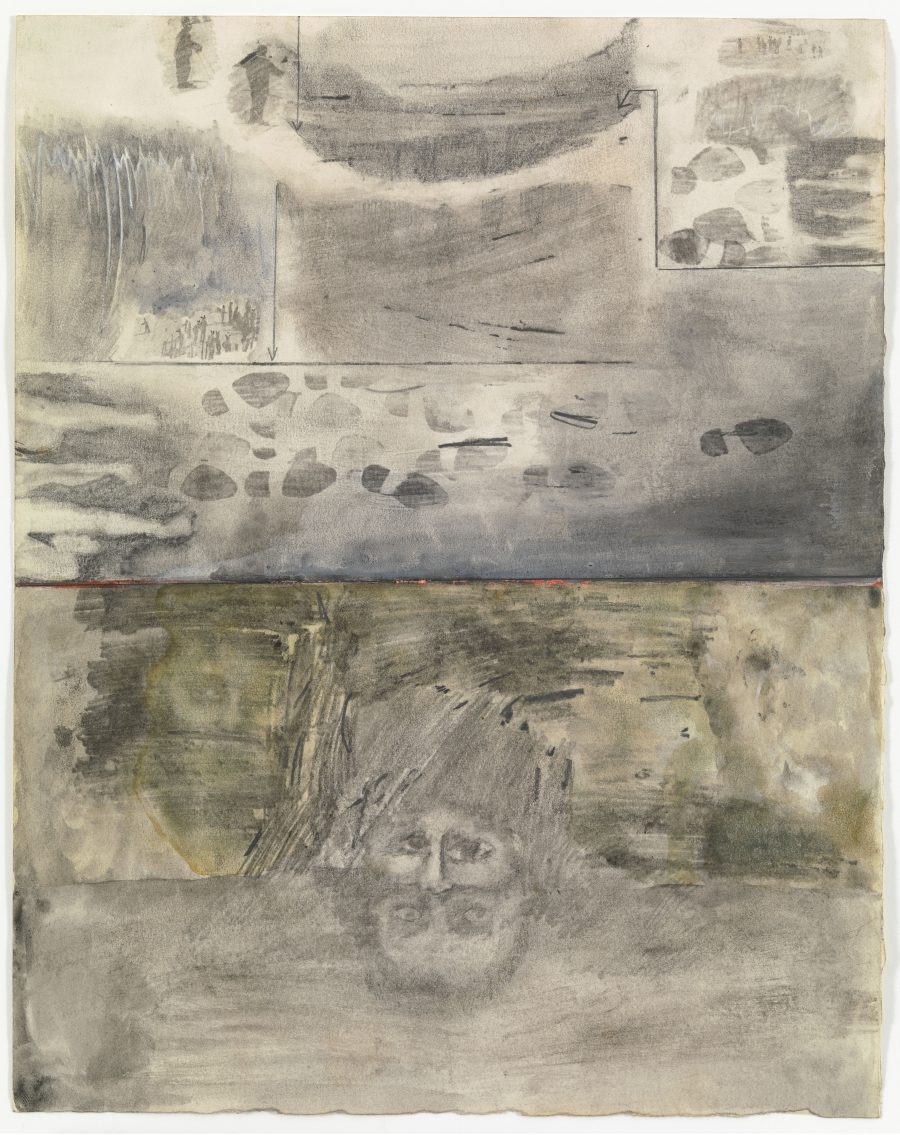

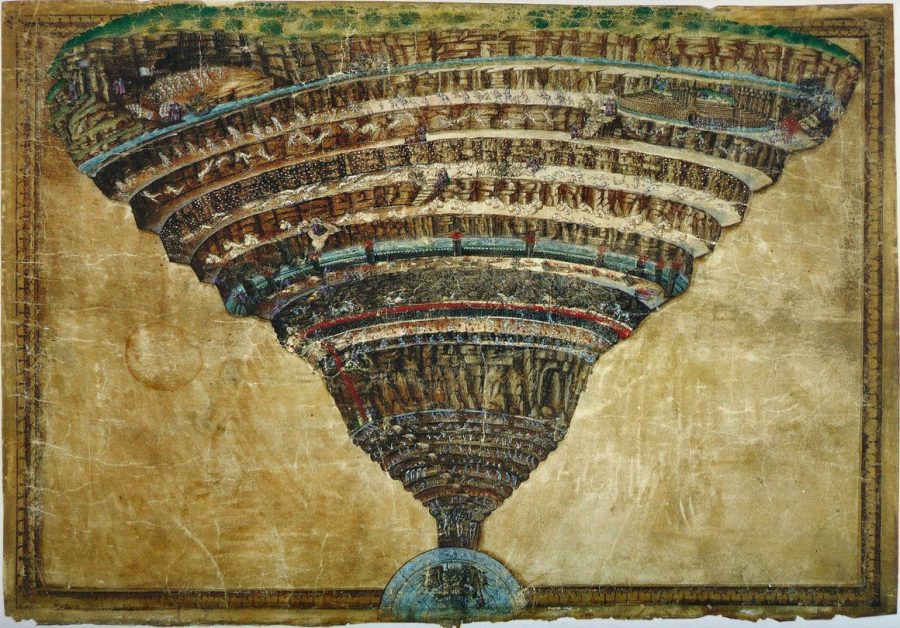

Indeed, readers of Dante have been inspired to map his Inferno for almost as long as they have been inspired to translate it into other languages—and we might consider these maps more-or-less-faithful visual translations of the Inferno’s descriptions. One of the first maps of Dante’s hell (top) appeared in Sandro Botticelli’s series of ninety illustrations, which the Renaissance great and fellow Florentine made on commission for Lorenzo de’Medici in the 1480s and 90s.

