You can lead the I‑generation to a bookstore, but can you make them read?

Perhaps, especially if the volume has an eye-catching cover image that bleeds off the edge.

If nothing else, they can be enlisted to provide some stunning free publicity for the titles that appeal to their highly visual sense of creative play. (An author’s dream!)

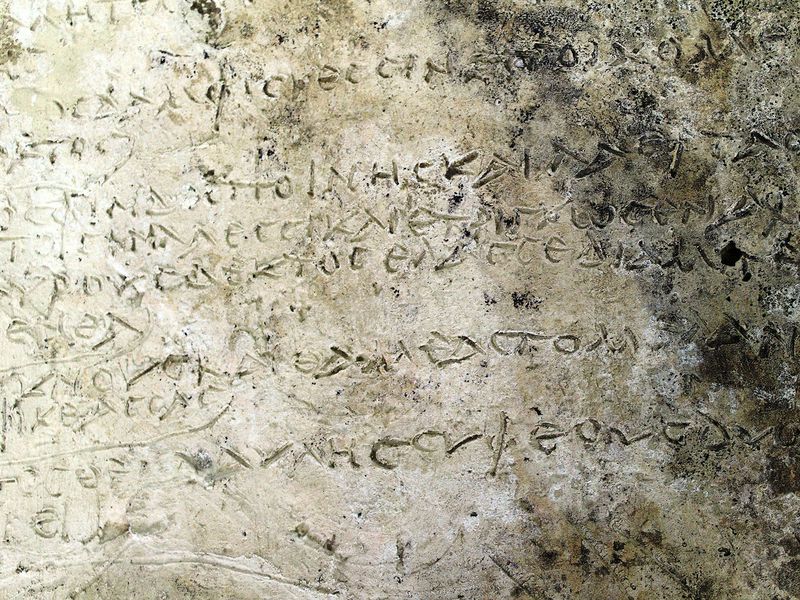