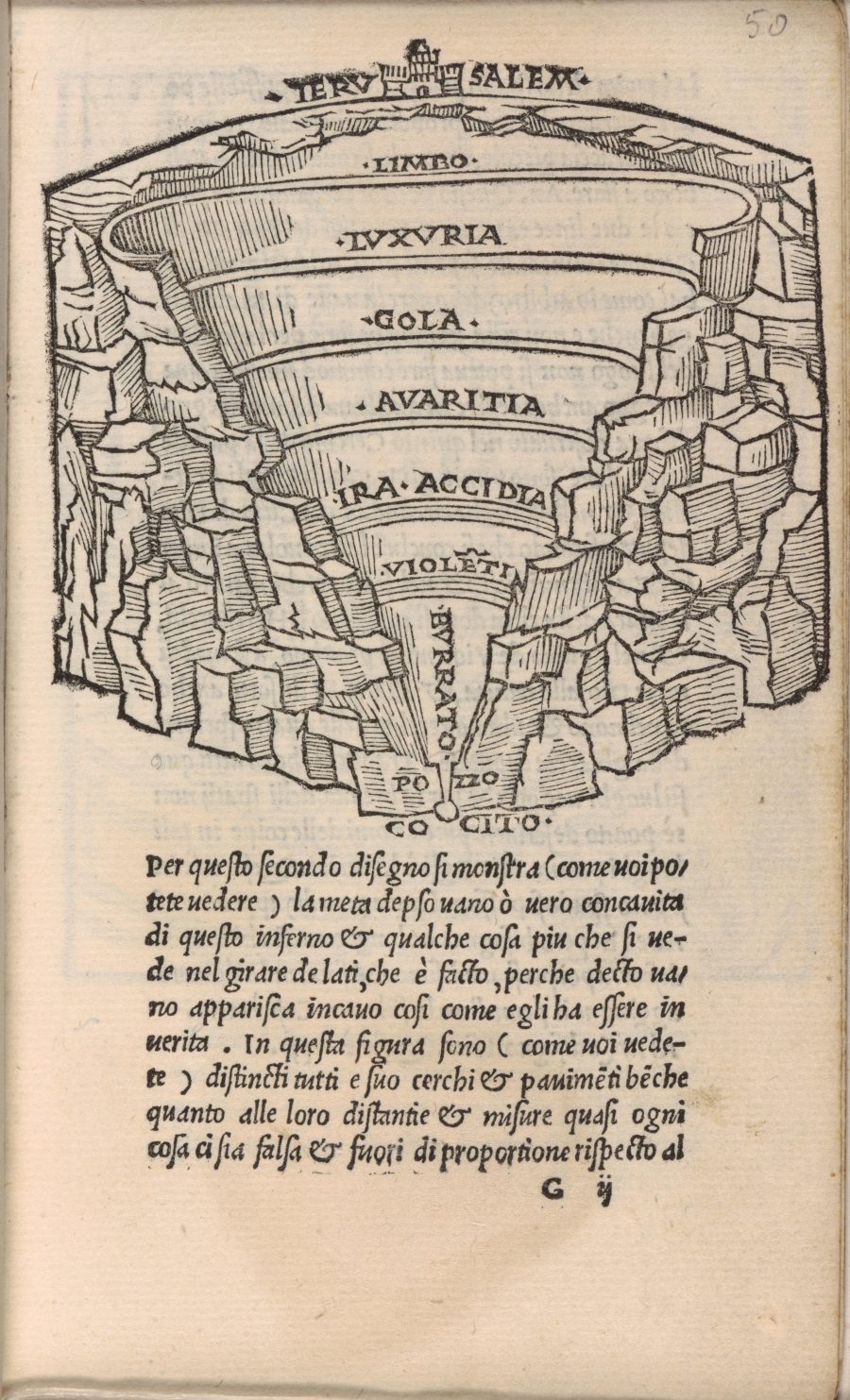

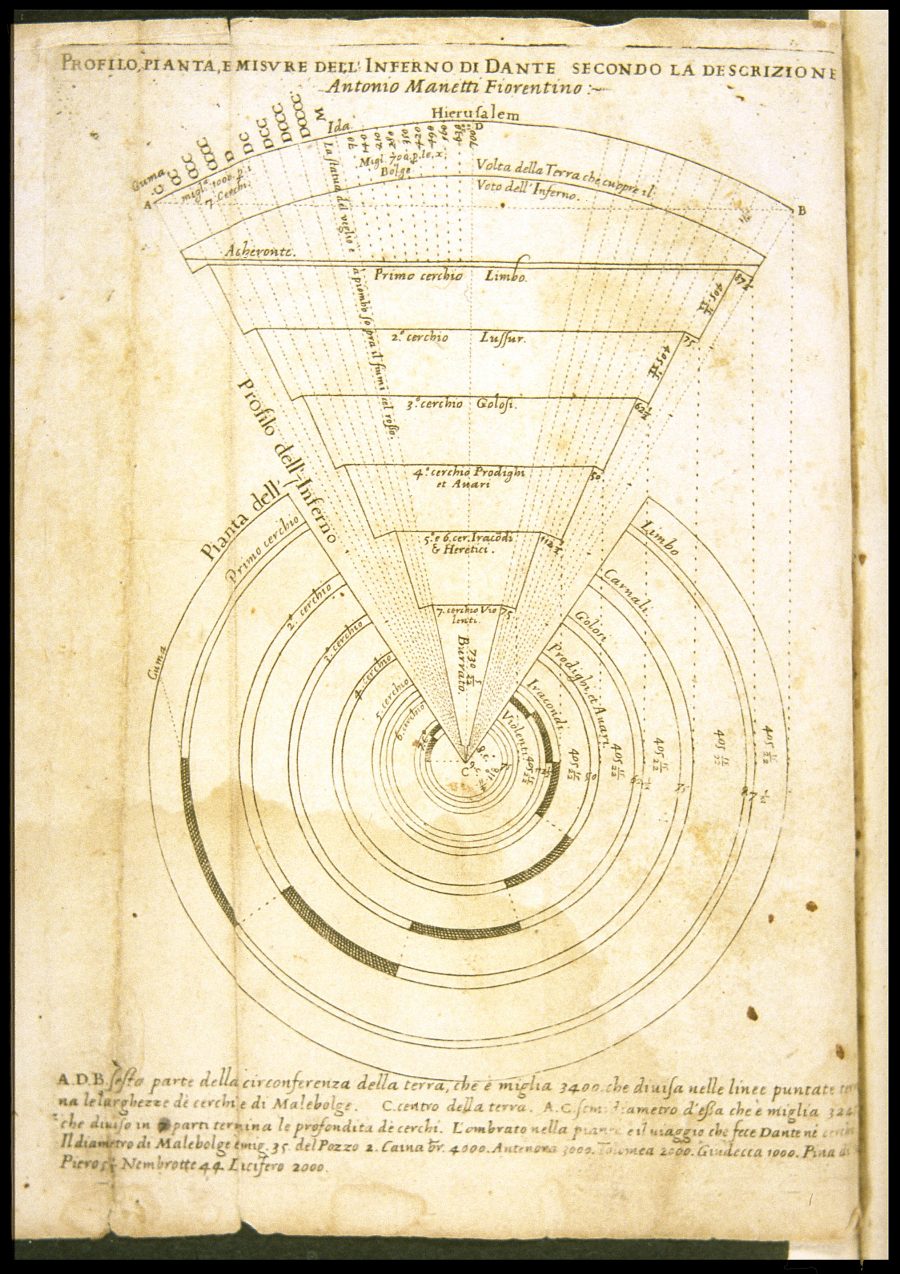

Botticelli’s “Chart of Hell,” writes Deborah Parker, “has long been lauded as one of the most compelling visual representations… a panoptic display of the descent made by Dante and Virgil through the ‘abysmal valley of pain.’” Below it, we see one of Antonio Manetti’s 1506 woodcut illustrations, a series of cross-sections and detailed views. Maps continued to proliferate: see printmaker Antonio Maretti’s 1529 diagram further up, Joannes Stradanus’ 1587 version, above, and, below, a 1612 illustration below by Jacques Callot.

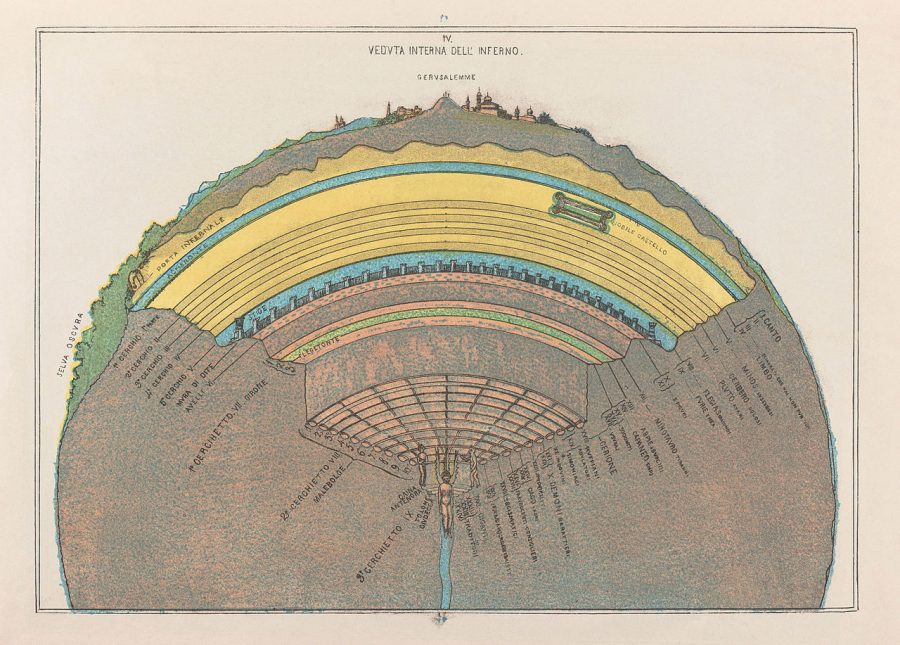

Dante’s hell lends itself to any number of visual treatments, from the purely schematic to the broadly imaginative and interpretive. Michelangelo Caetani’s 1855 cross-section chart, below, lacks the illustrative detail of other maps, but its use of color and highly organized labeling system makes it far more legible that Callot’s beautiful but busy drawing above.