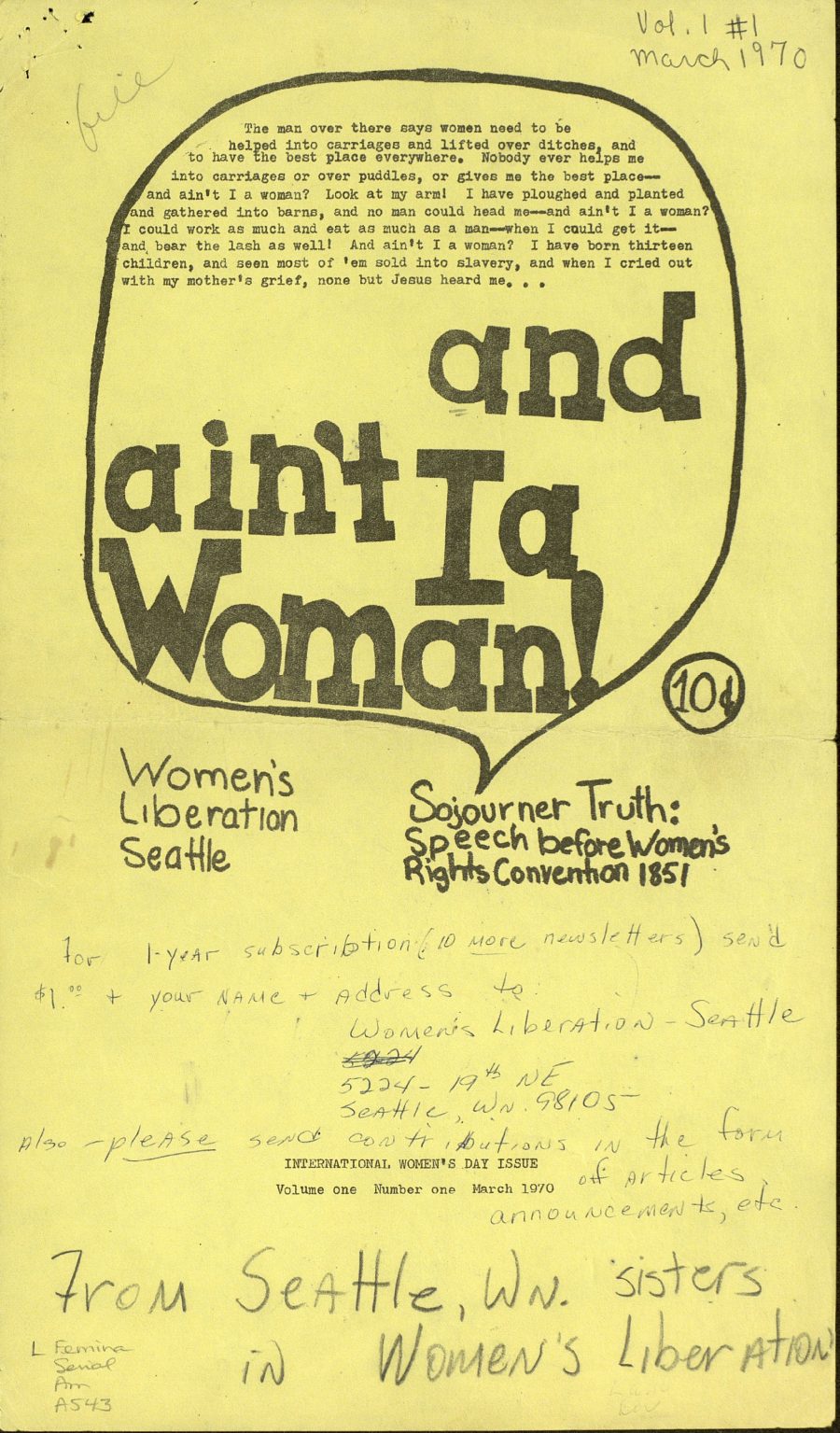

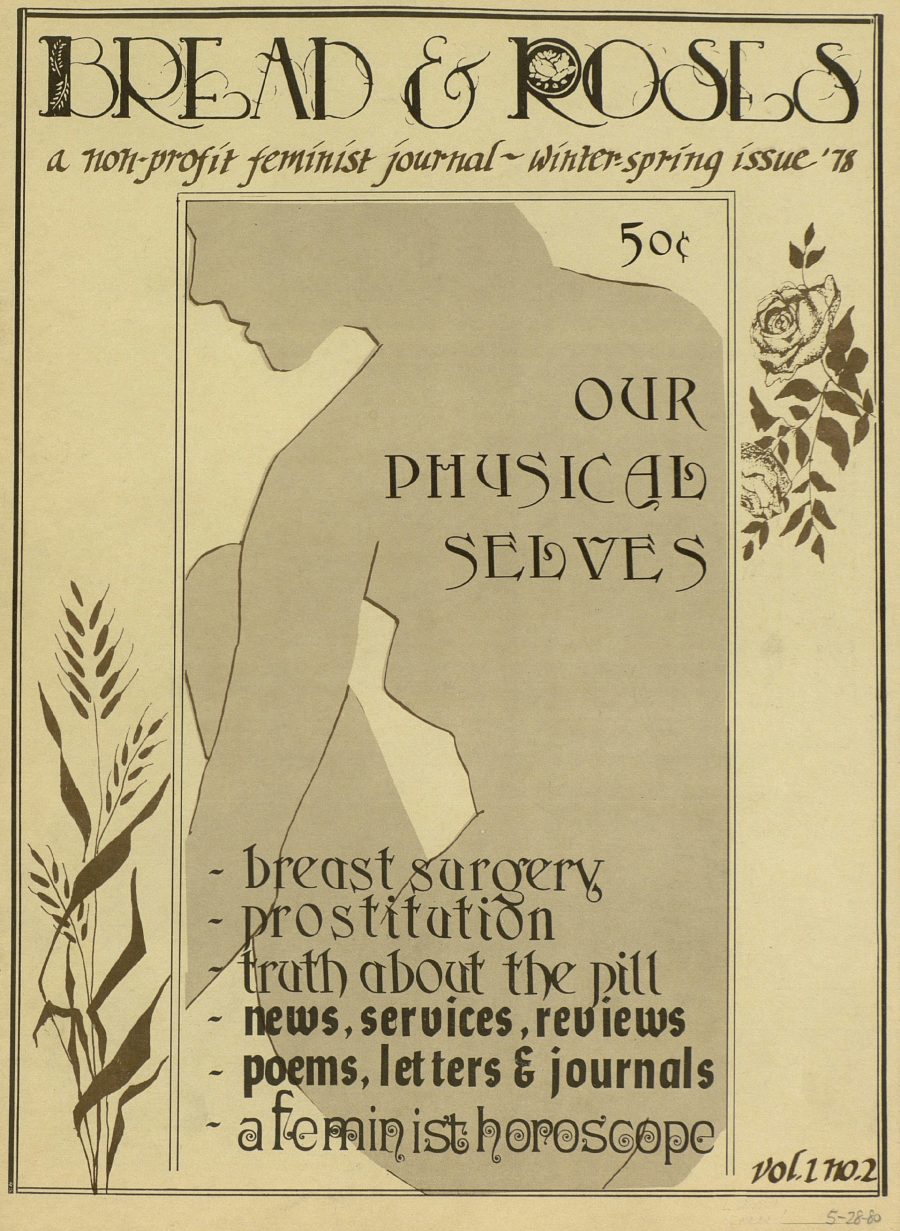

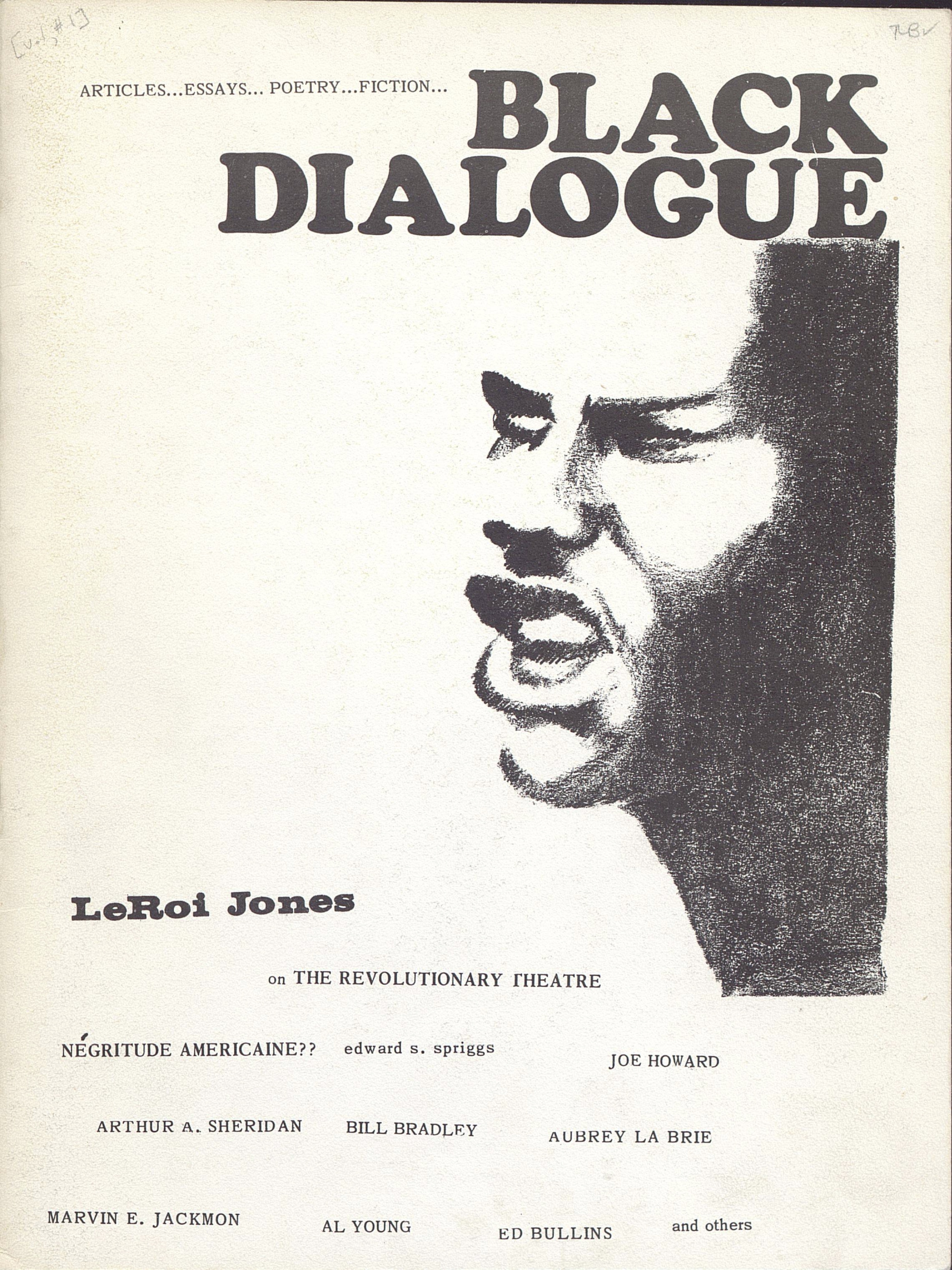

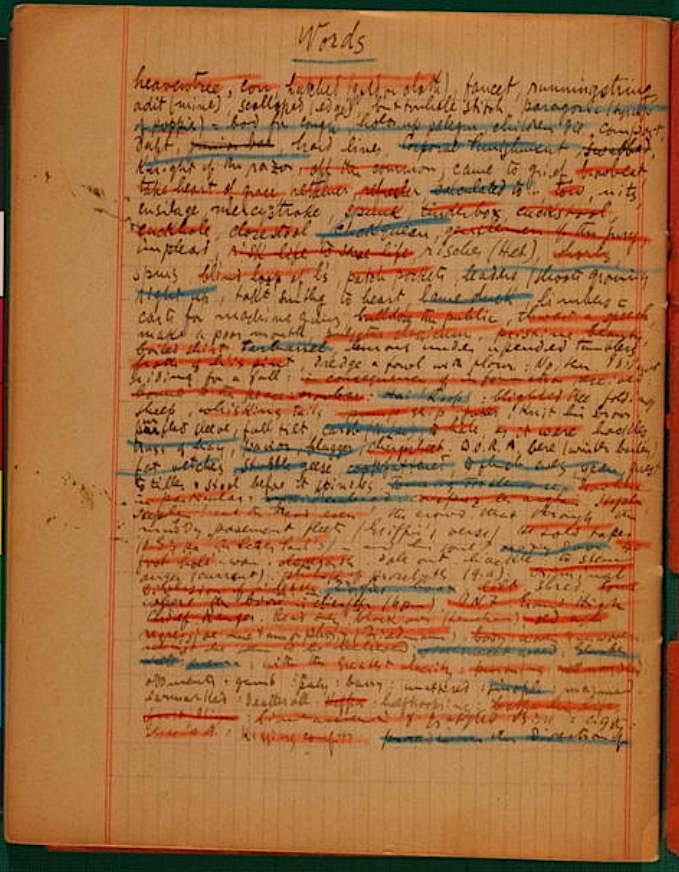

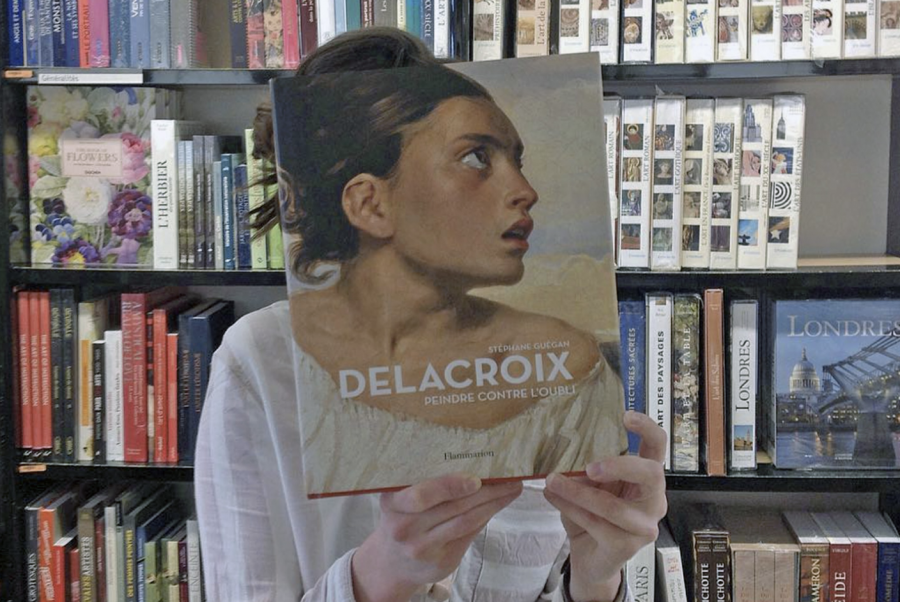

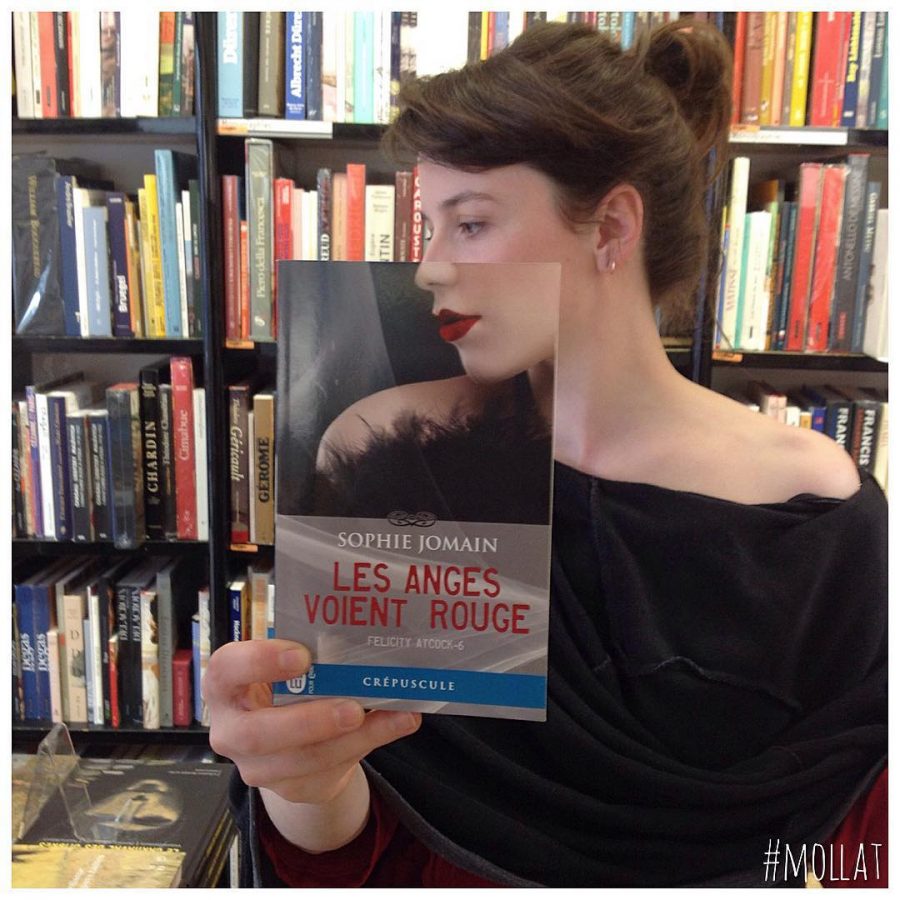

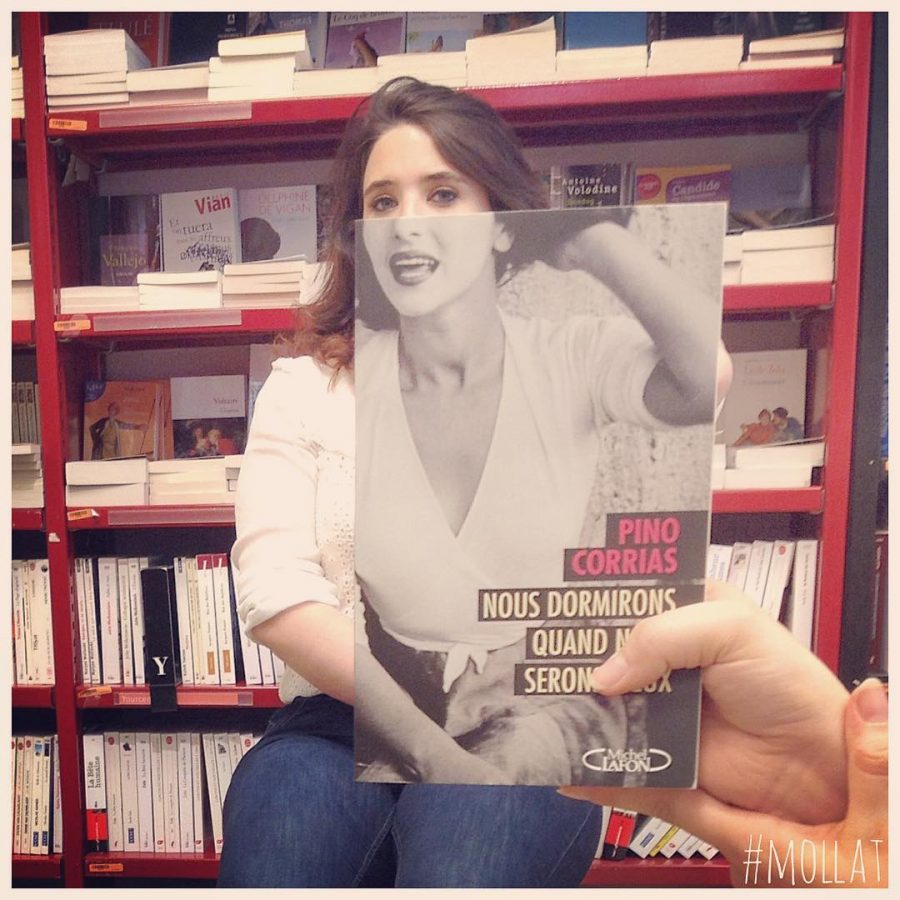

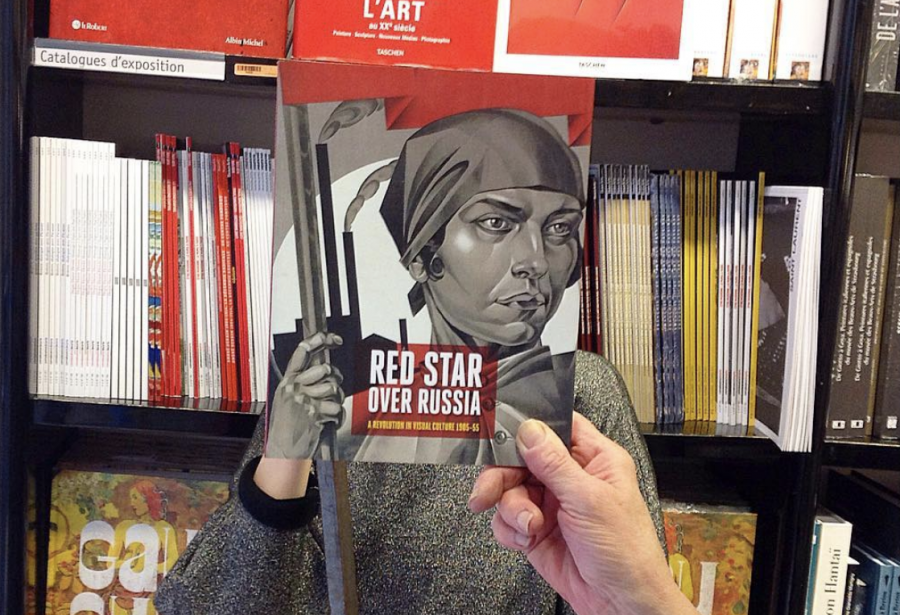

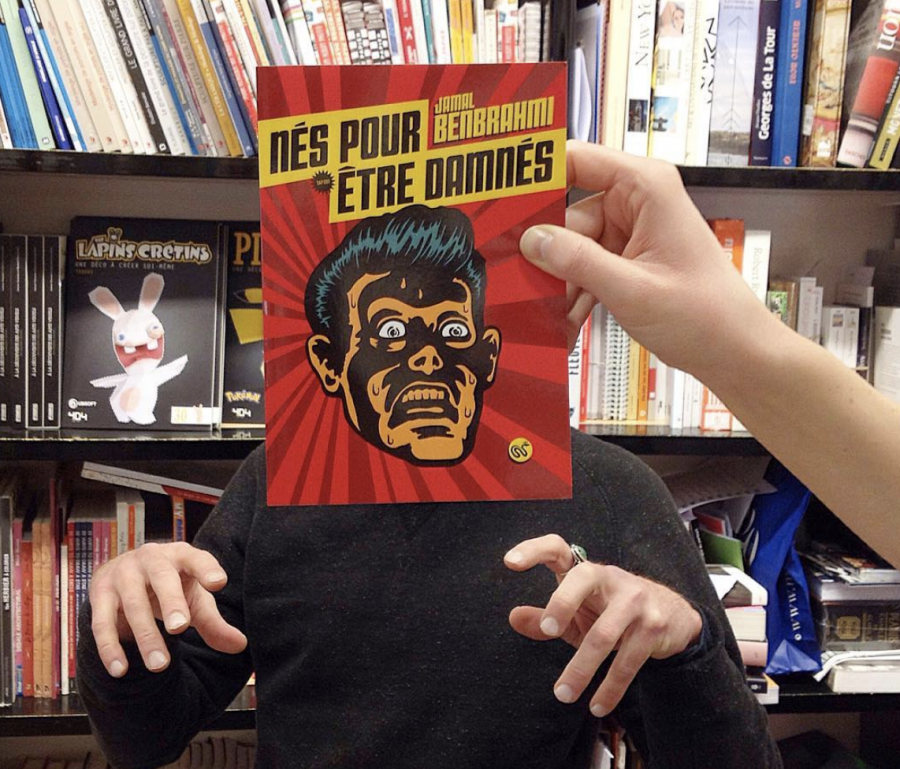

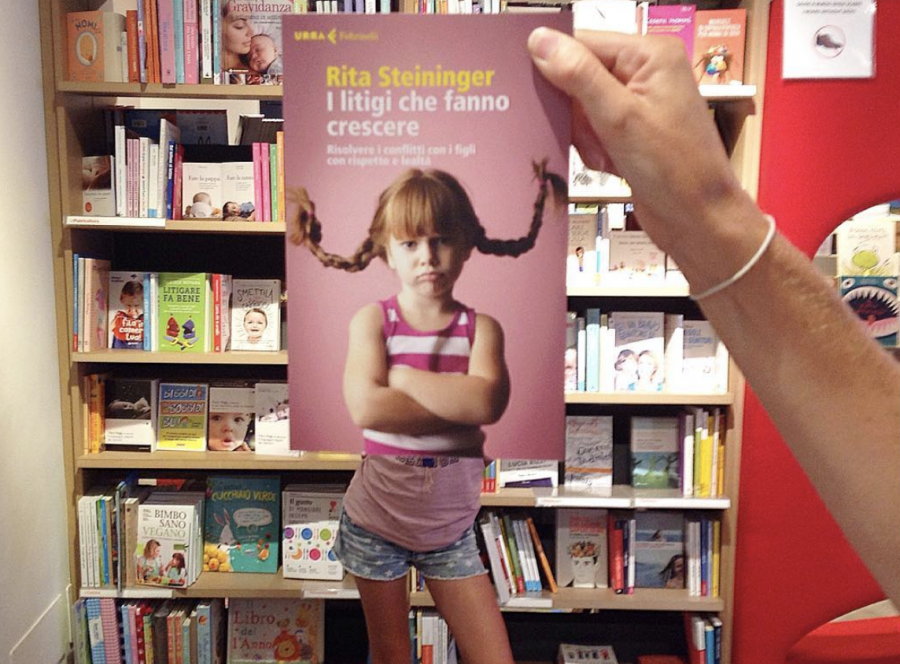

France’s first indie bookstore, Bordeaux’s Librairie Mollat, is reeling ‘em in with Book Face, an irresistible selfie challenge that harkens back to DJ Carl Morris’ Sleeveface project, in which one or more people are photographed “obscuring or augmenting any part of their body or bodies with record sleeve(s), causing an illusion.”

The results are proliferating on the store’s Instagram, as fetching young things (and others) apply themselves to finding the best angles and costumes for their lit-based Trompe‑l’œil masterstrokes.

…even the ones that don’t quite pass the forced perspective test have the capacity to charm.

…and not every shot requires intense pre-production and precision placement.

Hopefully, we’ll see more kids getting into the act soon. In fact, if some youngsters of your acquaintance are expressing a bit of boredom with their vacances d’été, try turning them loose in your local bookstore to identify a likely candidate for a Book Face of their own.

(Remember to support the bookseller with a purchase!)

Back stateside, some librarians shared their pro tips for achieving Book Face success in this 2015 New York Times article. The New York Public Library’s Morgan Holzer also cites Sleeveface as the inspiration behind #BookfaceFriday, the hashtag she coined in hopes that other libraries would follow suit.

With over 50,000 tagged posts on Instagram, looks like it’s caught on!

See Librairie Mollat’s patrons’ gallery of Book Faces here.

Readers, if you’ve Book Faced anywhere in the world, please share the link to your efforts in the comments section.

via This is Colossal/Hyperallergic

Related Content:

The Art of Sci-Fi Book Covers: From the Fantastical 1920s to the Psychedelic 1960s & Beyond

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. In honor of her son’s 18th birthday, she invites you to Book Face your baby using The Big Rumpus, her first book, for which he served as cover model. Follow her @AyunHalliday.