Though we are within our rights as readers to see Dante’s hell as purely metaphorical, there are historical reasons beyond religious belief for why more literal maps became popular in the 15th century, “including,” writes Atlas Obscura, “the general popularity of cartography at the time and the Renaissance obsession with proportions and measurement.”

Even after hundreds of years of cultural shifts and upheavals, the Inferno and its humorous and horrific scenes of torture still retain a fascination for modern readers and for illustrators like Daniel Heald, whose 1994 map, above, while lacking Botticelli’s gilded brilliance, presents us with a clear visual guide through that perplexing valley of pain, which remains—in the right translation or, doubtless, in its original language—a pleasure for readers who are willing to descend into its circular depths. Or, short of that, we can take a digital train and escalators into an 8‑bit video game version.

See more maps of Dante’s Inferno here, here, and here.

via Atlas Obscura

Related Content:

A Free Course on Dante’s Divine Comedy from Yale University

Hear Dante’s Inferno Read Aloud by Influential Poet & Translator John Ciardi (1954)

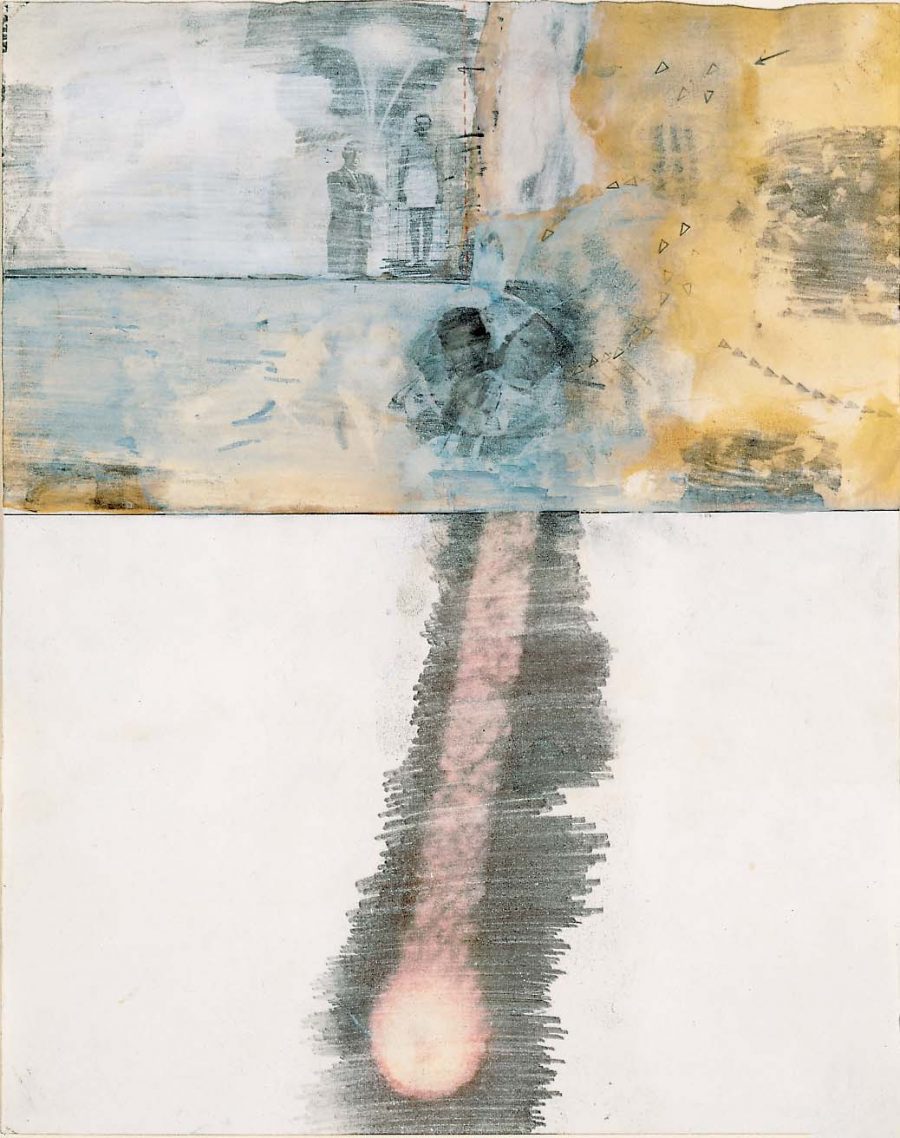

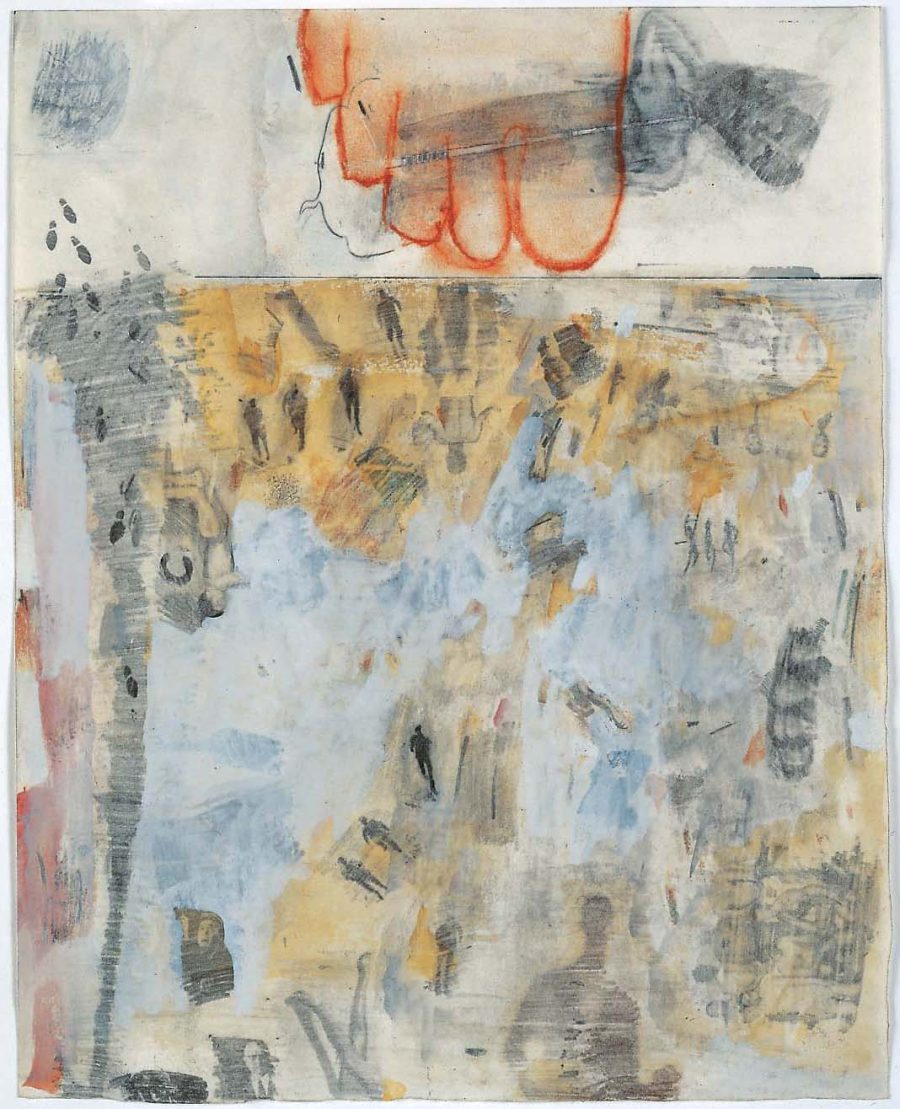

Robert Rauschenberg’s 34 Illustrations of Dante’s Inferno (1958–60)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness